Continuing with the theme of nature worshipping Lord Srinivasa from last time, our verse for today also brings up natural imagery: this time of parrots. But as we will soon see, there is a lot more going on here.

unmīlya netra-yugam uttama-pañjara-sthāḥ pātrâ-’vaśiṣṭa-kadalī-phala-pāyasāni | bhuktvā sa-līlam atha keli-śukāḥ paṭhanti Śeṣâdri-śekhara-vibho! tava suprabhātam || (VSu 8) उन्मील्य नेत्र-युगम् उत्तम-पंजरस्थाः पात्रा-ऽवशिष्ट-कदली-फल-पायसानि । भुक्त्वा सलीलम् अथ केलि-शुकाः पठन्ति शेषाद्रि-शेखर-विभो ! तव सुप्रभातम् ॥

Opening their two eyes, the playful parrots in the highest cages consume the bananas and milk left overnight in vessels for You and then sportively sing: O all-pervading Almighty atop Seshadri, a blessed morning unto You!

On the surface, this is a very straightforward, perhaps even boring, verse: the parrots in Tirupati eat the leftovers for Lord Śrīnivāsa and then sing. What's the big deal here?

There are, however, a number of subtle hints that suggest we must interpret this verse in deeper and richer ways.

A literal interpretation of the verse

Even if we limit ourselves to the direct, literal imagery of the verse, we find some beautiful details to ponder upon.

Parrots

First is the mention of parrots (śukāḥ): Parrots are very significant because they reproduce human speech honestly. A common technique in Sanskrit poetry to indicate the sacredness of a place is to depict the parrots there as reciting the Vedas.

Our first glimpse of play

But these parrots are not ordinary parrots either: they are keli parrots. I have translated the word keli as “playful”, which is indeed one of its senses,1 but it is frequently used in poetry to indicate amorous play.2 Thus, these parrots belong to the innermost chambers (antaḥ-pura) of the temple and are hence witnesses to the most secret, most intimate nightly union of the Divine Couple, inaccessible to any humans.3

And even there these particular parrots are special, as they dwell (-sthāḥ) in the highest / best (uttama-) cages (-pañjara-).

Furthermore, these parrots do three significant things: they open both their eyes, and then they consume the leftover food and milk of Lord Śrīnivāsa, and then they sing/chant playfully.

Eyes and vision

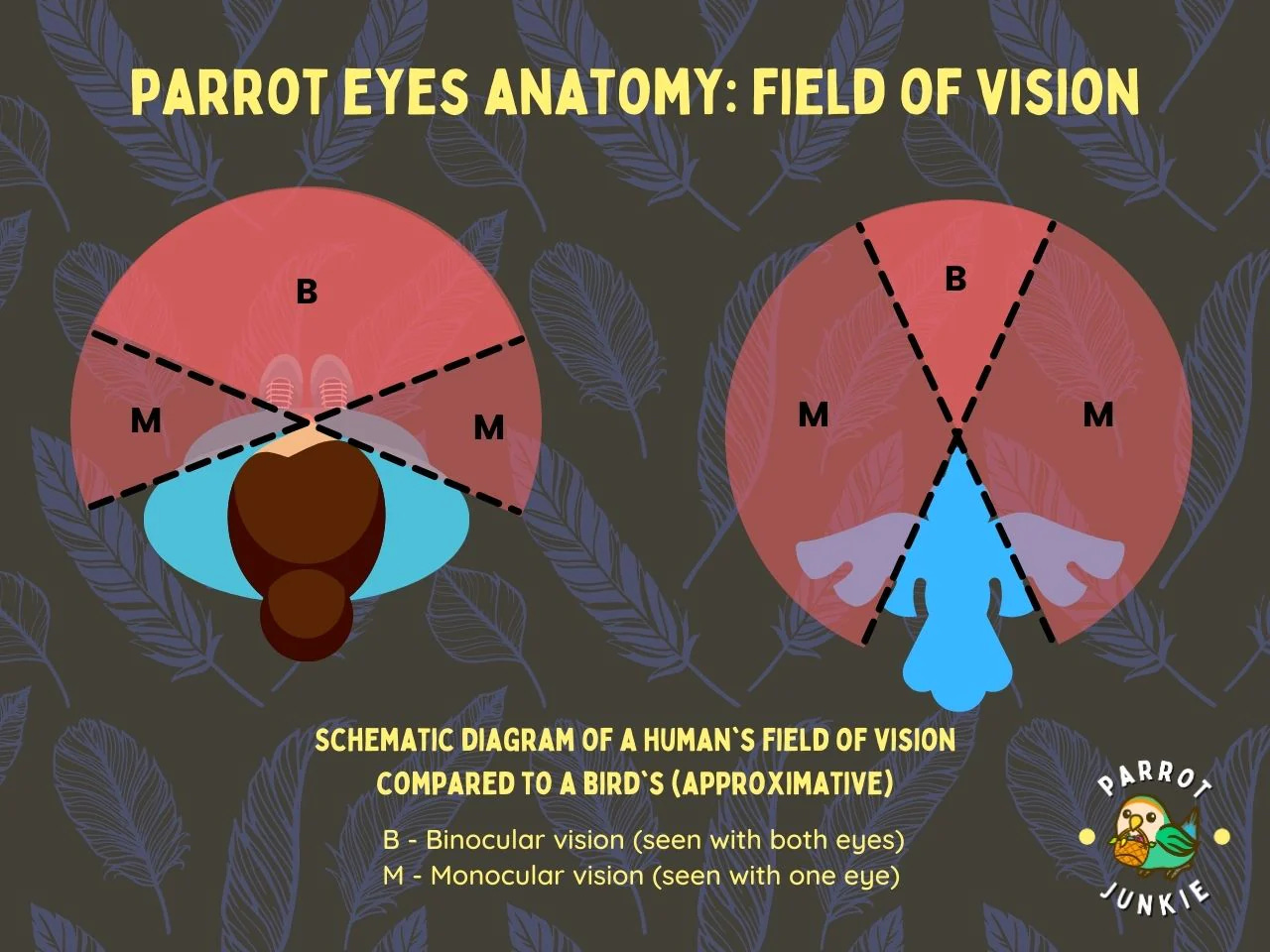

The verse is clear that the parrots open both their eyes. Now this is of course normal, so why draw attention to it? We may note that parrots’ eyes are not like human eyes. Our eyes are mounted on the front of our faces (giving us binocular vision); parrots’ eyes are mounted laterally, on the sides of their faces.

Thus, these parrots, when they wake up to see Lord Śrīnivāsa, they do so with one eye, while, with the other, they are looking back—at us, beckoning us to come closer. They are simultaneously immersed in the Divine and in the mundane.

Leftovers and offerings

Having opened their eyes, the parrots notice the leftover (avaśiṣṭa) bananas and milk for Lord Veṅkaṭeśvara, and consume them. This is of course what all of us do at the temple, consuming Bhagavat-prasāda and thus hoping to partake of the pleasure of the Divine Couple.

Singing for the Lord

Physically satiated with the milk and bananas, and spiritually satiated with their darśana (vision) of Lord Veṅkaṭeśvara, the parrots now sing in delight. What do they chant? Whatever they hear most often in the sanctum sanctorum: perhaps the resounding call of “Govinda, Govinda!”, or perhaps simply the final line of this verse: Śeṣâdri-śekhara-vibho! tava suprabhātam!

A metaphorical interpretation of the verse

The literal interpretation of this verse is beautiful in and of itself. But we will now see a whole additional layer of meaning that can be stacked onto this verse!4

Parrots, redux

We have already seen that to be a parrot is to be an intelligent being who grasps the truth immediately and who proclaims it freely and openly. Additionally, the parrots’ proximity to the Lord’s most intimate moments indicates their ability to access the secrets of the universe unavailable to mere mortals.

All this taken together suggests that we should understand the parrots metaphorically to be the saints and philosophers of the Śrīvaiṣṇava tradition, who enjoy privileged access to the Divine.5 Furthermore, these parrots’ singing (paṭhanti) the glories of the Lord is further evidence that they are in fact saints.

Eyes, redux

The fact that the parrot-saints have opened both of their eyes is a pointer to us to open both of our eyes as well. But what might these two eyes be for us, especially the fact that the parrot-saints are simultaneously looking at both Lord Śrīnivāsa and at the devotees gathered at His doorstep? I can think of a number of pairs:

the eye of bhakti (devotion) and the eye of jñāna (gnosis). We need both to see the Divine Couple fully.

the this-worldly (aihika) eye and the other-worldly (āmuṣmika) eye. We cannot abandon the one for the other but rather need both in operation together.

the literal eye and the figurative eye. This is what we are doing here with this verse. We stick to the literal meaning, never abandoning it, and also enrich it with extra suggestive meanings. Again, we need both.

Offerings, redux

Again notice that there are two offerings here: bananas and milk. We may therefore see if these can be understood symbolically as well, in keeping with the previous interpretations. There are two key differences between bananas and milk:

Milk is liquid and can be drunk even by infants, while bananas are solid and require some chewing and digesting.

Milk can be consumed effortlessly while bananas need to be peeled to be eaten.

This yields multiple different symbolic interpretations of milk and bananas:

On the path of bhakti, we can enjoy the Divine like milk, effortlessly and easily. But the path of jñāna is trickier as it involves some amount of labor on our parts, to pluck, then peel, then chew, then digest the banana—and not everybody can do it.

This-worldly deeds are often difficult to achieve, and not always accessible to everyone. Otherworldly success, however, is open to all of us just as effortlessly as mother's milk: by surrendering to the Father and Mother of the Cosmos.

We can also think of the Sanskrit Vedas versus the Tamil Divya Prabandham of the Āzhvārs in a similar fashion:

the former take effort to learn and are not open to everyone.

the latter are accessible to absolutely everybody and are also easier to comprehend (at least for Tamil speakers!).

The importance of play

Finally, what is the result of this waking up and eating prasāda? The result is that the parrots sing playfully and joyfully. The idea of līlā here is very important theologically, and we can go into great depth into it. But the key idea is that free play—joyful, unrestricted, self-generated, unmotivated by external goals, unending—is the best way to imagine the deeds of the Divine Couple.

It is also a good example for us to emulate in our acts of devotion:

When we, spiritually awakened, partaking of the blessings of Ṡrīnivāsa Pĕrumāḷ and Padmāvatī Tāyār, sing Śeṣâdri-śekhara-vibho! tava suprabhātam in a state of free delight, motivated by nothing other than the sheer joy of celebrating Them—what greater blessing can there be?

|| Śrī-Padmāvatī-nāyikā-sameta-Śrī-Śrīnivāsa-para-brahmaṇe namaḥ ||

In Tamil, the word gēli கேலி is used to mean playing around, having fun, and generally being unserious.

Thus, the opening verse of the Gīta-Govinda of Jayadeva reads:

Rādhā-Mādhavayor jayanti Yamunā-kūle rahaḥ-kelayaḥ || (GīGo I.1d)

Triumphant are the intimate pastimes on the banks of the Yamunā of Rādhā and Kṛṣṇa Mādhava!

This nightly union of the Divine Couple is celebrated in both Tamil and Sanskrit. Āṇḍāḷ sings in her exquisite Tiru(p)-pāvai as follows:

kuttu-viḷakk’ ĕriya kōṭṭu(k)-kāl kaṭṭil mēl mĕtt’ ĕṉḏṟa pañja śayanattin mēl ēṟi kŏtt’ alar pūṅ-kuzhal Nappinnai kŏṅgai mēl vaittu(k) kiḍanda Malar-mārbā! vāy tiṟavāy! (TP 19ab) குத்து விளக்கு எரிய கோட்டுக் கால் கட்டில் மேல் மெத்தென்ற பஞ்ச சயனத்தின் மேல் ஏறிக் கொத்தலர் பூம் குழல் நப்பின்னை கொங்கை மேல் வைத்துக் கிடந்த மலர் மார்பா வாய் திறவாய்

O Kṛṣṇa with flower-garlands on your chest! Even as You rest upon the bosom of Nappinnai with bunches of blossoms in her hair who lies upon a softer-than-cotton mattress atop an ivory-legged bed illuminated by beautiful floor-lamps, Awake and address us!

Similarly, Swāmī Vedānta Deśika celebrates the waking up of Lord Varadarāja of Kāñcīpuram in his Varadarāja-Pañcāśat as follows:

anibhṛta-parirambhair āhitām Indirāyāḥ kanaka-valaya-mudrāṃ kaṇṭha-deśe dadhānaḥ | phaṇi-pati-śayanīyād utthitas tvaṃ prabhāte Varada! satatam antar mānasaṃ sannidheyāḥ || (VPś 47)

Bearing upon Your neck the imprint of Lakṣmī’s golden bangles pressed by Her repeated embraces You are arisen at dawn o boon-granting Varada! from Your couch — Ādi-śeṣa, lord of serpents: May You be eternally resident in my innermost heart-shrine!

For those who are well-versed in Sanskrit literary theory (alaṅkāra-śāstra), what I’m doing here is basically what Mammaṭa Bhaṭṭa describes in the second ullāsa of his famous Kāvya-prakāśa. After outlining the three different kinds of meanings that words and sentences can have—directly expressed (vācya), indirectly indicated (lakṣya), and suggested (vyaṅgya)—he then goes on to claim that all of these meanings can then additionally suggest new meanings:

sarveṣāṃ prāyaśo ’rthānāṃ vyañjakatvam apî ’ṣyate | (KāPra [II] 7ab)

Generally speaking, all [three] meanings also additionally have the power to suggest additional meanings.

Mammaṭa Bhaṭṭa then dives a little deeper into how this secondary power of suggestion operates in the third ullāsa:

vaktṛ [1]-boddhavya [2]-kākūnāṃ [3] vākya [4]-vācyâ [5]-’nya-sannidheḥ [6] || prastāva [7]-deśa [8]-kālâ [9]-’’der vaiśiṣṭyāt pratibhā-juṣāṃ | yo ’rthasyâ ’nyâ-’rtha-dhī-hetur vyāpāro vyaktir eva sā || (KāPra [III] 21cd – 22)

It is the semantic operation of suggestion by an existing meaning [whether directly expressed, indirectly indicated, or suggested] which gives rise to the cognition of a further meaning for those endowed with poetic insight, based upon the particularities of such things as [1] the speaker, [2] the addressee, [3] intonation, [4] the utterance as a whole, [5] the directly expressed meaning, [6] the proximity of another (hidden addressee), [7] the general context, [8] the place, [9] the time, and other factors.

In the case of this specific verse from the Suprabhātam, the first half of this post examines the surface-level meaning, which we can think of as the vācya (directly expressed) meaning. The second half of this post then looks at the additional layers of suggested meaning on top of this.

We can see this indirectly in Āṇḍāḷ’s Tiru(p)-pāvai too, in which one of the girls (TP 15) who is woken up to join the party waking Kṛṣṇa is called a “young parrot” (iḷaṅ-kiḷiyē இள்ங்கிளியே). According to the traditional commentaries, these girls are all identified with the foremost of the Lord’s devotees and saints.

Share this post