Ch. 1, Verse 14: The battle of the conches, part 2

Kṛṣṇa and Arjuna’s first appearance in the Gītā

After a far-too-long hiatus, let us continue our journey through the verses of the Śrīmad-Bhagavad-Gītā.

Catching up

Previously, we saw Bhīṣma’s blowing of his conch, followed by the noisemaking of the vast Kaurava war machine (verses I.12 and I.13).

The Kaurava challenge cannot go unanswered, of course—the next 5 verses are dedicated to the Pāṇḍavas’ response. But the nature of the Pāṇḍava response must be closely studied: They don’t break under the Kauravas’ noisemaking, nor do they respond in a robotic unison. Their response is more stately, more staggered, and ultimately more staggering to the Kauravas.

The Pāṇḍava response, part 1: Kṛṣṇa and Arjuna

I want to focus for now on just the first verse of the Pāṇḍava response, I.14. This is a hugely significant verse in the text because it marks the entry upon the scene of the Blessed Lord Kṛṣṇa alongside His friend, protagonist, and stand-in for the reader Arjuna. As we will soon see, every word of this verse carries layers upon layers of meaning that set the stage for the upcoming conversation in the Gītā between Arjuna and Kṛṣṇa.

tataḥ śvetair hayair yukte mahati syandane sthitau | Mādhavaḥ Pāṇḍavaś caiva divyau śaṅkhau pradadhmatuḥ || (BhG I.14)

It was then that Mādhava Kṛṣṇa and Arjuna the Pāṇḍava—standing in their great chariot, with splendid white horses yoked—both blew their divine conches.

A layer-cake of meanings

Let us explore the multilayered meaning of this verse, starting with the first word tatas. I’m going to explore 4 layers of meaning for this word, and for the sake of convenience will outline them here first. (This is meant to serve more as a roadmap as you read the following meanings, and not as an argument for this particular method of reading.)

Layer 1: This will be the simple, “obvious”, interpretation of the verse, read straightforwardly.

Layer 2: The plain meaning must sometimes be modified when read in the context of the surrounding verses, or the text as a whole. Additionally, there are sometimes some further suggested meanings, or at the very least “resonances” (dhvani), that come to mind.

Layer 3: The process of digging through Layer 2 can sometimes leave us with a plethora of interpretations, sometimes reinforcing one another, sometimes contradicting one another. Thus, some level of reconciliation (samanvaya) is necessary at this point to get to a deeper meaning that is, as I call it below, robust to interpretive perturbation.

Layer 4: If we continue to dig deeper, we may sometimes come upon a level of meaning that rings true at the theological or metaphysical level. This may be far removed from the previous layers, and may take a fair level of grammatical analysis to arrive at. But when we do, this layer of meaning can truly alter our picture of the verse, and potentially of reality itself.

Digging through these four layers for every single word or phrase in this verse will get exhausting, so I will do so explicitly only for this first word tatas. Elsewhere, I will limit myself to merely touching upon other possibilities.

Layer 1: “Just the facts, ma‘am” — plain, literal interpretation

The dictionary meaning of the word tatas is “then, thereupon, subsequently”. At the plainest level of storytelling, this is a straightforward indicator of a temporal sequence (krama):

First, Bhīṣma blew his conch.

Then (tatas) the Kaurava army created a ruckus.

And then (tatas again) Kṛṣṇa and Arjuna responded.

Now this in itself is significant: it makes it abundantly clear that the Pāṇḍavas’ response is in fact a response: they did not want this war but were forced into it by Kaurava behavior.

Layer 2: A chain of causes

As seen with the dictionary meaning above, tatas can also signify a causal sequence, not just a temporal one. Put differently: a phrase “A tatas B tatas C” can be understood both as “A, then B, then C” as well as “A, therefore B, therefore C”.

With this causal understanding in mind, we are pulled to recognize the Pāṇḍava response to the battle of the conches as the inevitable unfolding of Duryodhana’s craving for kingship. Duryodhana’s lust is the cause, and the inescapable effect is the Mahābhārata carnage.

Layer 3: Robustness to interpretive perturbation

“Now wait a minute,” you might object. “The Pāṇḍavas may have been sucked into the Mahābhārata war by Duryodhana, yes, but it’s not Duryodhana blowing the conch here, but Bhīṣma.” Fair enough! Let’s look at the two interpretations of Bhīṣma’s actions from I.12:

On the negative interpretation (according to which Bhīṣma is a Kaurava partisan), Bhīṣma is clearly an ancillary cause for Duryodhana’s intransigence. Had he exercised greater authority earlier as the eldest of the Kurus (Kuru-vṛddha) and reined in Duryodhana and his father Dhṛtarāṣṭra, it’s possible the war could have been averted. The use of tatas here following Bhīṣma’s action is a way of holding him responsible for the war, even if only indirectly.

On the positive interpretation (according to which Bhīṣma is invoking the Blessed Lord Kṛṣṇa by blowing his conch), the causal interpretation still holds: Call for the Supreme Lord, and He will come.

Take it even further: even if you don’t call for the Supreme Lord intentionally, but do so accidentally, He will still come! As the story of Ajāmila in the Bhāgavata-Purāṇa is meant to illustrate,1 it’s actually ultimately irrelevant whether Bhīṣma intended to invoke the Supreme Lord—the fact is that his blowing the conch invoked Him, and so He responded.

This should remind us the fact that spiritual transformation is a process, with certain specific stages, which are dependent upon being performed in a certain sequence. One of those key elements is the need to invoke (āvāhana) the Divine into all our thoughts, words, and deeds.

This understanding of tatas is thus robust to interpretive perturbations, which should give us greater confidence in its validity.

Level 4: The source of all things

But we are not done with this one word yet! Grammatically, the word tatas is identical to the pronoun tasmād, which is the pañcamī “ablative” form of the pronoun tad. We have already seen in our analysis of verse I.12 that the word tad is in fact a name for the Supreme Lord Mahā-Viṣṇu or Śrīman-Nārāyaṇa.2 At a deep level, then, the word tatas should be understood as an encoding of Nārāyaṇād “from / due to Nārāyaṇa”.

This then brings to mind the first khaṇḍa of the Nārāyaṇôpaniṣad, which describes the unfolding of all of creation from Nārāyaṇa through the near-hypnotic repetition of the word Nārāyaṇād.3

At this bedrock layer of meaning, the message of this word is that everything emerges from the Supreme Divinity who is all-pervading and who is the inner controller (antaryāmin) of all beings. We may assign causal relations to different parts, but ultimately everything comes from the Divine and ultimately everything comes back to rest in the Divine.

And all of this from the single word tatas!

Horses and chariots

The verse then follows with a description of Kṛṣṇa and Arjuna’s “great war-chariot, with splendid white war-horses yoked” (śvetair hayair yukte mahati syandane). This is the first elaborate description we have seen in the Gītā so far, and though it is exceedingly short by Sanskrit standards, it nevertheless serves two purposes:

It heightens the sense of suspense that follows the opening tatas: who is going to respond from the Pāṇḍava side to Bhīṣma’s challenge, and how? This expectancy, known as ākāṅkṣā in Sanskrit semantics, draws our attention and focus to the verse at a critical moment.

It evokes a vision of grandeur and valor that suggest (vyañjanā) both the greatness of Kṛṣṇa and Arjuna in past battles as well as their impending victory in the Mahābhārata war.

But there are also a lot of hidden meanings within this verse, as well as some deep connections with the Vedas. Let us now turn to a few of them.

White horses

The color white and the horse as an animal are both deeply significant in Hindu symbolism right from Vedic times:

Since we have already talked about Sāṅkhya, let us note that white (śveta) is the color associated with the sattva thread (guṇa) that makes up reality. Sattva is in turn associated with lightness, illumination, and the good.

Horses, for their part, are connected with intelligence while their neigh, in a ritual context, is associated with the recitation of the Vedas themselves. Since there are at least three horses referred to here (hayaiḥ), we might assume that each Veda gets one horse.

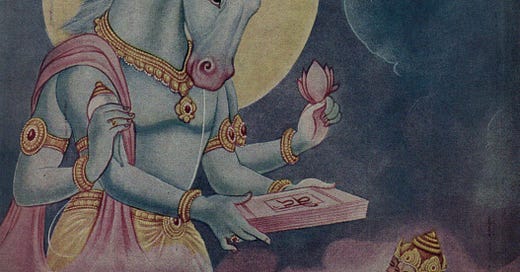

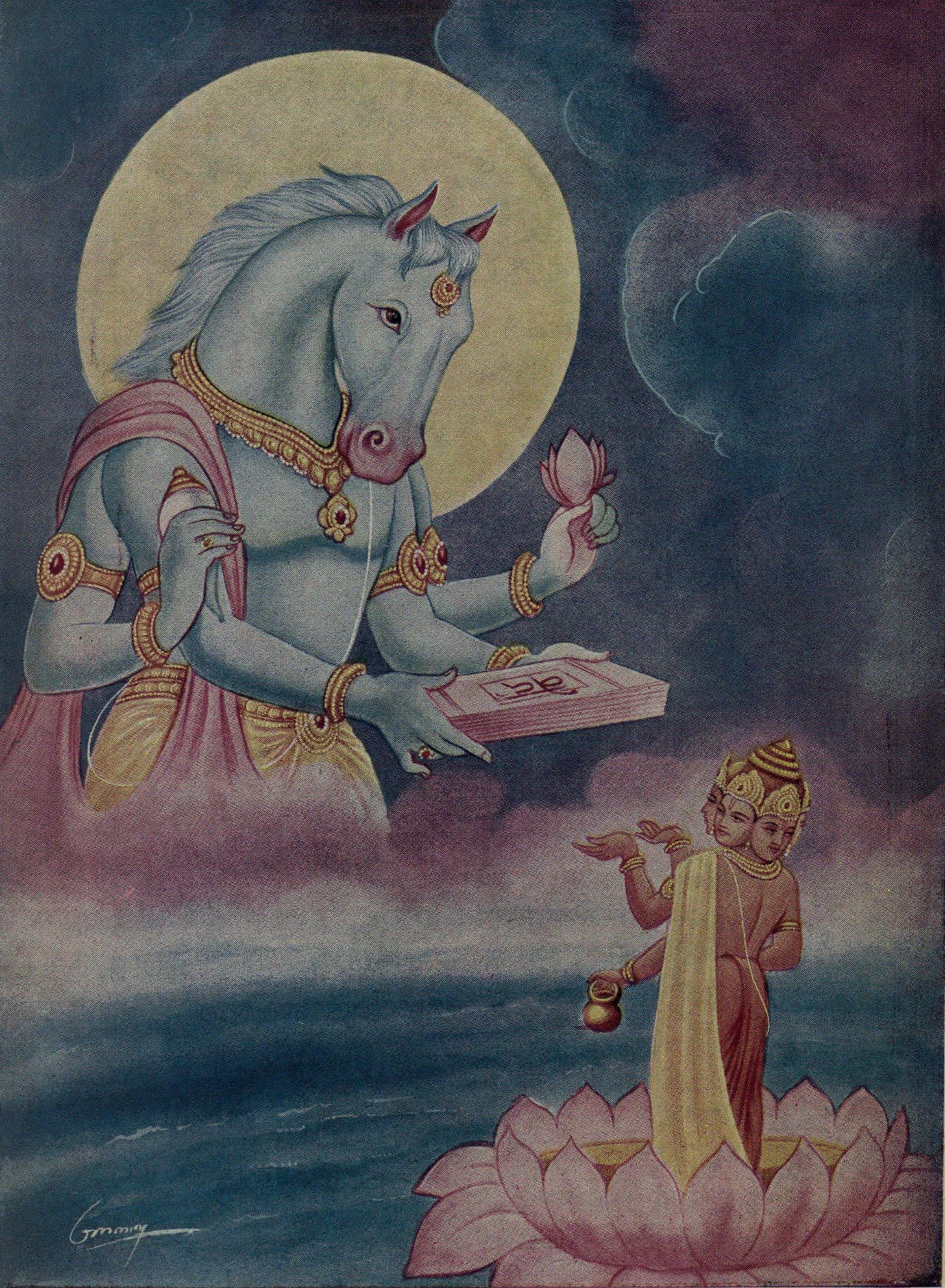

A hint of the Divine

For Śrīvaiṣṇavas in particular, the combination of the color white and the horse is especially significant as it brings to mind Lord Hayagrīva, the hippocephalic form of Śrīman-Nārāyaṇa who is regarded as the fons et origo of all knowledge and the custodian of the Vedas in particular.

The yoke

Note, finally, that these white horses are yoked (yukta) to the chariot. This is after all the original meaning of the root yuj, so it is not unsurprising. What is more interesting is the fact that this root is also the source of the word yoga, which is of course absolutely central to the Śrīmad-Bhagavad-Gītā itself (to the point where each chapter of the Gītā is sometimes called a yoga). We will continue this line of thinking once we come up with an appropriate understanding of the chariot as well—to which we now turn.

The chariot as a metaphor

Millennia ago, chariots formed the terrifying vanguard of Bronze Age and Iron Age armies lucky enough to have access to horses. No wonder that the chariot plays such an important role in not just the Mahābhārata but also in Vedic hymns.4 But the chariot is important here not just because it is cutting-edge military technology, but because the horse-chariot-charioteer-warrior complex is an incredibly common symbol and metaphor for the human mental-emotional-consciousness complex.5 While the exact correspondences can vary by the telling, here is one interpretation:

The horses stand for our animal instincts, our primal drives, our sense-driven impulses (indriyas). They are essential for driving the chariot forward, but if they are not controlled, the whole setup will run wild.

The warrior is our ego (ahaṅkāra), the self-important, self-centered ruler who wants to get his way.

The charioteer is the superego, the real controller of the reins (antaryāmin), who understands what the warrior wants and who usually grants it, but who is otherwise detached from the conflict itself.

The chariot itself is then the mental organ (manas, often mistranslated as “mind”), which connects our sensory inputs, our ego, and the higher self.

The specific word used for “chariot” in this verse is syandana, which itself reinforces this identification of the chariot with the mental organ. While the word itself is understood to mean “chariot”, it is in fact derived from the root syand “to flow, to trickle”. A syandana is literally “a flowing”, which may have referred to the rolling motion of a chariot along the ground in contrast to the running of humans and horses. But in the context of this verse, what come to mind are two other things that are commonly identified with flowing streams in Hindu philosophy:

the speech-stream (sometimes called vāk-pravāha)

the mind/consciousness-stream (citta-santāna especially in Buddhist contexts).

Like a small rivulet running over rocky ground, or a chariot without shock absorbers being pulled by wild, wayward horses, the unsteady mind is jumpy and jittery from moment to moment.

A grammatical interlude: The interpretive potential of homophony within Sanskrit nominal paradigms

The word sthitau (in the phrase śvetair hayair yukte mahati syandane sthitau) can be taken straightforwardly to be the nominative dual (prathamā dvivacana) form of the adjective sthita “stood”. It is in the dual because it describes both Kṛṣṇa and Arjuna as they stand in their chariot (syandane). The locative (saptamī) ending of the word syandana is thus used to mark it as the locus (adhikaraṇa) of this action of standing.

However, sthitau can also be understood as the locative singular (saptamī ekavacana) of the noun sthiti “condition, state” and also in a slightly extended sense “steadfastness, stability, permanence”. This extended use of the noun sthiti is philosophically very significant:

It appears in standard phrases like sṛṣṭi-sthiti-pralaya (“creation, preservation, destruction”), which correspond to the operations of the great gods Brahmā, Viṣṇu and Śiva.

Incidentally, this correspondence shows the distinctive role of Viṣṇu in preserving the sthiti of the cosmos.

It also plays a key role in Yoga, according to which the fluctuations of consciousness (citta-vṛtti) can be restrained (nirodha) by the constant practice (abhyāsa) of keeping the mind in a tranquil state (sthiti).6

With this interpretation, the locative ending of the word sthiti now describes the locus (adhikaraṇa) of the conch-blowing of Kṛṣṇa and Arjuna—but this locus is not a physical locus, but rather the psychological state of steadfast tranquility. In this case, though, the locative ending on syandane and yukte must be understood as a locative absolute (sati-saptamī) that indicates the condition under which sthiti is achieved: “in a state of tranquility, when the chariot is yoked to the horses.”

Putting everything together for the first half of this verse: only when our senses are controlled and coordinated by sacred, sāttvic speech, and when our mind+speech-stream is checked by the power of yoga—only then, in that state of tranquility, can our ego truly be receptive to the gentle murmurings of the Gītā from our inner Divinity.

Kṛṣṇa and Arjuna

And what a powerful entry that Divinity makes in the Gītā! The second half of the verse can be read as a self-contained sentence: “Mādhava and the Pāṇḍava too both blew their divine conches.” There are a number of little hints sprinkled across this half-verse indicating the superiority of Kṛṣṇa and Arjuna’s effort over the Kaurava one:

the explicit use of the word divya- “divine” to describe their conches

the addition of the pra- prefix to the verb root dhmā “to blow” which suggests greater intensity and a sort of progressive, forward motion.

But in order to keep things manageable, I will highlight three questions here, in the order in which they show up in the verse:

Why is Kṛṣṇa called “Mādhava” here?

What is the deeper symbolism of the conch here?

What is the significance of Kṛṣṇa and Arjuna acting together here?

I will answer the second question in my next post, when we look at verses I.15–16. Let us look at the other two questions now.

Q1. Why is Kṛṣṇa called “Mādhava”?

This is the first time that the Blessed Lord Kṛṣṇa is referred to in the Śrīmad-Bhagavad-Gītā directly, but He is not referred to as “Kṛṣṇa”, but rather as “Mādhava”. These are precisely the kinds of moments in reading a text like the Gītā that should compel us to stop and ponder the significance of this choice.

The first, and most straightforward, observation is that the name Mādhava- shows up in the Viṣṇu Sahasranāma in the very same verse [VS 78; see footnote 2] as the name tad- which we discussed earlier when talking about Bhīṣma, as well as (potentially) the word tatas at the beginning of verse I.14. This is of course not to be taken as “proof” that the word tasya in verse I.12 of the Gītā is in fact referring to the Blessed Lord (instead of Duryodhana), but it is certainly a curious coincidence at the very least and a sign that should prompt us to think.

Next, as we look to decipher the meaning of this name, we notice that it can be parsed in different ways:

One option is to analyze it as being derived from the word madhu “honey, mead”. (This sort of derivation of a noun from another noun is known as a taddhita in Sanskrit grammar.) Thus, mādhava would mean “honey-like”, hence “sweet”, and so “charming, attractive” and so on. Kṛṣṇa is thus being highlighted for His sweetness and his ability to delight and charm us all.

Additionally, the word madhu can also refer to the spring season (in which of course bees collect nectar from flowers to produce copious amounts of honey). In this case, mādhava can then mean “vernal”, and can highlight Kṛṣṇa’s ability to make our heart-lotuses blossom. This interpretation is thus a hint to the manner in which Kṛṣṇa will eventually restore life to Arjuna’s withered self-confidence.

Another option is to analyze the word as a compound (samāsa) of the two words mā “Lakṣmī” and dhava “husband”. Thus Mādhava is simply the “Husband of Mahālakṣmī” and thus an explicit acknowledgement that this is no mere man we are speaking about, but Śriyaḥ pati, Śrīman-Nārāyaṇa, the Supreme Lord who is eternally inseparably intertwined with His beloved Śrī Lakṣmī. As the ultimate source of all prosperity, both material and spiritual, Mahālakṣmī’s presence at the beginning of this line and of this name of the Lord indicates that success will ultimately go to the Pāṇḍavas.

Finally, we note that the name Mādhava is also closely linked with another name for Viṣṇu / Kṛṣṇa: Madhu-sūdana. Here the word Madhu refers to a demon of that name who was destroyed (sūdana) by the Lord. Thus, while this may not be an explicit meaning for the name Mādhava, we do hear an echo of the demon-destroying aspect of the Blessed Lord—again a hidden indication of the Kauravas’ impending defeat.

Q3. Why are Kṛṣṇa and Arjuna acting together here?

In a way, we have already seen the answer to this in our exploration of the chariot metaphor above: Arjuna is the ego in us (ahaṅkāra) while the Blessed Lord Kṛṣṇa is the super-ego, the inner controller (antaryāmin). The goal of spiritual transformation is to get to the point where ego and the inner controller are acting in concert—indeed, where the ego is led by the inner controller in pursuit of dharma. Indeed, Arjuna is not referred to by his given name in this verse at all, but by his patronymic Pāṇḍava “son of Pāṇḍu”, indicating that he is not operating at this point out of a sense of his ego.

From an egotistical perspective, this sort of subordination might seem like an act of surrender or of loss of independence, but from a higher perspective, this is the path that leads to spiritual growth. After all, the charioteer sits in front of the warrior: it makes sense that the charioteer should lead the way!

A flash-forward to the end

It is a masterstroke of narrative that the Gītā both begins and concludes with Kṛṣṇa and Arjuna acting in concert: verse XVIII.78, the final verse of the Gītā, famously ends with Sañjaya’s declaration:

yatra Yogêśvaraḥ Kṛṣṇo, yatra Pārtho dhanur-dharaḥ | tatra Śrīr, vijayo, bhūtir, dhruvā nītir matir mama || (BhG XVIII.78)

Where there is Kṛṣṇa the Lord of yoga, where there is Arjuna son of Pṛthā the archer—there there are śrī, victory, prosperity, and wise righteous conduct. Such is my opinion.

We once again see in this final verse the co-presence and co-operation of Kṛṣṇa and Arjuna (with Arjuna again referred to not by his given name but this time by his matronymic, indicating his biological relationship to Kṛṣṇa). Furthermore, we also notice the repetition of the notion of yoga as well as the eternal co-presence of the Lord with His eternal consort Śrī Mahālakṣmī. The key elements of verse I.14 are thus reiterated at the conclusion—but then that raises the next question: does that mean that the seven-hundred-odd verses in the middle are a waste if they don’t drive things forward at all?

Not in the least. In a way, this is the nature of true spiritual transformation, in which we rework ourselves and return to a deeper understanding of who we are. As the old saying about enlightenment in Zen goes: “In the beginning, mountains are mountains and rivers are rivers. Later, mountains are no longer mountains and rivers are no longer rivers. In the end, mountains are once again mountains and rivers are once again rivers.”

Conclusion

I fear this post may have gone on for far too long, but the significance of this verse cannot be overstated. It’s a classic example of a verse that appears to be utterly straightforward on the surface; dig a little deeper, though, and you see the myriad interconnections and the multiple meanings that are densely packed into these thirty-two syllables. In a sense, this verse is the true beginning of the Śrīmad-Bhagavad-Gītā.

|| Sarvaṃ Śrī-Kṛṣṇârpaṇam astu ||

Ajāmila was a dissolute womanizer and thief—not so different from most of us ultimately!—who, upon seeing the henchmen of Yama Dharmarāja, god of death and justice, panicked and called upon his son named Nārāyaṇa for help. This accidental invocation of the Lord’s name was enough to bring the Lord’s servants to his defense and to grant him liberation. As the Bhāgavata Purāṇa says:

sāṅketyaṃ, pārihāsyaṃ vā, stobhaṃ, helanam eva vā | Vaikuṇṭha-nāma-grahaṇam aśeṣâgha-haraṃ viduḥ || [BhP VI.2.14]

The wise know that taking the name of the Lord of Vaikuṇṭha—even if used to refer to something else, or done in a mocking manner, or chanted as mere filler syllables, or uttered even out of contempt—utterly wipes out all spiritual stains.

For convenience, the full verse reads:

eko, naîkaḥ, sa(, )vaḥ, kaḥ, kiṃ, yat, tat, padam anuttamam | loka-bandhur, loka-nātho, Mādhavo, bhakta-vatsalaḥ || (VS 78 = MBh XIII.135.91)

A simple prose translation of this khaṇḍa would read as follows:

The Supreme Person Nārāyaṇa desired “I should create progeny.”. From Nārāyaṇa arises breath; mind and all the senses; space, air, light/fire, water, and all-bearing earth. From Nārāyaṇa arises Brahmā. From Nārāyaṇa arises Rudra Śiva. From Nārāyaṇa arises Indra. From Nārāyaṇa arise the Prajāpatis. From Nārāyaṇa arise the twelve Ādityas, the [eleven] Rudras, the [eight] Vasus, and all the Vedic meters. From Nārāyaṇa alone are they are generated; in Nārāyaṇa do they all operate; in Nārāyaṇa do they all ultimately come to rest.

The famous jīmūtasyêva hymn (Ṛg Veda VI.75 as well as Kṛṣṇa Yajur Veda Taittirīya Saṃhitā IV.6.6) includes multiple verses in praise of the chariot, its horses and the charioteer. At some point in the future I will post an extended reflection on this hymn and its link with the Gītā.

This symbolic identification is so common that the word mano-ratha (literally, “mind-chariot”) has simply come to mean “desire” or “intent” in modern Hindi. The intermediate step, in which the word mano-ratha is still being used in Sanskrit as a conscious chariot metaphor for the uneven operation of the mind, can be seen in the final verse of the Sudarśanâṣṭaka by Swāmī Vedānta Deśika.

dvi-catuṣkam idaṃ prabhūta-sāraṃ paṭhatāṃ Veṅkaṭanāyaka-praṇītam | viṣame ’pi mano-rathaḥ pradhāvan na vihanyeta rathâṅga-dhurya-guptaḥ || (SA 9)

The mind-chariot of the one who, safely ensconced within the spinning wheel of Lord Sudarśana, recites these eight verses brimming with power composed by Veṅkaṭanātha will never stumble, not even on the most uneven of terrain.

This can be put together from a few different sūtras from the Yoga Sūtras of Patañjali:

yogaś citta-vṛtti-nirodhaḥ | (YS I.2) abhyāsa-vairāgyābhyāṃ tan-nirodhaḥ | (YS I.12) tatra sthitau yatno ’bhyāsaḥ | (YS I.13)