Ch. 1, Verses 15–16: The battle of the conches, part 3

The Pāṇḍavas respond to the Kaurava challenge

On this holy day of Ratha Saptamī, I seek to restart my postings of verses and commentaries from the Śrīmad -Bhagavad-Gītā. I began my sequence of posts on the same day a few years ago, so I think it is quite appropriate to re-commence on this day of all days.

When last I posted on this topic (almost two full years ago!), we saw the response of the Blessed Lord Kṛṣṇa and Arjuna to the blowing of the conches of the Kaurava army, led by Bhīṣma:

Ch. 1, Verse 14: The battle of the conches, part 2

After a far-too-long hiatus, let us continue our journey through the verses of the Śrīmad-Bhagavad-Gītā.

In that post, I had said I would talk a little more about the symbolism of the conch in a future post. That time has now come today!

The Pāṇḍava response, part 2: The Pāṇḍava siblings all together

After the grand description of the Blessed Lord Kṛṣṇa and Arjuna, we now get a glimpse of all the Pāṇḍava brothers, together with their conches. This is spread out across Verses I.15 and I.16 together:

Pāñcajanyaṃ Hṛṣīkeśo, Devadattaṃ Dhanañjayaḥ | Pauṇḍraṃ dadhmau mahā-śaṅkhaṃ Bhīma-karmā Vṛkôdaraḥ || Ananta-vijayaṃ rājā Kuntī-putro Yudhiṣṭhiraḥ | Nakulaḥ Sahadevaś ca Sughoṣa-Maṇipuṣpakau || (BhG I.15–16)

Kṛṣṇa Hṛṣīkeśa blew the conch named Pāñcajanya and Arjuna Dhanañjaya the conch named Devadatta; while wolf-bellied Bhīma of fell deeds blew the huge conch called Pauṇḍra. King Yudhiṣṭhira son of Kuntī blew the conch named Ananta-vijaya; while Nakula and Sahadeva blew their conches named Sughoṣa and Maṇipuṣpaka.

These verses are straightforward to understand, but the names and epithets used here are significant and worth examining closely. But before that, the conches!

Interlude: Why conches matter here

While we have talked about the blowing of conches for a while, we haven’t yet talked about why conches are significant in this context. If you have visited a Hindu temple, particularly one with a focus on Lord Viṣṇu or His avatāras like Lord Kṛṣṇa, you have likely seen conches depicted on the walls and with the deities; you may even have heard the priests blow the conches at particular times during certain rituals. What, then, is the underlying significance of the conch?

An exercise in creative etymology

Let’s start with the Sanskrit word for “conch”, śaṅkha (which also happens to be etymologically related to “conch”). In an exercise of creative etymologizing (inspired by the Nirukta tradition), we can attempt to analyze this word in terms of its constituent parts, and then try to synthesize those findings into a greater whole that adds resonances to the plain old meaning of the word.

[Analysis] The word śaṅkha is, strictly speaking, unanalyzable. However, if we let our creative juices flow, we can break it up into its two syllables śam and kha and then look at their meanings:

The word śam means “auspiciousness”, “tranquility”, “well-being”, “peace”, and so on. It is a key part of various śānti-mantras (prayers for peace).1

Treated as a word, kha actually has quite a wide range of meanings, of which the ones that are the most pertinent to us are “space / sky” (ākāśa), “heaven”, and “sense-organ” (indriya).2

[Synthesis] If we then re-assemble these two meanings together, we uncover two creative understandings of the word śaṅkha:

In an external sense, a śaṅkha is a means for purifying and pacifying space.

In an internal sense, a śaṅkha is a means for purifying and pacifying our sense-organs (i.e., our tools for perceiving the world).

This creative interpretation thus justifies the ritual use of the conch for worship: it purifies both external space as well as the internal space of the listeners.

This is seen in one of the verses of the Pañcāyudha-stotra dedicated to Pāñcajanya:

Viṣṇor mukhô-utthâ-anila-pūritasya yasya dhvanir dānava-darpa-hantā | taṃ Pāñcajanyaṃ śaśi-koṭi-śubhraṃ śaṅkhaṃ sadā ahaṃ śaraṇaṃ prapadye || (5AS 2)

Filled with the air blown from Lord Viṣṇu’s mouth, He thunders, slaying the pride of the demons. In that Pāñcajanya conch whiter than ten million moons do I eternally take refuge!

Crystallized spiritual alchemy

But why should a conch be able to do this at all? There are a variety of stories from the Purāṇas and other Hindu texts that provide mythological accounts for the sacred power of conches. Here, I want to propose yet another account:

The conch is, by its very nature, a crystallization of the alchemical transformation of spirituality, from the grossest of natures to the subtlest.

Let’s unpack that:

[Earth] A conch is made almost entirely of calcium carbonate, which is also found in limestone and marble. As such, a conch is a concrete manifestation of earth.

[Water] Though terrestrial in substance, conches are aquatic in origin, being created by sea snails. The well-known phenomenon of seashell resonance, in which you can “hear” the ocean (really your own blood-flow) by putting a seashell to your ear, only reinforces this connection between the conch and the sea.

[Fire] There are two connections between conches and fire, one general and one specific to one particular conch:

[General] As we blow a conch, the air gets compressed as it flows through the narrow, intricate passages of the conch. This increase in pressure naturally heats up the air, increasing its temperature as per the ideal gas law:

\(PV = nRT \implies \left( \frac{P_2}{P_1} \right)_V = \left( \frac{T_2}{T_1} \right)_V\)We can feel this even when we try to blow air through our fist.

[Specific] The Blessed Lord Kṛṣṇa’s conch is named Pāñcajanya. This, as we will see below, is also a Vedic name for Agni, (the god of) fire.

[Air] The association between conches and the air is of course transparent, because we blow air through them and thus fill them with air. But this has an even deeper significance, for this wind (vāyu) is also our life-breath (prāṇa).3

[Space/Ether] In ancient Indian (meta)physics, sound is carried through ākāśa (“space/ether”). It would thus seem magical in the classical Indian system that blowing vāyu into a conch thus affects ākāśa by transmitting sound.

Names matter: The Pāṇḍavas and their conches

Back to the verses. They continue Kṛṣṇa and Arjuna’s blowing of the conches (indeed, even without a verb to go with the first half of Verse 15). They also introduce to us the other Pāṇḍavas with their conches—each one with a specific name. The fact that their conches are individually named, in contrast to Bhīṣma and to the Kaurava army, is very significant, and is a detail that we should now turn to.

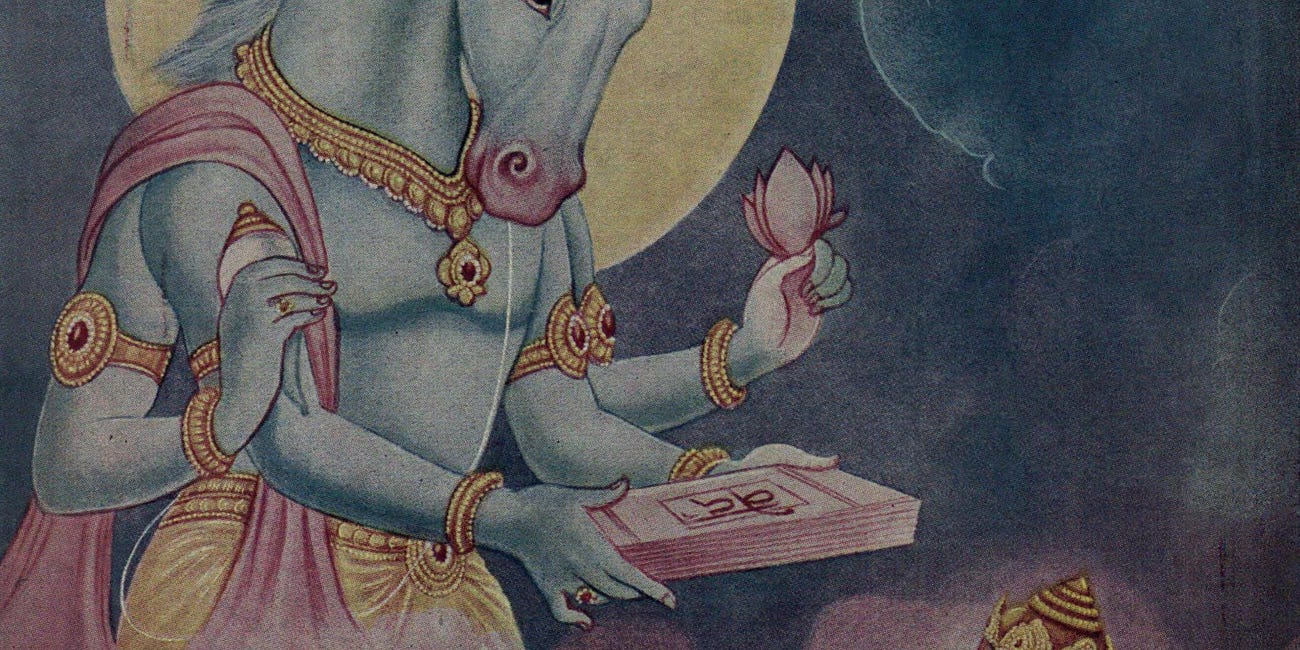

Lord Kṛṣṇa and His conch Pāñcajanya:

The classic derivation of the name Pāñcajanya for the Blessed Lord Kṛṣṇa’s conch comes from the story4 in which He kills a demon called Pañcajana under the ocean and creates the conch from the demon’s skeleton. The lesson here is that the Lord can turn what seems to us to be irredeemably evil into an instrument of good, into a tool of auspiciousness.

But there is yet another connection to the Vedas here. The first verse of the Mṛgāra verses5 uses the word pāñcajanya to describe Agni, god of fire.6 The use of this word to name both “fire” and the Lord’s conch strengthens our theory above of the five elements converging in the conch.

Arjuna and his conch Devadatta: Arjuna’s conch’s name literally means “god-given”. This compound can be understood in two different ways:

“given by a god”, i.e., it is a divine gift to Arjuna.

“given to a god”, i.e., it is a dedication by Arjuna to a deity (in this case the Blessed Lord Kṛṣṇa Himself).

But these two meanings can be reconciled if we come to realize that everything we possess is a gift from the Divine, and so everything we possess should be dedicated to serving a divine end. When we do this, then the Divine infuses, suffuses, and perfuses everything we think, speak and do. As we will see later in the Gītā, this is one of the key messages that lies at the heart of the text’s approach to spiritual awareness.

Bhīma and his conch Pauṇḍra: Bhīma gets a full half-verse to himself, with adjectives both for himself and for his conch. His is the only conch described as mahā-śaṅkha “huge conch”, as would only be fitting for someone of his reputation. And he in turn is described by two epithets, both of which are intended to convey the sheer terror that his presence would invoke in the Kaurava ranks:

Bhīma-karman, which can be regarded either as the “full” form of his name, or as an epithet “whose deeds are terrible”. Coming immediately as it does after the description of him blowing his huge conch, the implication is that no normal human could have even blown the Pauṇḍra conch. But it also indicates two further things.

First, it (in combination with his next epithet) foreshadows his fell deeds on the battlefield.

Second, it (ironically) establishes his superiority over Bhīṣma. Bhīṣma is also terrifying, but here it is not Bhīma who is intrinsically terrifying, but his deeds alone.

Vṛkôdara “wolf-bellied”. By this point, Bhīma had a well-established reputation for having a ravenous appetite (though perhaps that corvine reference in English is inadequate given the lupine adjective in Sanskrit!). But in the context of the war, this epithet foreshadows Bhīma’s hunger for devouring his enemies on the battlefield—mostly metaphorically, but most terribly, quite literally in his fulfillment of his vow to drink the blood of the Kaurava Duḥśāsana who had dared to disrobe Draupadī in a public assembly.

Yudhiṣṭhira and his conch Ananta-vijaya: Yudhiṣṭhira’s conch’s name literally means “endless victory”. There could not be a clearer foreshadowing of Yudhiṣṭhira’s victory in this war! But more than that, Yudhiṣṭhira’s victory is also an eternal one: it is the victory of dharma over adharma, of righteousness over deviousness. Yudhiṣṭhira is additionally described with two qualifiers, both of which we will look at in the next section.

Nakula and his conch Sughoṣa, and Sahadeva and his conch Maṇipuṣpaka: The twins Nakula and Sahadeva are often paired together, and this is no exception: their two conches are referred together with a single compound noun in the dual. What stands out here in the names of their conches are their beauty and their complementary aesthetic qualities.

Nakula’s conch’s name literally means “euphonious”, referring to its beautiful auditory quality.

Sahadeva’s conch’s name literally means “bejeweled bracelet”, and thus emphasizes its visual beauty.

While this is not meant to downplay Nakula and Sahadeva’s valor on the battlefield, it also serves as a reminder that there is a role for beauty in this world, even in times of war, not to mention beyond it. The fact that we see this emphasis on beauty in quick succession with the Pāṇḍava side (first with the introduction of Kṛṣṇa and Arjuna and now with Nakula and Sahadeva) but not at all on the Kaurava side tells us something about the moral natures of the two sides.

True kingship: Yudhiṣṭhira versus Duryodhana

Turning back to Yudhiṣṭhira, we see that he is qualified by two epithets, both of which are very significant choices by Sañjaya:

The first adjective is rājā “king”. As the eldest Pāṇḍava brother and the eldest of all the Pāṇḍavas and Kauravas together (Karṇa’s sad story excepted), Yudhiṣṭhira has the strongest claim to the kingship of the Kurus. But it is also precisely this kingship that Duryodhana disputes! It is thus quite telling that Sañjaya should call Yudhiṣṭhira “king” outright.

The second adjective is Kuntī-putra “son of Kuntī”. This is Sañjaya being scrupulously honest, for while Yudhiṣṭhira is indeed Kuntī’s son, he is not in fact the biological son of Pāṇḍu. Indeed, none of the Pāṇḍavas are actually pāṇḍava (“son of Pāṇḍu”), at least biologically speaking. Due to Pāṇḍu’s impotence, Kuntī had exercised a boon to conceive Yudhiṣṭhira with the deity Yama Dharmarāja.7

Varying traditions, common truth

There is a further conundrum here that emerges from looking at different text-traditions of the Bhagavad-Gītā. As we have already seen, verse I.2 is different in different traditions: Some use the word rājā (which would describe Duryodhana as “king”) while others have rājan (which would then be Sañjaya addressing Dhṛtarāṣṭra as “king!”, appropriately). However, I have not been able to find any such variation in this verse (verse I.16): Everything I have seen points to the unambiguous use of the word rājā as as adjective for Yudhiṣṭhira.

Thus, to summarize: There is some doubt as to whether Sañjaya describes Duryodhana as rājā in Verse I.2, but none whatsoever that Sañjaya describes Yudhiṣṭhira as rājā in this opening section of the Gītā. This suggests that the word rājan means something different when used to describe Duryodhana and when used to describe Yudhiṣṭhira:

[kingship de facto] Duryodhana is rājan by force of might: he is the one who sits on the throne, and is fighting for his pride and power.

[kingship de re] But Yudhiṣṭhira is rājan in the moral sense of the word: he possesses the virtues and moral standing that are the true mark of the chief of the Kurus. It is Yudhiṣṭhira who deserves to be rājan. The epithet Kuntī-putra doubles down on this: even if it is true that Yudhiṣṭhira has no Kuru blood stricto sensu, he still deserves to be king of the Kurus due to his character (and due to his divine descent).

Since this is a battle for dharma (as the very first verse of the text makes clear), it is Yudhiṣṭhira who will eventually prevail. Given that Sañjaya is praised for his clearheadedness and his dhārmika character, it should come as no surprise that he should regard Yudhiṣṭhira’s claims as just. Sañjaya, for all his employment as Dhṛtarāṣṭra’s trusted charioteer, is thus a supporter of Yudhiṣṭhira’s claim to kingship.

|| Sarvaṃ Śrī-Kṛṣṇârpaṇam astu ||

As per Puruṣottama’s Ekākṣara-kośa, the word śam (in the neuter) has three different meanings and three more in the masculine:

śaṃ sukhaṃ, śaṅkaraḥ, śreyaḥ; śaś ca sīmni nigadyate | śayane śaḥ samākhyāto, hiṃsāyāṃ śo nigadyate || (33)

śam (neuter) means happiness (I), Śiva the delighter (II), and the highest good (III). śa (masculine) is said to be a border (I), a bed (II), or violence (III).

According to Vararuci’s Ekâkṣara-nāma-mālā, the stem kha in its masculine and neuter forms has at least ten distinct meanings, expressed across five half-verses:

kham indriyaṃ samākhyātaṃ; kham ākāśam udāhṛtam || (8cd) svarge ’pi ca khaṃ samproktam; śūnye, khaḍge ’pi khaṃ smṛtam | khago ’pi khaḥ samākhyātaḥ; svarge ’pi kha udāhṛtaḥ || (9) sūrye ’pi khaḥ samākhyātaḥ; śūnyâ-’rdhe kham api smṛtam | bindau, sukhe, śrotasi khaṃ kathitaṃ pūrva-sūribhiḥ || (10)

kham (neuter) means a sense organ (I), space (II), heaven (III), a void (IV), a sword (V). kha (masculine) means a bird (I) or heaven (III) or the sun (VI). kham (neuter) can also mean an empty half (VII), a drop (VIII), happiness (IX), or the auditory canal (X).

As Owen Barfield points out in his book Poetic Diction, the concepts of “wind”, “breath”, and “spirit” are all unified in a number of ancient cultures (contra Max Müller):

We must … imagine a time when [Latin] ‘spiritus’ or [Greek] ‘pneuma’, or older words from which these had descended, meant neither breath, nor wind, nor spirit, nor yet all three of these things, but when they simply had their own old peculiar meaning, which has since, in the course of the evolution of consciousness, crystallized into the three meeanings specified—and no doubt into others also, for which separate words had already been found by Greek and Roman times.

(Poetic Diction, Ch. 4 “Meaning and Myth”, p. 81)

Narrated in the Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam, Canto X, Ch. 45: https://vedabase.io/en/library/sb/10/45/

These verses occur (in different sequences) in both the Atharva-veda [AVS IV.23] and in the Taittirīya Saṃhitā of the Kṛṣṇa Yajur-veda [KYV TaittS IV.7.15]. In both hymns the verse to Agni is the first in the sequence, though the order subsequently diverges. The version that I am familiar with is the one from the Kṛṣṇa Yajur-Veda as it is recited as part of the Svasti-vācanam:

Agnér manve prathamásya prácetaso; yáṃ Pāñcajanyaṃ bahávaḥ samindháte | víśvasyāṃ viśí praviviśivāṃsam īmahe: sá no muñcatv áṃhasaḥ ||

I am no expert in Vedic Sanskrit, which has its own subtle nuances, but a rough attempt at translation could read as follows:

I bring to mind [the deeds?] of Agni the first, the forethinker;

Him do we invoke

who, belonging to the pañcajana, is kindled by many

entering into every human habitation:May he liberate us from our afflictions!

There could be multiple reasons for the name pāñcajanya being used for Agni in this verse.

One interpretation that the pañcajana “five peoples” here are a reference to the five major lineages of kings that appear in the Vedas, all of whom followed the fire-centric Vedic religion: the descendants of Anu, Druhyu, Yadu, Turvasu, and Pūru.

Another interpretation is that it refers to the “five classes of beings” who are all involved in the Vedic sacrifices: gods, sages, ancestors, humans, and animals.

Similarly Bhīma is the son of Vāyu the wind-god and hence a half-brother of Hanumān, while Arjuna is the son of Indra, and the twins Nakula and Sahadeva are the sons of the divine Aśvin twins, conceived by Kuntī’s co-wife Mādrī.

You don’t know how eagerly awaited your posts are.