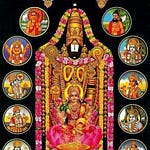

On this holy day of Ratha Saptamī in the Krodhi year, let us turn to the second verse of the Śrī Veṅkaṭeśa Stotram.

sa-Caturmukha-Ṣaṇmukha-Pañcamukha- -pramukhâ-akhila-daivata-mauli-maṇe! | śaraṇâgata-vatsala! sāra-nidhe! paripālaya māṃ Vṛṣa-śaila-pate! || (VSt 1) स-चतुर्मुख-षण्मुख-पञ्चमुख- -प्रमुखा-ऽखिल-दैवत-मौलि-मणे ! शरणागत-वत्सल ! सार-निधे ! परिपालय मां वृष-शैल-पते ! ॥

O Lord who is the crest-jewel for all the gods, led by four-faced Brahmā, six-faced Kārtikeya, and five-faced Śiva! O Lord who is infinitely tender (like a mother to her babies) to those who have taken refuge in You! O Lord who is the treasure-house of all essences! Rescue me, nurture me, nourish me, O Lord of Bull-mountain!

The structure of the verse

Like the first verse of the Stotram, this verse too is quite simple from a grammatical perspective: three full lines and another half-line are all vocatives (sambodhana) to Lord Śrīnivāsa, with just one finite verb: paripālaya mām. Let us then begin by examining this verb and its dependent.

The finite verb and its object

In a number of recitations, the word mām (“me”) is stretched out for eight whole morae, underscoring and emphasizing our individual requests seeking the favor of Lord Veṅkaṭeśvara. The word is in the accusative (dvitīyā) because its referent—us—is the patient (karman) of the action (kriyā) expressed by the finite verb (tiṅ-anta) paripālaya: we are the objects of the action of paripālana (whose meaning we will explore shortly) that is to be carried out by the Lord.

This is a case where a purely grammatical account can nevertheless be read in theological terms. According to Pāṇini, the1 definition of the term karman is given in sūtra I.4.49: kartur īpsitatamaṃ karma (“the patient is that which is most desired by the agent”). Understood purely grammatically, there are a number of issues with this definition, which are addressed by Pāṇini himself as well as by numerous later grammarians. However, in our theological context, we can embrace this sūtra’s meaning wholeheartedly: each of us is wholly and fully īpsitatama, the most desired, the most special, the most favored recipient of Lord Veṅkaṭeśvara’s grace.

Far from God not playing favorites, He most certainly does play favorites—with every single one of us, every moment, for eternity!

The first name

The first name here takes up the entire first two lines of the verse, and should also remind us of Verse 6 of the Suprabhātam, in which the same four-faced Brahmā, five-faced Śiva, and six-faced Skanda are referred to. In that context, the gods are described as they approach Lord Veṅkaṭeśvara to awaken Him in the morning. In this context, the Lord is described as the crest-jewel (mauli-maṇi) for all of these gods: in other words, they take refuge in Him and exalt Him as the devâdhideva (“Overlord of all the Gods”), the devatā-sārvabhauma (“Emperor of all Divinities”), the akhilâṇḍa-koṭi-brahmāṇḍa-nāyaka (“Sovereign over the multiverse comprised of myriads upon myriads of cosmoses, without any exceptions”).

We can also play with the English translation a little bit here: Lord Śrīnivāsa isn’t merely on the gods’ heads; He is on their minds as well. In other words, He is whom they meditate upon; He is whom they contemplate. And if we extend this line of thinking further—they are who they are because He has been on their minds!

The second name

If the first name emphasizes Lord Śrīnivāsa’s paratva (His transcendence, His absolute and utter superiority), the second name (śaraṇâgata-vatsala) depicts His sauśīlya (His graciousness and gentleness to His devotees). This shows us His dayā, His loving maternal affection: He accepts us for who we are.

In fact, according to Swāmī Maṇavāḷa Māmunigaḷ, the ācārya of Aṇṇan Swāmī, this quality of vātsalya2 plays an absolutely critical role in the Supreme Divine’s acceptance of us despite (or even because of!) our sinful natures. Think about the moment of birth, when a newborn infant emerges from its mother’s womb, covered in all sorts of bodily fluids. In virtually any other context, we might find this icky, messy, or even disgusting. And yet to the mother, who is herself utterly exhausted and in great pain, it is a moment of magic and delight to take her child in her arms and to hold it to her bosom and to nurse it with her own milk. This is vātsalya in our world, and it is this vātsalya magnified a millionfold in the Divine that envelops us when we incline ever so slightly towards Him.

The third name

The third name (sāra-nidhi) refers to Lord Śrīnivāsa being the innermost essence of everything. There are a number of ways to understand this concept, and I will focus on just one for now: a core tenet of Viśiṣṭâdvaita theology, that the Divine pervades all of creation, both sentient and insentient. Sometimes known as śarīra-śarīri-bhāva, or “the relationship of the embodied soul to its embodiment”, this draws an analogy between the inherence of the soul in the body of a living being and the immance of the Divine in both bodies and souls.

This name thus emphasizes Lord Śrīnivāsa’s antaryāmitva: His being the Innermost Controller of all things, sentient and insentient alike. He is the ultimate Charioteer of our souls, in effect.

The fourth name

All the names so far have had deep theological and emotional resonances: they refer either to cosmic properties of the Divine or to core feelings. However, all of them are location or form-agnostic. The fourth name, Vṛṣa-śaila-pati, concretizes the Divine: that same Lord who is worshipped by the gods, who is love personified, who is the innermost heart of things is also the very Lord who has manifested Himself on top of the hills of Tirupati. It thus emphasizes His saulabhya (His easy accessibility, especially in these days when all the infrastructure to visit the Lord’s mountaintop shrine has been built out).

A hidden reference?

To me, this verse’s encapsulation of four essential properties of Lord Veṅkaṭeśvara and its plaintive invocation to Him to protect us brings to my mind the Gajendra-mokṣa episode.3 All it takes for the elephant to be rescued from the jaws of the crocodile is the elephant’s sincere thought of taking refuge in the Divine, not even necessarily articulated in a human voice. Even as all the gods give up, the Lord shows up in person to save the elephant. We can correlate the four names in this verse to this incident as follows:

The first name, emphasizing His paratva (absolute superiority), depicts the Lord’s unique ability to save the elephant even after all other deities had washed their hands off the matter.

The second name, emphasizing His [or perhaps we should say Her] vātsalya (motherly affection) and sauśīlya (graciousness). The Supreme Being cares about the wellbeing of every being in creation, not just human beings.

The third name, emphasizing His antaryāmitva (immanent lordship), underscores His all-pervading nature and His ability to perceive the elephant’s existential crisis even if it had not been articulated explicitly.

The fourth name, emphasizing His concrete manifestation on earth, refers to His showing up in person to save the elephant, and by extension to save us all as well.

The Gajendra-mokṣa episode is recommended for meditation first thing in the morning for all Śrīvaiṣṇavas even while they are still in bed.

|| Śrī-Padmāvatī-nāyikā-sameta-Śrī-Śrīnivāsa-parabrahmaṇe namaḥ ||

Even calling this “the” definition of the term karman is incorrect. For one, there are another four sūtras following this that further extend or modify the applicability of the term karman. For another, all of these sūtras fall under the scope of I.4.1 ā-«kaḍārā»d ekā saṃjñā “From here up until (II.2.38) kaḍārāḥ karmadhārayaḥ, only one technical designation is applicable” and I.4.2 vipratiṣedhe paraṃ kāryam “In case of overlapping (technical designations), the latter alone should be applied”. As a result of these two rules, we should in effect append a warning to every definition in this scope that says “this definition might be constrained or modified by the succeeding rules!”.

This word derives from the Sanskrit vatsalā, or the cow seen in relation to its calf. The abstract noun vātsalya refers to the tenderness, boundless affection, and gentle care that a cow showers upon its newborn calf.

This story is recounted in, for instance, the third chapter of the eighth canto of the Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam.

Share this post