Verses 25 and 26 both share a common theme of describing devotees of Lord Śrīnivāsa who gather in the morning to serve Him. Where in verse 25, they were busy with bringing the sacred water for the Lord’s tiru-mañjanam, in verse 26 they are busy with singing His praises and wishing for His well-being.

bhāsvān udeti, vikacāni saroruhāṇi, sampūrayanti ninadaiḥ kakubho vihaṅgāḥ | Śrīvaiṣṇavāḥ satatam arthita-maṅgalās te dhāmâ āśrayanti tava Veṅkaṭa! suprabhātam || (VSu 26) भास्वान् उदेति, विकचानि सरोरुहाणि, सम्पूरयन्ति निनदैः ककुभो विहंगाः । श्रीवैष्णवाः सततम् अर्थित-मंगलास् ते धामा ऽऽश्रयन्ति तव वेङ्कट ! सुप्रभातम् ॥

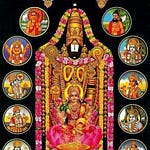

The sun has risen, the lotuses have blossomed, the quarters are filled with the sweet chirping of birds; Śrīvaiṣṇavas who are ever-dedicated to Your flourishing have congregated at Your abode: O Veṅkaṭa, a blessed morning unto You!

The imagery of this verse, like other earlier verses that depict nature, can also be interpreted in multiple ways.1 Let us first look at the plain meaning before turning to symbolic interpretations.

The plain meaning of the verse

The sun has fully risen by now, and now illuminates the whole eastern quarter. The lotuses too have fully blossomed, now that the sun is out. As the day’s activities unfold in broad daylight, birds are chirping everywhere. This description is mirrored in the first line of the final verse of the Tirup-paḷḷi-yĕḻucci:

kaḍi-malar kamalaṅgaḷ malarndana yivaiyō Kadiravan kanaik-kaḍal muḷaittanan ivanō (TPĔ 10a)

O, are these the fragrant red lotuses that have fully blossomed? Is this the sun who has sprouted atop the thundering ocean?

It is in this idyllic setting that devout followers of Lord Veṅkaṭeśvara, who seek nothing for themselves but only wish to pray directly for the Lord’s welfare, come to Lord Śrīnivāsa in the morning and sing His praises as the morning prayers are being concluded.

Metaphorical interpretations galore

As with other nature-themed verses in the Suprabhātam, here too we should look for spiritual messages encoded in natural garb. I will present two options here.

Interpretation 1: The power of dhvani

We have already investigated the imagery of lotuses being made to blossom by the Sun’s rays in verse 12. Here, though, there is no explicit causality being drawn between the sunrise and the blossoming of the lotuses; they are just presented in sequence.

As a result, this verse suggests that we too should be entreating Lord Śrīnivāsa to turn His loving face in our direction, illuminating our lives fully, and to open His lotus-eyes towards us so that we may rejoice in His lovely Dayā-filled glances. (As before, we should treat every mention of the lotus as a reference to Padmāvatī Tāyār).

The second line about the birds’ chirping filling all the quarters further suggests behavior that we should be emulating: reciting the names and stories of the Divine so that His glory pervades the universe.

Interpretation 2: The power of samāsôkti

Under the previous interpretation, we take the natural ideal presented in the verse as being suggestive of an ethical ideal that we should be living up to. Here is a second possibility as well, as if to illustrate the infinitude of interpretations when thinking of the Divine.

This time around, we treat the first half of the verse as a descriptor of the Śrīvaiṣṇavas who are referred to in the third line. Taking the first half of the verse in isolation, the literary ornament (alaṅkāra) applicable here is known as samāsôkti: we describe one thing, and in doing so, we end up describing something else as well.2 Now the verse taken as a whole may not strictly count as samāsôkti, as the second half of the verse explicitly refers to the devotees of the Lord; however, for our purposes, this will do for now.3

Thus, the birds (vihaṅga) should bring to our mind the devotees of the Lord for an etymological reason: the word vihaṅga literally means “sky-goer”, which can of course refer to birds, but also to devotees who are guaranteed to ascend to the Highest Heaven. (We can also get creative and think of this as a reference to the temple to Lord Śrīnivāsa atop Tirumalai—so high that it might as well be up in the sky!) This then reinforces the connection between the birds’ behavior (filling all the quarters with their chirping) and the devotees’ (filling all the quarters with their chanting).

The lotuses (saroruha) that have blossomed (vikaca) then refer to the heart-lotuses (hṛdaya-paṅkaja) of these same devotees, which have been opened up by devotion and contemplation of the Lord.4 The water (saras) from which these lotuses have arisen is then akin to the sacred, nectarine speech of the Vedic seers, the Āḻvārs, and the Ācāryas of the Śrīvaiṣṇava tradition, which provides the foundation for our spiritual growth (-ruha reminding us of ārohaṇa “ascent”).

And finally, of course, the sun (bhāsvān) should bring to mind the infinitely radiant Supreme Sun, Who shines both in/as the highest heavens and in/as our innermost selves.5 Just as the terrestrial sun makes terrestrial lotuses blossom, so too is this Cosmic Sun the ultimate reason for the blossoming of the heart-lotuses of the true devotees of Lord Veṅkaṭeśvara. Living in the Lord’s light, they come to His sacred shrine to see Him with both their inner sight and their physical eyes. Melting in the warmth of this Sun, all they can think of is singing His praises and praying for His wellbeing.

Praying for the welfare of the Divine

On that note, let us explore this idea further: why should we as humans pray for the welfare of the Divine? This makes no sense prima facie: one can glorify the Lord, one can sing the praises of the Lord, one can beseech the Lord, but how does it make sense for mere humans to pray for the wellbeing of the Divine?

This question—and its answer—is very much along the lines of the question with which we opened the Suprabhātam: how does it make sense for humans to awaken the Divine in the morning when the Divine transcends space and time and is not limited by human-like fluctuations in awareness like sleep or dreams?

The response is straightforward:

We wish the welfare of the Divya Dampati so that we can rejoice and shelter in Their shade. Not that They need our prayers—They are totally self-sufficient—but that it does us good to wish Them good and to wish Their followers good.

We might go even further and add that, for those whose heart-lotuses have truly blossomed, the very idea of praying to the Lord for self-interested reasons no longer makes sense: These devotees have transcended their selfish egos and instead live life entirely for living out the Divine purpose of their lives.

Verses from the Śrīvaiṣṇava sāṯṯṟumuṟai

This theme of praying for the welfare of the Divine is deeply ingrained in the Śrīvaiṣṇava tradition. It shows up repeatedly, for instance, in the Tirup-pallāṇḍu of Pĕriyāḻvār (perhaps the most widely recited of any Śrīvaiṣṇava devotional poem), and also in the Śrī Veṅkaṭeśa Maṅgalam of Śrī PB Aṇṇan Swāmī. The theme is also prevalent in the verses of the sāṯṯṟumuṟai, the closing liturgy of every prayer and ritual performed according to Śrīvaiṣṇava practices. (Indeed, it is no coincidence that the Suprabhātam invokes this theme at this juncture—it is in fact meant to bring to mind the morning worship’s sāṯṯṟumuṟai.)

I will highlight just two verses from the sāṯṯṟumuṟai here.

First, of course, the opening verse of the Tirup-pallāṇḍu itself:

pallāṇḍu pallāṇḍu pallāyiratt’ āṇḍu pala kōḍi nūṟ’ āyiram mallāṇḍa tiṇ-tōḷ Maṇi-vaṇṇā! un śēv-aḍi śĕvvi tiruk-kāppu

Many years Many years Many thousands of years Many tens of millions of hundreds of thousands of years: O broad-shouldered wrestler-subduing Sapphire-hued Lord! May the beauty of Your lotus-red feet be protected.

As one of the most important verses in the Śrīvaiṣṇava tradition, this has attracted extensive exegesis and elaboration from the great scholars of the community, and as a result this “translation” captures nothing more than a very superficial sense of the profundity of the verse.

Next, another verse, this time in Sanskrit, that captures this idea of proclaiming the glory of the Divya Dampati in all directions:

sarva-deśa-daśā-kāleṣv avyāhṛta-parākramā | Rāmānujâ-ārya-divyâ-ājñā vardhatām abhivardhatām ||

In all lands, in all climes, at all times, its conquest remains inexorable: May the divine instruction of the noble Rāmānuja flower, may it flourish!

Verses from the Divya-deśa-maṅgalāśāsana of Swāmī Deśikan

It can also take the form of the following verse, in which Swami Deśikan prays to Lord Śrīnivāsa to Himself protect and guard and nurture His own glory.

praśamita-Kali-doṣāṃ prājya-bhogâ-anubandhāṃ samudita-guṇa-jātāṃ samyag-ācāra-yuktām | śrita-jana-bahu-mānyāṃ Śreyasīṃ Veṅkaṭâdrau Śriyam upacinu nityaṃ Śrīnivāsa! tvam eva ||

She pacifies the flaws of the degenerate Age of Kali, She gives rise to unlimited enjoyment, She arises in good folk filled with virtues, She is ever associated with proper behavior, She is greatly honored by those who surrender to Them: Such is the superlative Śrī of Veṅkaṭâdri. Guard Her and make Her flourish Yourself, O Lord Śrīnivāsa of Veṅkaṭam the abode of Śrī Herself!

This lovely verse is taken from the Rahasya Navanītam, one of Swāmī Deśikan’s shorter esoteric texts written in the maṇipravāḷa fusion of Sanskrit and Tamil characteristic of Śrīvaiṣṇava prose. It is one of five verses by Swāmī Deśikan that share the same theme and similar wording, dedicated to the four most important shrines for Śrīvaiṣṇavas (Śrīraṅgam, Tiruveṅkaṭam, Kāñcīpuram, and Mēlkōṭĕ). Although each occurs in a different text, they are assembled together into an integrated Divya-deśa-maṅgalâśāsana, a prayer for the wellbeing of the most important terrestrial manifestations of the Divine. Since reciting these 5 beautiful verses on a daily basis can help cultivate humility and devotion towards the sacred icons of the Divine, I will at some point in the future post a recitation and translation of this short text, with the permission of the Divine.

|| Śrī-Padmāvatī-nāyikā-sameta-Śrī-Śrīnivāsa-parabrahmaṇe namaḥ ||

And not just the imagery either! This verse contains the word ninadaiḥ in the exact same location as does Verse 10. There we had buzzing bees, and here we have chirping birds—but all of this is in service of Lord Śrīnivāsa.

The Kuvalayânanda of Appayya Dīkṣita defines and exemplifies samāsôkti as follows:

samāsôktiḥ parisphūrtiḥ prastute aprastutasya cet | «ayam Aindrī-mukhaṃ paśya! raktaś cumbati candramāḥ» || (KuĀK 61)

If the thing not-presented shines forth when the thing presented is stated explicitly, it is samāsôkti: “Look! The reddened moon kisses the eastern (sur)face.”

As should be clear, the description of the moon kissing the eastern horizon immediately brings to mind the hero, flushed with passion, kissing his beloved’s face.

For instance, we could make the argument that the verse upon first reading simply presents a list of objects: the sun, the lotuses, the birds, and (after a mandatory pause) the Śrīvaiṣṇavas. Thus, even though the Śrīvaiṣṇavas are explicitly presented in the verse later on, there is no direct indication in the verse of them being metaphorically referred to as birds or otherwise. Consequently, a weak defense of this being samāsôkti could still be mounted.

Again, as Appayya Dīkṣita says in the opening verse of his Varadarāja-stava (not to be confused with the text of the same name by Swāmī Kūrattāḻvān) and, at least in some manuscripts, one of the opening verses of the Kuvayalānanda as well:

udghāṭya yoga-kalayā hṛdayâ-’bja-kośaṃ dhanyaiś cirād api yathā-ruci gṛhyamāṇaḥ | yaḥ prasphuraty avirataṃ paripūrṇa-rūpaḥ śreyaḥ sa me diśatu śāśvatikaṃ Mukundaḥ || (AVRS 1)

May Mukunda, His infinitely full form constantly pulsating, grasped by the blessed (who have unfurled the petals of their heart-lotuses through the art of yoga) in whatever form delights them, for as long as they want, direct me to eternal felicity!

As the Chāndogya Upaniṣad says, identifying the Supreme Light with the Innermost Light:

atha yad ataḥ paro divo jyotir dīpyate viśvataḥ pṛṣṭheṣu sarvataḥ pṛṣṭheṣv anuttameṣû uttameṣu lokeṣv idaṃ vāva tad yad idam asminn antaḥ puruṣe jyotiḥ | (ChU 3.13.7)

Thus, that light which shines higher than high heaven, above the cosmos, above everything, in the most exalted and unexcelled realms—that is this very light which is inside the Inner Person.

Share this post