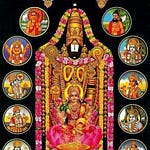

Last time, we saw the gathering of the great gods at Tirupati to celebrate the daily awakening of Lord Śrīnivāsa. This time, we will see how nature—which is also divine in its own way—also worships the Supreme Lord in its own way.

īṣat-praphulla-sarasīruha-nārikela- pūga-drumâ-’’di-sumanohara-pālikānām | āvāti mandam anilaḥ saha divya-gandhaiḥ Śeṣâdri-śekhara-vibho! tava suprabhātam || (VSu 7) ईषत्-प्रफुल्ल-सरसीरुह-नारिकेल-पूग-द्रुमा-ऽऽदि-सुमनोहर-पालिकानाम् । आवाति मन्दम् अनिलः सह दिव्य-गन्धैः शेषाद्रि-शेखर-विभो ! तव सुप्रभातम् ॥ 7 ॥

A breeze blows gently, redolent with divine fragrances wafting from supremely captivating orchards and groves of lotuses, only slightly blossomed tender coconuts arecanuts, and more: O all-pervading Almighty atop Seshadri, a blessed morning unto You!

The connection between nature and the Divine

People today sometimes introduce a divide between nature (which is sometimes seen as inert, entirely understood, governed by the laws of physics, and so on) and the Divine. However, such a divide would seem entirely artificial to just about anybody holding traditional viewpoints in India, from Vedic times down to the present day. In this view, Agni is not just the “god of fire”, but also fire itself—every fire you see is the deity Agni himself. Similarly, Vāyu is not just the “wind-god”, but literally the very air itself—a gentle breeze, a terrifying tornado, a continent-sized hurricane: all of these are Vāyu in various forms.1

From this perspective, this verse is not actually so different in spirit from the previous verse: As in the previous verse, a divinity (here, Vayu, the [god of the] wind) is coming to pay his respects to Lord Veṅkaṭeśa. This god brings as offerings the fragrances of various plants delightful to the Lord. It is thus not just humans and gods but also the whole natural world that seeks to make its morning offerings to Lord Śrīnivāsa.

A Vedic breeze

The verb āvāti “he blows [towards]” in this verse reminds me of the Ghoṣa-sānti recitation from the Taittirīya Āraṇyaka of the Kṛṣṇa Yajur Veda, which includes the following lines:

ā Vāta! vāhi bheṣajaṃ, vi Vāta! vāhi yad rapaḥ | (TaitĀ IV.42.1)

To us o Wind! blow healing; From us o Wind! blow all that is affliction.

Indeed, this is but one of many references in the Ghoṣa-śānti to the dual power of wind (Vāta) to both heal and to purify—Vāta is literally the first deity invoked in this powerful purificatory and pacifying chant. You can listen to a flawless rendition of the Ghoṣa-śānti on YouTube here.

A Tamil perfume

In parallel to the Veda, this verse is also clearly perfumed by two different verses from Tŏṇḍar-aḍi(p)-pŏḍi Āzhvār’s Tiru(p)-paḷḷi-yĕzhucci. First:

kŏzhuṅ-kŏḍi mullaiyin kŏzhu-malar aṇavi kūrndadu guṇa-diśai mārutam iduvō? (TPĔ 2a) கொழுங் கொடி முல்லையின் கொழு மலர் அணவி கூர்ந்தது குண திசை மாருதம் இதுவோ

Is this the easterly breeze spreading the fragrance of bunches of beautiful blossoms clustered on lovely jasmine vines?

And similarly, in the next verse:

paim-pŏzhil kamugin maḍal-iḍai(k) kīṟi vaṇ-pāḷaigaḷ nāṟa vaigaṟai kūrndadu mārutam iduvō? (TPĔ 3c) பைம்பொழில் கமுகின் மடலிடைக் கீறி வண்பாளைகள் நாற வைகறை கூர்ந்தது மாருதம் இதுவோ

Is this is the dawn breeze diffusing the aroma of fresh buds split down the middle of arecanut trees growing in verdant groves?

Implications of the imagery

Two minor but beautiful details to note for us:

The lotuses are īṣat-praphulla, hardly blossomed at all. This is meant to suggest that the sun is only just starting to rise, and that only the first rays of the sun have touched the lotus-petals so far.

The adjective that describes the orchards is sumanohara, which can be understood as a compound (samāsa) in two different ways:

su + manohara: meaning “supremely captivating”

sumano + hara: meaning “captivating the good-hearted”

That is to say, we must already be sumanas, people of good hearts, attuned to Pĕrumāḷ and Tāyār, in order to recognize that each and every aspect of nature is already and always singing Their praise in its own way.

We cannot acquire this secret understanding of the Suprabhāta unless and until our hearts and minds are already turned to the Divine Couple.

|| Śrī-Padmāvatī-nāyikā-sameta-Śrī-Śrīnivāsa-parabrahmaṇe namaḥ ||

One way in which the sacred, personified view of nature continues to persist is with rivers: even today, the Gaṅgā, for instance, is both the life-giving water-stream running through North India as well as the goddess whose physical bodily form is this river.

Share this post