Ch. 1, Verses 2–3: Sañjaya depicts Duryodhana’s nervousness

The start of Duryodhana’s anti-Gītā

Last pakṣa, we saw the first verse of the Śrīmad-Bhagavad-Gītā, which opens with the curiosity of Dhṛtarāṣṭra.

Today, we’ll look at the next two verses, which set up an important speech by the primary antagonist of the Mahābhārata epic, Duryodhana.

Duryodhana’s speech as the anti-Gītā

Starting with verse I.3, Duryodhana delivers an 8-verse-long speech to his teacher Droṇa, followed by another verse where he addresses the generals of the Kaurava army. We will look at the details of his speech in later posts, but even in his opening verse itself (which we will cover today!), we will see the main contours of Duryodhana’s thinking: small-minded binary thinking, zero-sum bias, disrespect towards one’s teachers, an attitude of fear and paranoia, wild emotional swings, one-sided communication with no attempt to listen to others, and an inability to see the bigger picture.

As we dive into the two verses for today, I want to suggest that we should regard Duryodhana’s speech as the anti-Gītā: it is the opposite of what we should be aspiring towards. And yet, it is contained within the Gītā itself, and indeed located at its very beginning! This seems quite paradoxical at first, but just like the decision to begin the text with Dhṛtarāṣṭra, this order is meaningful: It is precisely because Duryodhana’s behaviors are not new to us. Most of us have acted in some, if not all, of these ways on multiple occasions, and may not even have been aware that we were doing so. By portraying Duryodhana—such a disliked character!—as acting in this fashion, the Gītā is getting us to reflect on our harmful attitudes and behaviors, which we should seek to dissolve and overcome as we strive to better ourselves.

The second verse: Sañjaya speaks

Sañjaya uvāca:

dṛṣṭvā tu Pāṇḍavâ-anīkaṃ vyūḍham, Duryodhanas tadā |

ācāryam upasaṅgamya rājā vacanam abravīt || (BhG I.2)In the first verse of the Gītā, Dhṛtarāṣṭra asks Sañjaya to tell him what was happening on the battlefield of Kurukṣetra. Sañjaya responds in this verse, addressing his king and focusing on his son Duryodhana:

But upon seeing the Pāṇḍava army arrayed in battle-formation, King Duryodhana approached Droṇa his teacher and spoke the following words.

Fathers and Sons

Sañjaya does not begin, as we might expect, with a description of the battlefield or of the two armies. This is partly because the Gītā is embedded within the Mahābhārata; by this point, we already know where we are, and why. But this does not explain Sañjaya’s specific choice: Why does he begin with Dhṛtarāṣṭra’s son, Duryodhana?

As any good marketer will tell you, you should listen to the Voice of your Customer! Being Dhṛtarāṣṭra’s charioteer, Sañjaya is intimately familiar with his king’s mental makeup and disposition. He knows of Dhṛtarāṣṭra’s blind love for his son, and knows that Dhṛtarāṣṭra is primarily interested in knowing his son’s state. If Sañjaya were to start anywhere else or with anybody else, he would lose Dhṛtarāṣṭra’s interest entirely.

Beginningless and endless

Sañjaya’s narration begins in medias res. (I reflect this by starting my translation with “But”, for it captures some of this feeling that is present in the original.) This is a much-praised strategy in books and movies, because it throws us right into the middle of the action. But it’s also a powerful symbolic move: in real life, unlike the movies, there is no narrative; we are always already in the middle of the action. Even if we think of birth as the beginning of life and death as its end (a view that the Gītā regards as mistaken), this is still happening within the stream of Life as a whole. We are actors in a drama that started well before we began our dialogues and that will continue even after we exit stage left.

Inputs and outputs

By the time Sañjaya starts speaking, Duryodhana has already inspected the Pāṇḍava forces and—importantly—this has already affected him. The particle tu (which I translate with “But”, only capturing a small part of its flavor) indicates a shift of topic, a contrast of emphasis. It is thus a hint that something changed in Duryodhana after he saw the Pāṇḍava army ready for war. We are not told what this change is explicitly; we must infer it from his actions and his words.

Another hint that this was not something Duryodhana had initially expected comes from the end of the first line: we are told that it is only tadā “at that point” that he does what the second half-verse describes. His actions are thus impulsive and unplanned.

What this does is to highlight Duryodhana’s unreflective behavior. He does not pause to reflect on his discomfort; the moment he sees the Pāṇḍava forces, he gets perturbed and immediately acts impulsively and unthinkingly. Duryodhana is like an undamped pendulum that, when hit by a single impulse, keeps swinging back and forth past its equilibrium point, never coming to rest.

The implication for us, recalling the idea that Duryodhana represents an anti-model, is to introduce damping—via self-reflection and other methods—into the dynamic system of our minds. We will keep returning to this topic, for the cultivation of serenity and inner peace while remaining active is one of the key topics of the Gītā.

How (not) to talk to your teacher

Let us return to Duryodhana; what does he do when perturbed? He goes up close (upasaṅgamya) to his teacher, Droṇa, and delivers a speech (vacanam) to him. The verb is suggestive of Duryodhana wanting to discuss the situation in private with his teacher.1 Combining this with our previous insight, we see that Duryodhana turns to his teacher only after being confronted with the Pāṇḍavas fully prepared for war.

What is Duryodhana seeking here from his teacher: blessings, advice, or solace? As we go through his speech over the next nine verses, we will gradually realize: Duryodhana is nervous, perhaps even afraid, that this war is not going to end well for him. And—most intriguingly—his teacher Droṇa does not reply to him.

King of the jungle

(Feel free to skip this section in your first read-through; its real import will only emerge when we contrast this verse with Verse I.16 down the road.)

Ch. 1, Verses 15–16: The battle of the conches, part 3

On this holy day of Ratha Saptamī, I seek to restart my postings of verses and commentaries from the Śrīmad -Bhagavad-Gītā. I began my sequence of posts on the same day a few years ago, so I think it is quite appropriate to re-commence on this day of all days.

Notice, finally, Sañjaya’s use of the word rājā “king” to describe Duryodhana. This one word is in fact the root of the problem: The whole reason the Mahābhārata war is being waged is to decide who should be king! Sañjaya calling Duryodhana “king” seems to be pre-judging the matter at hand.

Now, Duryodhana and his father Dhṛtarāṣṭra both believe that it is Duryodhana who should be king. Furthermore, at this point in the story, Duryodhana is the de facto king; he sits on the throne and rules the land. And finally, Sañjaya is after all Dhṛtarāṣṭra’s charioteer! For all these reasons, it makes sense if Sañjaya calls Duryodhana rājā at this point.

Interestingly, though, there are some recitation traditions of the Gītā in which the word here is in fact rājan! “O king!”. This would address Dhṛtarāṣṭra directly and not say anything about Duryodhana. This no doubt reflects the unease that people have felt with calling Duryodhana “king”.

The third verse: Duryodhana lashes out

paśyaîtāṃ Pāṇḍu-putrāṇām ācārya! mahatīṃ camūm | vyūḍhāṃ Drupada-putreṇa tava śiṣyeṇa dhīmatā || (BhG I.3)

Duryodhana begins his 9-verse-long speech to his teacher Droṇa with a seemingly innocuous verse:

Look at this grand army, o teacher[,] of the sons of Pāṇḍu, arrayed in battle-formation by Drupada’s son, your own brilliant student.

I have intentionally worded the English translation somewhat awkwardly, in order to capture a key ambiguity in the original Sanskrit. For this verse is not meant to merely inform Droṇa about the Pāṇḍava army; rather, I read it as simply dripping with Duryodhana’s barely-concealed fear, anger, and contempt towards Droṇa.

An insult hidden in plain sight?

The ambiguity has to do with how the word Pāṇḍu-putrāṇām “of the sons of Pāṇḍu” fits with the rest of the verse.

The innocuous way to read it is to connect this phrase with etāṃ … mahatīṃ camūm “this grand army”. This would follow from the previous verse, where we have already seen the word Pāṇḍavâ-anīkaṃ “Pāṇḍava army” used. In this reading, the word ācārya “o teacher!” floats freely. Put together, we get the innocuous translation:

Look at this grand army of the sons of Pāṇḍu, o teacher!However, there is also a disrespectful reading of this verse. Note the exact order of words: Pāṇḍu-putrāṇām ācārya. In Sanskrit, this is the default way to express the idea “o teacher of the sons of Pāṇḍu!” Thus, the disrespectful version would read in full:

Look at this grand army, o teacher of the sons of Pāṇḍu!

I think the ambiguity here is intentional. Duryodhana is underlining the fact that Droṇa had in fact been the teacher of the Pāṇḍavas, and is subtly blaming him for their battlefield prowess. He chooses to ignore the fact that Droṇa was equally the teacher of the Kauravas as well, and has indeed chosen to fight alongside Duryodhana in the war.

We thus see one of the key ways in which Duryodhana responds to adversity: by lashing out, by blaming others whether they were responsible or not, and by externalizing the issue so as to avoid any need for self-reflection. I need hardly note that this is not a good model to follow; all I will say is that this sets up a good contrast for Arjuna’s behavior later in this same chapter of the Gītā, which provides us with yet another anti-model, but this time one that internalizes issues beyond their legitimate extent.

Life as a zero-sum game

If the first half-verse is ambiguous, the second half is transparently insulting as Duryodhana piles on more and more blame onto Droṇa. While noting that the commander of the Pāṇḍava armies is Dhṛṣṭadyumna, Duryodhana does not actually call him out by name. Instead, he uses three separate adjectives, each of which is designed to rile up Droṇa in one way or the other.2

Duryodhana begins by calling him Drupada-putra “son of Drupada” in order to emphasize the long-standing feud between Droṇa and Drupada father of Dhṛṣṭadyumna. This is Duryodhana’s way of complaining that Droṇa has made things harder for the Kauravas by cultivating an enmity with such a powerful king.

Duryodhana then rubs salt into the wound by calling Dhṛṣṭadyumna tava śiṣya “your student”: he turns Droṇa’s fair-mindedness against him.

(The backstory here is that Droṇa had accepted Dhṛṣṭadyumna as his student and trained him sincerely, despite knowing that Drupada had begotten Dhṛṣṭadyumna with the explicit purpose of killing Droṇa.)Indeed, Dhṛṣṭadyumna is no ordinary pupil; as Duryodhana himself says, he is dhīmat “brilliant”, even “visionary”. And now all of this has resulted in strengthening the Pāṇḍava army to the point that they pose a serious threat to Duryodhana’s ambitions.

To Duryodhana, Droṇa’s generosity is nothing more than a foolish concession to an enemy. Seeing the world as “Us” and “Them”, he exhibits classic zero-sum thinking. For Duryodhana, everything is measured by how it either helps or hurts him in his conflict with the Pāṇḍavas. You’re either with him, or against him.

Echoes from the past

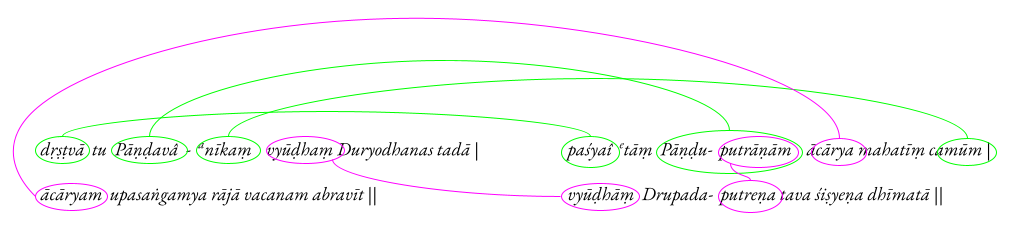

To wrap up, let us enjoy the echoes of Verse I.2 in Verse I.3. These include not just actual repetitions of words (known as “concatenation”, or śṛṅkhalika in Sanskrit), but also synonyms. In the diagram below, I’ve colored the former pink and the latter green:

The two verses start with dṛṣṭvā and paśya respective, both of which are related to the idea of seeing.3

Next, Verse I.2 has Pāṇḍava where Verse I.3 has Pāṇdu-putra. Both mean “the sons of Pāṇḍu”.

Both verses have a word for “army”: anika and camū, respectively.

Both verses contain the adjective vyūḍha “arrayed in battle-formation”, agreeing with their respective words for “army”.

Finally, both verses repeat the word ācārya “teacher, guide”.

These echoes pull our minds towards both the looming presence of the Pāṇḍava army—not just on the battlefield, but also in Duryodhana’s mind—as well as the ācārya, the exemplary teacher whose conduct is to be emulated. (And yet Droṇa is not even named at all in this whole section of the Gītā!)

Finally, these echoes also serve to contrast Sañjaya’s neutral observation of the situation with Duryodhana’s knee-jerk, emotional reaction, and his attempt to force his view of the world upon others. It is remarkable how identical sensory inputs can trigger such different responses in different people! The challenge before us, should we choose to accept it, is to be deliberative in identifying and restraining our unreflective responses; to be more serene even as we charge headlong into the open-ended adventure that is life.

|| Sarvaṃ Śrī-Kṛṣṇârpaṇam astu ||

Compare this to words like upāsanā, which is used in the sense of “worship”, but which literally means “sitting near”. Similarly upasthāna is often used to mean “worship” but literally means “standing near, waiting near”. And of course the most famous example of this sort: upaniṣad. This word is interpreted in very different ways, but one plausible etymological analysis is “sitting down nearby”, potentially because the teachings of the Upaniṣads were secrets that would only be revealed by a teacher to one student at a time, whispered, in close proximity.

Incidentally, there is a variant reading of Verse 1.3cd: vyūḍhāṃ Drupada-putreṇa Dhṛṣṭadyumnena dhīmatā. Here Dhṛṣṭadyumna is explicitly called out by name.

In fact, paśya is the suppletive imperative of the root dṛś, from which dṛṣṭvā is also derived (as per Pāṇini’s Aṣṭâdhyāyī 7.3.78). So this could technically also count as an example of a direct repetition of a word. A parallel in English would be the relationship between the words “is”, “are”, “were”, and “been”.

While these particular verses are “anti-Gita”, I love your derivation that one should constantly aspire for “cultivation of serenity and inner peace while remaining active” - but hardest to realize while in midst our own actions.

Drona being characterized as “teacher to Pandavas alone”, or the slant to rile up Drona as “son of Drupada” and such nuggets are delightful extracts.

Very interesting that you brought out that there is no narrative in real life, just opportunity for action, but I think we all secretly dream that we each have our own Sanjaya, providing narrative for eternity!

Very well articulated of a very difficult discourse