Last time we saw the magnificence of the hills upon which Lord Śrīnivāsa rests. This time, we will see the cosmic significance of these hills.

sevā-parāḥ Śiva-Surêśa-Kṛśānu-Dharma- Rakṣô-Ambunātha-Pavamāna-Dhanâ-adhināthāḥ | baddhâ-añjali-pravilasan-nija-śīrṣa-deśāḥ Śrī-Veṅkaṭâcala-pate! tava suprabhātam || (VSu 16) सेवा-पराः शिव-सुरेश-कृशानु-धर्म- रक्षो-ऽम्बुनाथ-पवमान-धना-ऽऽधिनाथाः । बद्धा-ऽञ्जलि-प्रविलसन्-निज-शीर्ष-देशाः श्रीवेङ्कटाचल-पते! तव सुप्रभातम् ॥

Intent upon serving You are the Lords of the Eight Directions: Śiva Indra, chief of the gods Agni, celestial archer Yama, lord of Dharma Nirṛti, the demon Varuṇa, lord of the waters Vāyu, the purifier Kubera, lord of wealth their heads adorned by their hands pressed together in the añjali-mudrā of worship: O Lord of the sacred mountain wealth-weaving, sin-cleaving Veṅkaṭam, a blessed morning unto You!

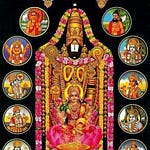

The Eight Guardians

In this verse, we have the aṣṭa-dikpālas, the Guardians of the Eight Directions, congregating at Tirupati to worship Lord Śrīnivāsa in the morning. While there are some slight variations in the list, let’s look at them again, in the order depicted here:1

The north-east is governed by Īśāna, a form of Śiva associated with knowledge. (It is therefore also called the aiśānī direction.)

The east is governed by Indra, the lord of heaven. (It is therefore also called the aindrī direction.)

The south-east is governed by Agni, the lord of fire. (It is therefore also called the āgneyī direction.)

The south is governed by Yama, the lord of the underworld and of dharma, order. (It is therefore also called the yāmyā direction.)

The south-west is governed by Nirṛti, a daitya associated with chaos (literally, lack of ṛta or order). (It is therefore also called the nairṛtī direction.)

The west is governed by Varuṇa, the lord of water. (It is therefore also called the vāruṇī direction.)

The north-west is governed by Vāyu, lord of wind. (It is therefore also called the vāyavī direction.)

The north is governed by Kubera, the lord of 9 different kinds of wealth.2 (It is therefore also called the kauberī direction.)

Compass directions

There are two important things to reflect upon here.

Directionality

The first is the order of the list. If you follow the sequence of directions, it proceeds neatly in clockwise order (seen from above): the exact sequence in which we traverse the directions when circumambulating the temple deity with our right sides facing the deity constantly (pradakṣiṇa). It is thus as if the whole universe is circumambulating Lord Śrīnivāsa in the morning.

But also note the starting point of the directions. While we would normally expect the sequence to begin with one of the cardinal points, most often East in the Indian context, here we begin with the north-east and conclude with the north. The answer to this lies, I think, in the specific domains governed by these dikpālas: Śiva as Īśāna, who protects the north-east, governs knowledge; Kubera, who protects the north, governs wealth. In effect, by beginning our journey with knowledge of the true potency of Lord Śrīnivāsa and Padmāvatī Tāyār, we are guaranteed to conclude it with true prosperity—both this-worldly and other-worldly.

“North of what, precisely?”

The second key point is a bit more subtle: The lords of the eight directions are all posted at eight different points on the compass. What, then, is the best way of thinking about the central point from which they emanate?

The center of the compass is the origin of the whole cosmic coordinate system; the axis of circumambulation is the central axis around which the whole universe revolves. This is the centrality of Lord Śrīnivāsa and Padmāvatī Tāyār!

To toss in a fancy term here, the Lord is the axis mundi, the center around which the world orbits. This concept is particularly important here, because in Hindu cosmology, it is Mount Meru that is the central mountain or axis mundi. But in our context, it is Lord Śrīnivāsa, and by extension the hills of Tirupati, that plays this role. (The implicit importance of the hills of Tirupati in this verse thus connects it to verse 15, where the hills were explicitly celebrated.)

The importance of posture

The description of the dik-pālas is quite elaborate, with their heads are adorned by their hands pressed together in a namaste gesture (properly known as the añjali-mudrā). Why is so much detail given to this?

Because this is the exact pose that the Blessed Lord Kṛṣṇa insists that the milkmaids adopt when they beseech Him to get their clothes back! It is thus the ultimate gesture of egoless surrender to the Divine: with the knowledge that all of us are, effectively, naked inside and outside in the face of Divine omniscience and omnipotence; but also with full trust (śraddhā) and confidence (mahā-viśvāsa) that the Divine Couple will shelter us and take care of us.

Swāmī Deśikar has beautifully described this in his Gopāla-Vimśati’s penultimate dhyāna-śloka (verse designed for visualization and contemplation):

vāso hṛtvā Dinakara-sutā-sannidhau vallavīnāṃ līlā-smero jayati lalitām āsthitaḥ kunda-śākhām | sa-vrīḍābhis tad-anu vasane tābhir abhyarthyamāne Kāmī kaś cit kara-kamalayor añjaliṃ yācamānaḥ || (GV 19)

He steals the clothes of the milkmaids on the banks of the Yamunā (daughter of the Sun) and sits on the jasmine tree’s elegant branch, smiling playfully as He is beseeched by them bashfully seeking their clothes back their lotus-hands pressed in the añjali-mudrā: That indescribable, playful, Lord is victorious!

|| Śrī-Padmāvatī-nāyikā-sameta-Śrī-Śrīnivāsa-parabrahmaṇe namaḥ ||

The Amara-kośa lexicon has a tightly interconnected set of verses that list, in order, the the eight dik-pālas, the governing astrological planet (graha) for each direction, the celestial elephant (dig-gaja), and the elephant’s consort. I’ll leave the verses untranslated since they are just lists of names.

Indro (E), Vahniḥ (SE), Pitṛ-patir (S), Nairṛto (SW), Varuṇo (W), Marut (NW) | Kubera (N), Īśaḥ (NE) patayaḥ pūrvâ-ādīnāṃ diśāṃ kramāt || Raviḥ (E), Śukro (SE), Mahī-sūnuḥ (S), Svarbhānur (SW), Bhānujo (W), Vidhuḥ (NW) | Budho (N), Bṛhaspatiś (NE) cê iti: diśāṃ caîva tathā grahāḥ || Airāvataḥ (E), Puṇḍarīko (SE), Vāmanaḥ (S), Kumudo (SW), Añjanaḥ (W) | Puṣpadantaḥ (NW), Sārvabhaumaḥ (N), Supratīkaś (NE) ca: dig-gajāḥ || kariṇyo: Abhramu (E)-Kapilā (SE)-Piṅgalā (S)-Anupamāḥ (SW) kramāt | Tāmra-karṇī (W), Śubhra-dantī (NW) câ, Añjanā (N) câ, Añjanāvatī (NE) ||

The Amara-kośa lexicon lists the 9 treasures of Kubera as follows:

mahā-padmaś ca padmaś ca saṅkho makara-kacchapau | mukunda-kunda-nīlāś ca kharvaś ca: nidhayo nava || (AK I.1.166)

The literal translation of the verse reads as follows:

A great lotus and a lotus, A conch, A crocodile and a tortoise, Quicksilver, jasmine, sapphire, and a kharva: These are the Nine Treasures.

Presumably these items have to be interpreted symbolically, or refer to rare kinds of gems or something similar. With the last word in particular, kharva, I genuinely don’t know to translate it: it can mean “dwarf”, “baked-clay vessel”, or an extremely large number, some say 1010 and others say 1037.

Share this post