Building on the theme of singing parrots from the eighth verse of the Śrī Veṅkaṭeśa Suprabhātam, this week’s verse gets even more musical:

tantrī-prakarṣa-madhura-svanayā vipañcyā gāyaty ananta-caritaṃ tava Nārado ’pi | bhāṣā-samagram asakṛt-kara-cāra-ramyaṃ Śeṣâdri-śekhara-vibho! tava suprabhātam || (VSu 9) तन्त्री-प्रकर्ष-मधुर-स्वनया विपञ्च्या गायत्य् अनन्त-चरितं तव नारदो ऽपि । भाषा-समग्रम् असकृत्-कर-चार-रम्यं शेषाद्रि-शेखर-विभो ! तव सुप्रभातम् ॥

Accompanied by his veena, its sweet sounds produced by pulling and plucking its strings, Even Nārada sings Your unending glory in the fullness of the vernacular, made even more charming by his constantly-moving hands: O all-pervading Almighty atop Seshadri, a blessed morning unto You!

The language(s) of devotion

One of the hidden beauties of this verse is the word bhāṣā “language”. While the word is used these days to simply mean any language, in Sanskrit it is often used when referring to a vernacular language (the “language of the people”, so to speak). We see this, for instance, in Pāṇini’s Aṣṭâdhyāyī grammar, where the word (usually in the form bhāṣāyām) often refers to forms that are more colloquial.

In this context, we can interpret bhāṣā to refer most likely to the Tamil language, and specifically to the 4000 Divya Prabandham of the Tamil Āzhvārs. This suggests, quite intriguingly, that Nārada himself is singing the Tamil Prabandham in which the Āzhvārs sing the unending glory of the Supreme Lord.1

Of course, Telugu speakers would also be fully justified in seeing the word bhāṣā as being a reference perhaps to Taḷḷapāka Annamācārya’s beautiful devotional songs dedicated to Lord Śrīnivāsa! The truth is that the Divine’s glory is so endless that all the languages of earth would still fail to capture Him completely. As the Taittirīya Upaniṣad’s Brahmānanda-vallī says, the Lord is yato vāco nivartante “that of which all words fall short”.

But in this very transcendence (paratva) of the Divine lies, paradoxically, His supreme accessibility (saulabhya): He can be sung to in any human language, by any human voice, wherever and whenever.

On strings and waves

There is a subtle play on words in the beginning of this verse, tantrī-prakarṣa:

The literal meaning of the word tantrī is “string”, in reference to the strings of Nārada’s veena. We can, however, also connect it to the Sāṅkhya concept of guṇa which also literally means “string”, in this case the very threads out of which the fabric of reality is woven.

The word prakarṣa can literally mean “plucking” or “pulling”, but it also has the meaning of “best, superlative”.

Putting these two pieces together, we see that tantrī-prakarṣa does not simply mean “plucking the strings [of the veena]”, but also can mean “best of the guṇas”. This is a reference to the Śrīvaiṣṇava modification of Sāṅkhya ontology, which includes a pure, unadulterated strand of sattva alone (śuddha-sattva, “pure sattva”) which is the material for all purely spiritual entities.

The esoteric suggestion is that the melodies of Nārada’s veena and the words he sings are all due to this divinely-originated, pure, śuddha-sattva which is the spiritual material that constitutes the manifestations of the Divine. Or to put it differently: manifestations of the Divine sing, using manifestations of the Divine, songs in praise of the Divine which are themselves manifestations of the Divine!

A single-string melody

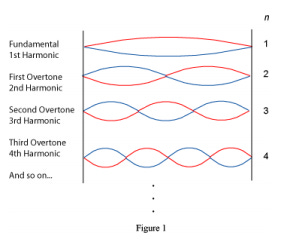

I also hear in this second interpretation of the phrase tantrī-prakarṣa the famous opening phrase of the Gītā-Bhāṣya of Swāmī Rāmānuja, in which he calls the Lord nikhila-heya-pratyanīka-kalyāṇa-eka-tāna. This phrase is usually translated as “wholly intent upon wellbeing utterly opposed to everything reprehensible”, but its closing component eka-tāna actually literally means “single string”. Just as an instrument with a single string plays a single fundamental note (with higher-order overtones), so too is the Lord’s singular and fundamental concern our wellbeing (while factoring in an infinity of higher-order terms that we might not grasp).

And of course this phrase also connects to the concept of śuddha-sattva, as it is also a single string of goodness, purified of everything reprehensible from the other two strings of passion and of inertia.

Fingers dancing on the fretboard

One final note (if you will excuse the musical pun!) The word asakrt-kara-cāra-ramyam can mean two things, depending on whether we treat it as an adverb or an adjective:

[As an adverb] It signals that Nārada’s singing is delightful because of the way in which he accompanies it with his fingers dancing up and down his veena’s fretboard.

[As an adjective] It signals that the stories of the Supreme Lord, which Nārada is singing in the vernacular, are delightful because they are full of His deeds and descents that are repeatedly done for our benefit. For, as He Himself tells us (in the Bhagavad Gītā): sambhavāmi yuge yuge “I take birth in age after age”.

|| Srī-Padmāvatī-nāyikā-sameta-Śrī-Śrīnivāsa-parabrahmaṇe namaḥ ||

There are a couple of slightly more esoteric connections to reinforce this claim. First, the use of the word gāyati “sings”. While this can refer to singing in general, it can also refer to the singing of the Sāma Veda (Sāma-gāna, as it is known). But no Veda would ever be described as bhāṣā, so this would have to refer to a “vernacular [Sāma] Veda”, so to speak. This unprecedented honor is specifically extended to the Tiru-vāy-mŏzhi of Nammāzhvār.

Second, Nammāzhvār himself describes the Lord in his famous Ārāvamudē song as yāzhin isaiyē “o music of the veena!” (TVM V.8.6), which further reinforces the connection with Nārada’s playing the veena in this verse.

Share this post