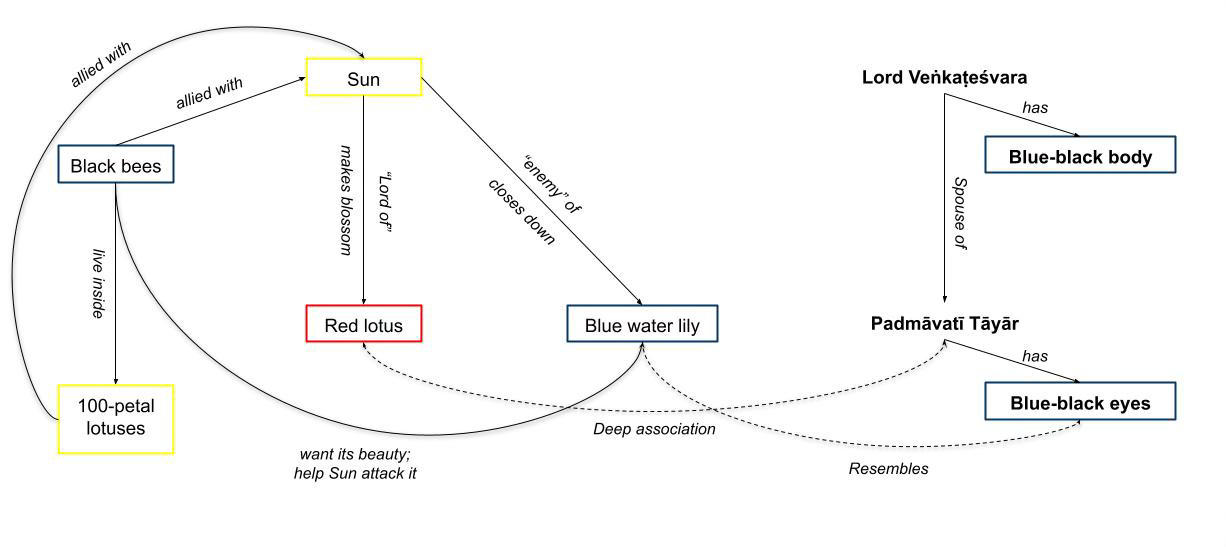

Today’s verse marks the end of the first section of the Śrī Veṅkaṭeśa Suprabhātam, as characterized by the refrain of each verse. It integrates the theme of conflict from verse 11 with the theme of bees and lotuses that we saw in verse 10, but we will see how it has its own intricate poetic beauty as well.

Padmêśa-mitra-śata-patra-gatâ-’li-vargāḥ hartuṃ śriyaṃ kuvalayasya nijâ-’ṅga-lakṣmyā | bherī-ninādam iva bibhrati tīvra-nādaṃ Śeṣâdri-śekhara-vibho! tava suprabhātam || (VSu 12) पद्मेश-मित्र-शतपत्र-गता-ऽलि-वर्गाः हर्तुं श्रियं कुवलयस्य निजा-ऽङ्ग-लक्ष्म्या । भेरी-निनादम् इव बिभ्रति तीव्र-नादं शेषाद्रि-शेखर-विभो ! तव सुप्रभातम् ॥

Ranks of black bees residing in hundred-petalled lotuses (allies of the lord of lotuses: the Sun, and favorites of the Lord of the Lotus-lady Padmāvatī) buzz sharply, like thundering wardrums, in order to snatch away the beauty of the water-lilies with their own bodies’ beauty: O all-pervading Almighty atop Seshadri, a blessed morning unto You!

Flowers, flowers everywhere

This verse is very dense with flower imagery: we have red lotuses (padma in the neuter gender), hundred-petalled golden-white lotuses (śatapatra), and blue waterlilies (kuvalaya). The key ideas to keep in mind here are the following conventions of Sanskrit poetry:

lotuses blossom in the daytime, thus associating them with the Sun

golden lotuses, with their multifarious petals, also bear a color resemblance to the Sun

waterlilies blossom at night, and hence have an antagonistic relationship with the Sun

waterlilies, bees, and the Lord all have dark blue–black (nīla, śyāma) bodies,

The Divine Couple’s eyes, and by extension Their gracious glances, are often described as resembling blue lotuses or blue waterlilies1

the Divine Couple’s palms are pink/red like red lotuses

We can use this to make sense of the surface imagery of the verse, before getting into deeper theological interpretations.

The war of the bees and the lilies

Let’s start by recollecting the natural scene in non-poetic fashion: Dawn has broken, the Sun has climbed above the horizon, lotuses are blossoming, and bees are buzzing. The additional temporal development outlined in this verse is the closing-up of the waterlilies: it is now bright enough, and night has receded enough, that the lilies are shutting up shop for the day (literally).

Śrī PB Aṇṇan Swāmī’s poetic genius lies in connecting the buzzing of the bees with the closing-up of the waterlilies through a theme of conquest and the spoils of war. This is based on the shared blue-black beauty (śrī, lakṣmī) of the bees and the lilies, which prompts the bees to try to capture the lilies’ beauty for themselves. This raid by the bees is a sideshow to the overall battle between the Sun and the lilies, and so the bees are portrayed as an ally (mitra) of the Sun. Their sharp buzzing is thus reminiscent of the kettle-drums (bherī) that warring parties would deploy prior to the outbreak of outright conflict.2

Now, to be clear, the bees aren’t buzzing in order to actually capture the lilies’ beauty; in fact, the bees are described as already having a beauty of their own (nijâṅga-lakṣmī). But Aṇṇan Swāmī has supplied this beautiful poetic fancy to describe their actions and to inject an extra element of beauty and meaningfulness into the world. 3

“Words are all I have”

Before we get into the theological interpretations of this rich verse, I want to dwell upon some specific choices of words that Aṇṇan Swāmī has made here. These choices connect this verse to previous ones, generate suggestive meanings, and also enable the deeper theological meanings that we will turn to shortly.

“Lotus(-lady)-lord”

Let’s start with the very first word itself: Padmêśa. It is a compound word (samasta-pada, to use the Sanskrit grammatical terminology), but what are its constituent elements?

One obvious choice is padma + īśa, where the first word is in the neuter and hence means “lotus”. The word īśa can mean “controller, director”, and hence “lord”. Taken together, the word means “the lord of lotuses”, and hence refers to the Sun (who makes lotuses bloom, and hence “commands” them). This is in keeping with the martial theme we have already seen, where the Sun is the Lord and Commander of the Forces of Daylight, so to speak.

A different choice is to take the feminine form of the first word, to get Padmā. This is of course Padmāvatī Tāyār, the Lotus-lady who sits on a fully bloomed red lotus (Alar-mēl maṅgai in Tamil, Ala-mēlu maṅgā in Telugu). In this situation, īśa can be interpreted in two ways: either as the “Supreme Lord”, or also simply as “husband”. In either case, Padmêśa now refers to Lord Veṅkaṭeśvara, who is the Supreme Lord of the Universe along with Padmāvatī Tāyār, and who is also simply Padmāvatī’s Husband.

This dual interpretation itself tells us that we should be looking for theological interpretations for the overall meaning and symbolism of the verse.

“Friend, ally, Sun”

The second word, mitra, can also be interpreted in a number of ways:

In a political context, mitra means “ally”.4 This is in keeping with the martial interpretation of the verse we have seen so far. But who is the Sun’s ally here?

The most natural thing grammatically would be to link this to the following word, śatapatra. These large golden lotuses can be thought of as the Sun’s allies, as they open up on his command and launch their bee-bombers to annihilate the hapless lilies.

But given that the golden lotuses are also lotuses, and given that the Sun has already been described as the “lord of lotuses”, it is strange to then call them his allies. After all, we normally associate the term “ally” with another sovereign party who is choosing to align themselves with someone, and not with a vassal who has little say in the matter. In this case, the natural allies for the Sun are the bees who live (or who were trapped inside) the lotuses. Perhaps they will act as light cavalry for the Sun, launching harassing attacks on the waterlilies as they flee from the sunlight.

Mitra can also refer to the Vedic solar deity, who is the lord of friendships and of contracts that bind us in alliances with our fellow humans. Mitra is in some ways a lord of openings: He is the first deity invoked at the beginning of the Taittirīya Upaniṣad5 and He is also specifically worshipped in the upasthāna portion of the mandatory dawn prayer (prātaḥ sandhyā). We can either take this interpretation to simply hint at solar worship at dawn (as is ongoing in the verse), or as a reinforcement of the solar interpretation of Padmêśa.

Finally, and most obviously, mitra simply means “friend” in Sanskrit, just as it does in modern Indian languages. The bees may be the Sun’s allies, but they are Lord Veṅkaṭeśvara’s friends. The Lord has no need of allies per se, but in His infinite graciousness (sauśīlya) and accessibility (saulabhya), He is Friend to all those who turn to Him in friendship.

Beauty and Beauty

There are two words used to mean “beauty” here: śriyam and laksmyā. And while both words can be used to mean “beauty” in general in Sanskrit, it is no coincidence that both of them are names for the Supreme Goddess Herself. In fact, Her “proper” name, so to speak, is declared by Swāmī Āḷavandār in the Catuḥślokī to be «Śrī» itself:

«Śrīr» ity eva ca nāma te, Bhagavati! (CŚ 1d)

And Your sacred, true name o Goddess! is Śrī.

But aside from these two being names of the Supreme Goddess, we also see that they are used with different case-endings:

śriyaṃ is the accusative (dvitīyā) form of śrī, which in this case is used to indicate that this śrī is the object (karman) of some agent’s actions. On the surface level, this is the waterlilies’ beauty that is the objective of the bees’ buzzing. But at a deeper level, this has a cosmic significance that we will need to explore.

lakṣmyā is the instrumental (tṛtīyā) form of lakṣmī, which is used to mark this lakṣmī as a means to accomplishing something. This has a plain meaning in reference to the beauty of the buzzing bees, but this is also a matter of cosmic significance as well.

Sound effects

Continuing with the theme of “sharp sounds” from verse 11, this time we have the sharp sounds of the buzzing bees. The connection between the two verses is heightened by the repetition of the word tīvra in both.

Also notice the repetition of the sounds nādam in the words ninādam and tīvra-nādam, as well as the repetition of labial bhs (and one v) in close proximity with buzzing rs in the third line. This is a sonic reminder of the name bhramara for bees, itself an onomatopoetic representation of the sounds made by these creatures.

Some theological lessons

The multiple meanings communicated by the different words in this verse should already be hinting to us the broad contours of the theological interpretations of the verse as a whole.

From lotuses and suns to the Lotus-lady and the Lord

The first obvious interpretive move is reflected in the two interpretations of the word padmêśa seen above: instead of talking about lotuses and suns, we should instead be talking about the Lotus-lady, Padmāvatī Tāyār, and Her beloved, Lord Śrīnivāsa.

This re-injection of the divinity into a seemingly charming nature scene has two effects:

We now need to build up an interpretation of the verse where Lord Śrīnivāsa and Lady Padmāvatī Tāyār play a prominent role, like the sun in the previous.

We also learn an important lesson about language and the Divine: All words ultimately refer to the Divine in some way or the other. And this is paralleled by another important lesson about all of reality and the Divine: All that exists is pervaded and grounded in the Divine.

This second lesson also connects to the interpretation of (m/M)itra as the solar deity: In the same prātaḥ-sandhyā dawn prayer, after reciting the upasthāna verses to Mitra, Śrīvaiṣṇavas then recite a beautiful and intricate verse designed for contemplation (beginning with the words dhyeyaḥ sadā) that reveals the inner divinity within the solar orb to be Śrīman-Nārāyaṇa Himself.

An implicit comparison

One last point here: the use of this single word, padmêśa, to describe both the Sun as the “lord of lotuses” and Lord Veṅkaṭeśvara as the eternal spouse of Padmāvatī Tāyār, sets up an implicit simile (vyaṅgyôpamā) between the two. We might start by saying that, just as the Sun makes lotuses bloom, so too does Lord Veṅkaṭeśvara make Padmāvatī Tāyār blossom with delight.

But upon further reflection, we realize that we need to flip the comparison around: When we see lotuses blooming when kissed by the Sun’s rays at dawn, we are in fact seeing a tiny glimpse of the eternal, ever-renewing blossoming bliss that Padmāvatī Tāyār experiences in Her eternal, inseparable companionship with the Cosmic Sun, Lord Śrīnivāsa.

Thus, all around us are signs of the deep pervasion of the cosmos by the Divine, available to us if we but train ourselves to see the universe in this (Divine) light.

The lesson of the lilies

We haven’t talked much about the waterlilies so far, but we can find the presence of the Divine here as well. For one, the verse explicitly states that the Supreme Lady also graces the waterlily (śriyaṃ kuvalayasya). In conjunction with a general awareness of Sanskrit devotional poetry, in which the Lord is described as having a waterlily–blue-black body and the Lotus-lady is said to have waterlily–blue-black eyes, we can expand our interpretation as follows:

The Lord’s body’s beauty is in fact indescribable, as is the beauty of the Lotus-lady’s eyes.

We can enjoy a small sliver of this infinite beauty when we relish the beauty of waterlilies.

Just as waterlilies blossom at night in the presence of the moon, so too does the beauty of the Lord’s body blossom in the cosmic moonlight of Mahālakṣmī’s visage.

But while the beauty of lotuses and lilies may wax and wane, the eternal beauty of Lord Veṅkaṭeśvara and Padmāvatī Tāyār—especially in light of Their eternal companionship—is a cosmic constant.

From alliances to friendship

We can now, finally, turn to the lessons of the bees. We can treat them both as a positive example to be emulated by us, as well as a negative example to be avoided.

Bees as positive example

This positive interpretation hinges on parsing the word Padmêśa-mitra as a tatpuruṣa compound: Padmêśasya mitrāṇi, “friends of the Spouse of Padmāvatī”.

On this analysis, we see that there is a relation of friendship between the bees and Lord Veṅkaṭeśvara. This is no mere political alliance that crystallizes and dissolves with the vicissitudes of time: this is an act of graciousness bestowed upon the bees by Lord Śrīnivāsa. Why is this so? Because of the bees’ devotion to the lotuses, which, as we have seen above, are a stand-in for the Lotus-lady, Padmāvatī Tāyār. The Lord loves those who come to Him through His eternal companion, the Lotus-lady.

The bees’ service to the Divine Couple isn’t limited to percussion. They are willing to go to war, to put their limbs on the line, to defend Her from the waterlilies. All of this should draw our minds to the vānaras: They were willing to fight for Lord Rāma to help restore His śrī—His wife Sītā—from the clutches of the demon-king Rāvaṇa (who, like the waterlily, preferred the night). No wonder their king Sugrīva earned both the allyship and the friendship of Lord Rāma!

Bees as negative example

If we analyze the compound Padmêśa-mitra as a bahuvrīhi compound, yielding Padmêśaḥ mitraṃ yeṣāṃ te (“those to whom the Spouse of Padmāvatī is a friend”), we open the doors to a different, and this time a negative, interpretation. The Lord is still willing to be a friend to the bees, but the bees are so fixated on the beauty of the waterlilies that they don’t pay heed to Him.

In this version of the story, the waterlilies are closing down because it is now dawn—this is normal for them. But the blue-black iridescent bees are trying to compete with the blue waterlilies regardless, not realizing that they don’t actually need to: their limbs are already adorned with beauty (lakṣmī) that resembles the Lord’s body. Thus, not realizing that they are already blessed, the bees are trying to overreach.

On this interpretation, it is the bees who are behaving in a Rāvaṇa-like manner, trying to conquer Mahālakṣmī by force, not realizing that:

they cannot in fact take away the beauty of the waterlilies because that is a whole separate natural process—they are doomed to failure;

Mahālakṣmī is already with them in abundance in the form of their beautiful blue-black bodies that resemble Her eyes and His body; and

the Lord is already more than open to being their friend, if they would but turn to Him once.

This interpretation of the bees is perhaps a better analogy for the behavior of people trapped on the materialist treadmill, where there is always a promotion with a bigger salary or a fancier house or a flashier car that “needs” to be bought. But it might also effectively serve as a warning to what we might call “spiritual materialists” as well: to people who take undue pride in extravagant and ostentatious displays of their supposed religious piety.

The point here is that everything (and everybody) in the cosmos has their own intrinsic beauty and their own intrinsic role in serving the Divine Couple, and that trying to usurp someone else’s position out of a false sense of competition is pointless—but at the same time, the friendship of the Lord is open and available to one and all.

The heart of the matter: Beauty and the Beauty

Let us wrap up this analysis by finally turning to the cosmic significance of the words śriyam and lakṣmyā. Both the waterlilies and the bees are not just beautiful, but literally blessed with the presence of the Supreme Goddess Herself. Indeed, it would be even more accurate to state that everything in this world that is beautiful is beautiful because of Mahālakṣmī’s presence.6 And we can extend this even further, to the Divine Couple Themselves: The Lord’s blue-black body is beautiful because—like the waterlilies and the bees that resemble it—it is blessed with Her presence.

And now let us turn to the specific case-endings and their significance. Mahālakṣmī is both the object (karman) and the instrument (karaṇa)—not just of the bees’ behavior, but of the Lord.7 Given that the Ultimate Agent, the Kartṛ, is the Lord Himself, it therefore stands to reason that His most desired end is the Goddess Herself. And the instrument He uses to obtain His most desired end is Mahālakṣmī Herself!8

In non-technical language, Lord Veṅkaṭeśvara is trying to charm Padmāvatī Tāyār through His beauty—but that beauty is in fact Tāyār Herself! He is trying to reach Her through Her—and of course He is successful, because (a) She never lets anyone down, and (b) She is always already inseparable from Him.

This is exactly the relation we should have to the Divya Dampati as devotees ourselves: we must aspire to reach Them through Them. The typical phrasing of this in Sanskrit is that the Divya Dampati are both the upeya (the destination, the goal) and the upāya (the path, the means).

Thus, the charming surface-level imagery of bees and lilies yields a beautiful image of the eternal bond between Lord Veṅkaṭeśvara and Padmāvatī Tāyār, which in turn presents us with a lesson on how we should approach the Divine.

|| Śrī-Padmāvatī-nāyikā-sameta-Śrī-Śrīnivāsa-parabrahmaṇe namaḥ ||

My all-time favorite example of this cluster of imagery is the grand opening verse (Lakṣmī-netrôtpala-śrī) of Swāmī Vedânta Deśika’s Tattva-muktā-kalāpa, in which he weaves in the dark beauty of Lakṣmī’s eyes, the dark beauty of the Lord’s body, and swarms of bees—all while subtly hinting at the 5-chaptered architecture of the 500-verse philosophical masterpiece! Indeed, I wonder if this opening verse was on Śrī Aṇṇan Swāmī’s mind when he composed this verse of the Śrī Veṅkaṭeśa Suprabhātam, because here too the words Lakṣmī and śrī are repeated.

The most famous example of this is verse I.13 of the Bhagavad-Gītā, in which the Kaurava army pounds its kettledrums in a failed effort to intimidate the Pāṇḍavas. This verse from the Gītā too may have been on Aṇṇan Swāmī’s mind.

Such a “fantastic ætiology” is known in Sanskrit literary theory as phalôtprekṣā: a poetic imagination of a fanciful effect of an action.

Thus, the first two sections of the Pañcatantra are known as the Mitra-bheda and the Mitra-lābha. Often translated as “Dissent among Friends” and “Making Friends”, the two chapters are better thought of as “Splitting Allies Apart” and “Obtaining Allies”.

This is the famous śānti-mantra that begins with an invocation to a triad of Vedic solar deities whose worship extends far back into a common Hindu–Zoroastrian past:

śáṃ no Mitráḥ śaṃ Váruṇaḥ / śáṃ no bhavatv Aryamā́ |

Auspicious be Mitra to us, auspicious be Varuṇa; Auspicious be Aryaman to us.

As Vedânta Deśikar describes Her in the first verse of the Śrī Stuti, She is maṅgalaṃ maṅgalānām.

Indeed, the definition of karman in the Pāṇinian system is kartur īpsitatamaṃ karma (PāAA I.4.49), “the object is that which is most desired by the agent”.

Again with Pāṇini, the instrument (karaṇa) is defined as sādhakatamaṃ karaṇam (PāAA I.4.42), “the instrument is that which is the most efficient effector (of the action)”.

Share this post