Welcome back! After a bit of a hiatus, let us recommence our journey through the Śrī Veṅkaṭeśa Suprabhātam. We are now into the second third of the hymn, and find ourselves today with a verse that is truly distinguished by its merger of sound and sense symbolism:

yoṣā-gaṇena vara-dadhni vimathyamāne ghoṣâ-’’layeṣu dadhi-manthana-tīvra-ghoṣāḥ | roṣāt kaliṃ vidadhate kakubhaś ca kumbhāḥ Śeṣâdri-śekhara-vibho! tava suprabhātam || (VSu 11) योषा-गणेन वर-दध्नि विमथ्यमाने घोषा-ऽऽलयेषु दधि-मन्थन-तीव्र-घोषाः । रोषात् कलिं विदधते ककुभश्च कुम्भाः शेषाद्रि-शेखर-विभो ! तव सुप्रभातम् ॥

As the young milkmaids churn milk into the choicest curds in the hamlets of the cowherds, the sharp sounds of their churning-sticks is as if the pots are quarreling incessantly in all directions: O all-pervading Almighty atop Seshadri, a blessed morning unto You!

Pastoral sketches

This verse strongly evokes the atmosphere of Āṇḍāḷ’s Tirup-pāvai, set in Āyarpāḍi (a Tamilized version of the Gokula of Lord Kṛṣṇa’s childhood), filled with milkmaids and cowherds. Similar imagery is evoked in multiple pāsurams from the Tirup-pavai; just one example should suffice for now:

Āycciyar # mattināl ōsai paḍutta tayir-aravam kēṭṭilaiyo? (TP 7de) ஆய்ச்சியர் # மத்தினால் ஓசை படுத்த தயிர் அரவம் கேட்டிலையோ

Do you not hear the sound of curds being churned by the milkmaids of Āyarpāḍi with their churners?

Son et sens

The sounds of the jeweled bangles of the milkmaids jingling, along with the sounds of the churning-sticks with the pots, are resounding in all quarters in order to wake people up. The repetitive nature of the work and the harshness of the sounds is portrayed in the verse by the repetition both of sounds (oṣā over and over in various words; various words from dadh and math) as well as of entire words (dadh(n)i and ghoṣa in particular). And each of these repetitions has its own special features:

The repeated sounds have very different sonic textures, with different suggestions (śabda):

The open, resonant oṣā cluster with the sharp sibilant in the middle sounds like the continuous jingling and clattering of the milkmaids’ bangles.

This might just be me being overly fanciful, but this sequence also reminds me of Uṣas, the Vedic goddess of dawn. Her appearance would of course be highly appropriate in the context of a suprabhātam work.

And of course, the oṣā sequence also resonates with Śeṣâ(dri) as well. This kind of second-syllable rhyme is actually a classic feature of Tamil poetry, where the phenomenon is known as yĕdugai.

Further strengthening the “Tamilness” of this verse, the line-internal yĕdugai in the second line between the beginning and the end is also reminiscent of the quintessentially Tamil poetic form known as the nēr-isai vĕṇbā, in which this exact phenomenon can be noticed.

The dadh and ma(n)th sequences both end in flat, heavy, aspirated consonants, rather like the churning-sticks squelching in the pots.

The repeated words have very different semantics (artha):

One pair of repeated words shares the same core meaning: dadhi and dadhni both mean “curd”, albeit in different grammatical cases.

Another pair of repeated words has different meanings, so that it might be better to think of this as two separate words that happen to share the same sonic body: ghoṣa means both “noise” and “hamlet of cowherds”.

It is at this level of sound-and-sense that we truly see poetry starting to operate:1 sounds hint at certain meanings which then need to cohere with the broader meaning and context of the verse, which in turn create new opportunities to reassess the sounds of the verse. The fact that all of this is happening in a verse depicting a soundscape is all the more befitting!

From sound effects to salvation

In the Śrīvaiṣṇava tradition, there are profound symbolic meanings associated with the milkmaids of Āyarpāḍi and with the churning of milk into curd. These are elaborated upon at great length by the spiritual scholar–leaders of the community during the annual Tirup-pāvai exposition season in the month of Mārgazhi, so I will resist the temptation to dive clumsily into these deep waters. However, there are a few obvious theological connections that can be drawn here which I will foolhardily venture to state.

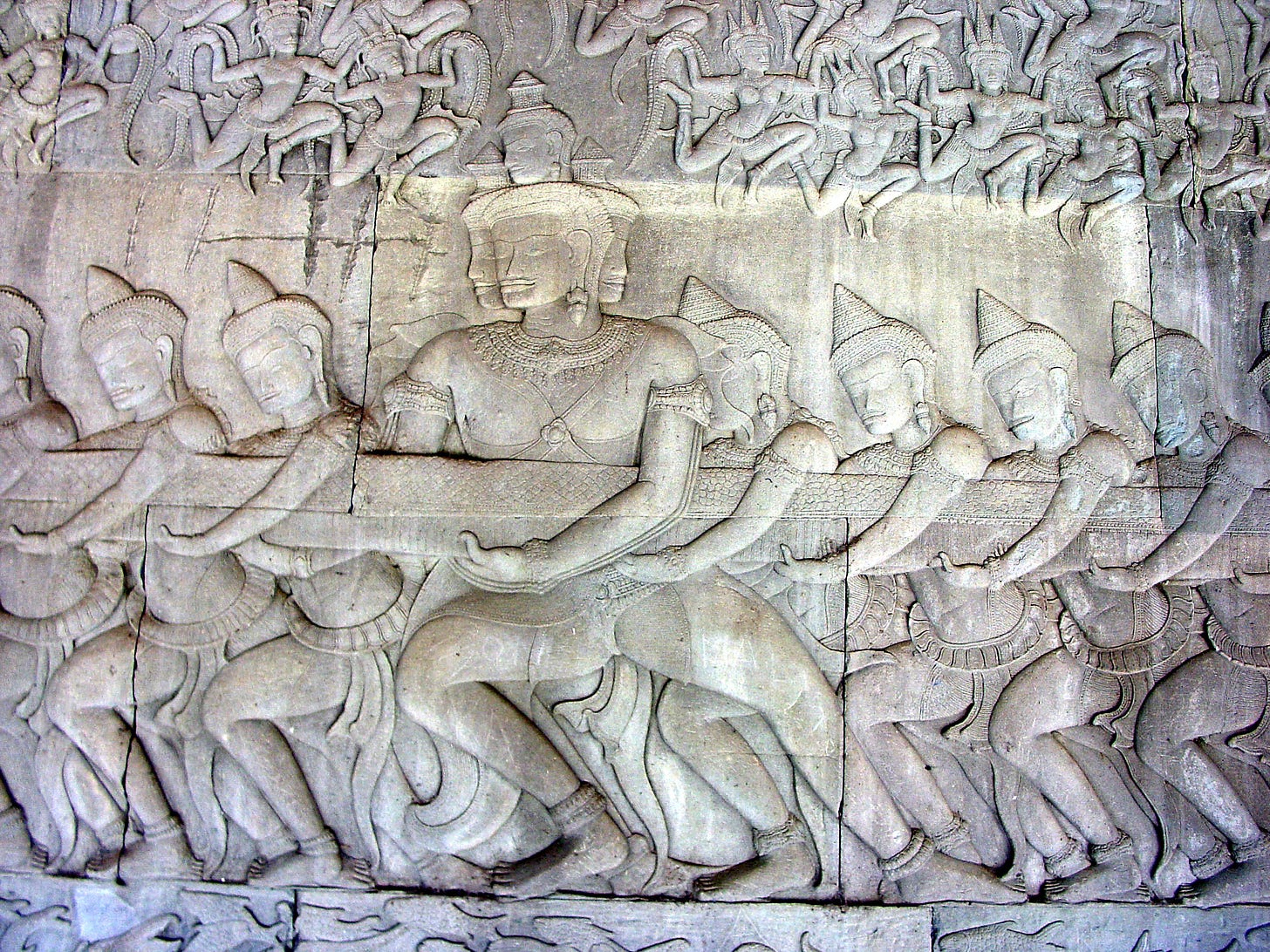

Connection 1: The churning and the Churning

The first is the obvious parallel between the churning of the milk by the milkmaids and the Churning of the Cosmic Ocean of Milk by the gods and anti-gods. The latter was not a peaceful process (the emergence of the Hālāhala poison, the conflict between the gods and the anti-gods over the possession of Amṛta, the immortality-bestowing ambrosia), but from it did emerge the Goddess Mahālakṣmī who is the most Beloved of Lord Śrīnivāsa.

We should similarly imagine that the milkmaids intend to make their curds a devotional offering to Lord Veṅkaṭeśvara, since the creamy curds represent, well, the crème de la crème of the milk they obtained.

Connection 2: The churning of the self

Building off this idea of the crème de la crème, we should also think about a personal, spiritual churning as well. It is not always a peaceful or painless process to undergo a spiritual transformation, but the end-goal should be for us to identify our best selves—and then offer that freely to Lord Veṅkaṭeśvara.

This is what makes this a good morning for the Lord, even though there is so much noise and commotion: the fact that we are bringing what is best in us to the Divine, and aspiring to use that in service of the Divine to make the world a better place.

Connection 3: The individual and the collective

The third is the collective and essentially social nature of Śrīvaiṣṇava devotional participation: The milkmaids are not alone, but are clustered together in groups (gaṇas). We see this especially clearly in Āṇḍāḷ’s Tirup-pāvai where she awakens multiple milkmaids over multiple verses, exhorting them to present themselves as a group to Lord Kṛṣṇa to wake Him up. This is an extremely important element of Śrīvaiṣṇava devotion practice: while salvation of the individual soul (jīvâtman) may be solitary, and while certain kinds of meditations can of course be solitary as well, people are also encouraged to worship the Divine in congregations (goṣṭhīs).

And as anybody who has ever worked out with a gym buddy or has tried to acquire new habits with an accountability partner knows only too well, this kind of congregational social support is vital for comforting, encouraging, and occasionally urging people along on personal transformations. Why should it be any different for a spiritual transformation?

|| Śrī-Padmāvatī-nāyikā-sameta-Śrī-Śrīnivāsa-parabrahmaṇe namaḥ ||

This is indeed how Bhāmaha defines literature at the very beginning of his Kāvyâlaṅkāra, one of the earliest texts in Sanskrit literary theory:

śabdâ-’rthau sahitau kāvyam (BhāKāA I.16a)

Literature is sound and sense conjoined.

This is where the word sāhitya for “literature” comes from: the harmonious conjoint effect of linguistic structures and their semanto-pragmatic effects on the reader.

Share this post