Last time’s verse depicted an inward motion towards the center of the universe. This verse reverses the direction of motion outwards, encompassing the entire cosmos. As we see, it also beautifully integrates temple ritual with cosmic processes.

dhāṭīṣu te Vihaga-rāja--Mṛgâdhirāja-- Nāgâdhirāja--Gaja-rāja--Hayâdhirājāḥ | sva-svâ-adhikāra-mahimâ-ādikam arthayante Śrī-Veṅkaṭâcala-pate! tava suprabhātam || (VSu 17) धाटीषु ते विहगराज-मृगाऽधिराज- नागाऽधिराज-गजराज-हयाऽधिराजाः । स्व-स्वा-ऽधिकार-महिमा-ऽऽदिकम् अर्थयन्ते श्रीवेङ्कटाचल-पते! तव सुप्रभातम् ॥

During Your journeys of conquest, the lord of birds & the lord of beasts & the lord of snakes & the lord of elephants & the lord of horses all seek to advance their respective glory in fulfilling their rights and duties to You: O Lord of the sacred mountain wealth-weaving, sin-cleaving Venkatam, a blessed morning unto You!

This verse serves as a simple illustration of the “layer-cake” model of exegesis that I introduced in my posting on verse I.14 of the Śrīmad-Bhagavad-Gītā (I need to resume that series of posts soon!). As a quick recap:

Layer 1: The plain meaning of the text

Layer 2: Additional meanings, whether due to paronomasia (śleṣa) or suggestion (dhvani) or the textual context (prakaraṇa)

Layer 3: The interaction and harmonization (samanvaya) of the multiple meanings extracted from the text—or as I described it in the post on the Gītā, establishing robustness to interpretive perturbation

Layer 4: The deepest layer of meaning, pointing to some kind of cosmic insight (gūḍhârtha)

Layer 1

The Layer 1 meaning of this verse is visible in the translation above: simple and straightforward, and might even make us wonder if there is anything else going here at all.

Layer 2

Complications arise when we realize the word dhāṭī has two different meanings:

It can mean “conquest” or “attack”. In this case, we would understand the lords of the various species of creatures to be actual deities themselves, like Garuḍa the king of birds, Airāvata the king of elephants, and so on.

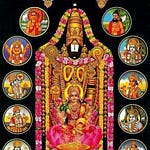

It can also refer, by extension, to the public processions of the utsava-mūrti (portable iconic) form of Lord Śrīnivāsa, who is known as Lord Malayappa Swāmī.1 In this case, the lords of the creatures refer to the specific vāhanas or zoomorphic vehicles on which the utsava-mūrti is carried through the town. Different animal vāhanas are used to carry the Lord with His consorts Śrīdevī and Bhūdevī on different days during major festivals like the Brahmôtsava and Vasantôtsava.

Layer 3

Of course, we should not insist on separating these two meanings too much.

After all, triumphal processions of the Divine are indeed like military expeditions: the Divine Couple leave their sanctified temple homes and come out, accompanied by their hosts of terrestrial and celestial attendants, on our road and by our houses. The display of Their sacred sanctifying presence defeats any evil and any impurity that may cling to us and prevent us from enjoying Them fully.

At the same time, it is also true that the military expeditions of the Lord, defeating the enemies of His devotees, are also triumphal processions in a cosmic sense. After all, did the Lord really need to climb onto Garuḍa and fly in person to save the elephant Gajendra, when He could have simply obliterated the very existence of the offending crocodile with His slightest passing thought? These displays of His martial might are really meant to soothe us, to help us comprehend His infinite power in terms that we can understand.

Ultimately, therefore, there is only one real meaning to the word dhāṭī, thus reconciling potential conflicts between the two Layer-2 meanings.

Layer 4

If we then scale up this insight to the cosmic level, we can come to see the entire universe as a triumphal procession of the Lord: everything that was, is and will be is a līlā, an act of free play for the Divine.

Play is serious stuff

To be very clear, this does not mean that everything is trivial or random. A game of cricket has rules for the players to abide by; a theatrical production has specific roles and lines and expressions for the actors to perform; our universe too has laws that govern its evolution. Nobody would suggest that an India–Australia Cricket World Cup final is not a serious event, just because it’s a sports match. And even outside the sports arena, we too are governed by various kinds of rules, whether or not we abide by them or try to cheat the game. (Free will is still very much a part of this game!)

The key word for all of this is adhikāra, a profoundly rich word in Sanskrit discourse that combines the concepts of “right” and “responsibility”. Only the goalkeeper in soccer has the adhikāra to handle the ball with his hands; every citizen in a democracy has the adhikāra to vote for their choice of political representative, and so on. (Especially in the latter case, people sometimes divorce the right to cast a vote from the civic responsibility to vote sensibly. In the Sanskritic view, however, choosing not to vote at all—as opposed to voting “None Of The Above”—would mean a failure to fulfill one’s adhikāra.)

Divine and human adhikāra

In the case of the various servants of the Divine Couple, they actively seek these opportunities to fulfill their adhikāra to be of service to Them. It is like a friendly competition between them, to show the depth of their love and attachment to the Divine. I emphasize the “friendly”, because where else would an eagle and a snake—mortal enemies—or a lion and an elephant—also mortal enemies—still get along together? It is their personal devotion to the Divine, together with their recognition of others as also being parama-bhaktas (supreme devotees), that allows for this genuine camaraderie.

Finally, note that none of them is seeking to usurp the other's position. Rather, each seeks to fulfill his own adhikāra to the best and fullest extent possible, and in doing so glorifies the Divine Duo.

Free to serve

The lesson for us all is clear: we should seek to fulfill our adhikāra to the best and fullest, in a manner that glorifies the Divine in both Their worldly displays and in Their cosmic displays. In the modern world, this does not necessarily have to mean a full-blown defense of traditionalist modes of being. Rather:

Fulfilling our adhikāra is fundamentally a process of self-discovery: learning to identify one’s gifts and one’s calling, and then finding ways to live out one’s calling in harmony with one’s obligations and desires—and doing all this ultimately with the desire to serve the purposes of the Divine!

The story of the squirrel who helped the vānaras build a bridge across the ocean to Laṅkā is most apt here: All we can do is carry a tiny pebble—but if we do that correctly, that is all that is needed. Ultimately, even the most colossal boulders carried by the greatest of the vānaras is no different in significance to the Divine than the squirrel’s tiny pebble—what matters is that both creatures were offering the absolute maximum that each could for the Divine.

|| Śrī-Padmāvatī-nāyikā-sameta-Śrī-Śrīnivāsa-parabrahmaṇe namaḥ ||

Interestingly enough, the older utsava-mūrti is known as Ugra (“fierce”) Śrīnivasa Swāmī. At some time, perhaps during Prativādi Bhayaṅkara Aṇṇan Swāmī’s lifetime itself, the self-manifested (svayaṃ-vyakta) of Lord Malayappa Swāmī was discovered at a site (today known as Malayappa Kōṇa), and Lord Śrīnivāsa Himself appeared in a devotee’s dream, instructing the priests to use Malayappa Swāmī for the processional function outside the temple due to His more benign nature being better suited to the current epoch. Ugra Śrīnivāsa Swāmī was retired to the sanctum sanctorum where He resides till today, standing alongside the dhruva-bera (the large, immovable icon) of Lord Śrīnivāsa and the kautuka-bera (small icon used in worship) of Bhoga Śrīnivāsa.

Share this post