We have seen, in the last several verses, how different clusters of divinities and dignitaries all come to pray to Lord Śrīnivāsa and Padmāvatī Tāyār early in the morning. As the climax of this sequence, we will now look at two verses together, connected as they are not just by the repetition of words and roots, but also by their themes.

tvat-pāda-dhūli-bharita-sphuritô-utttamâ-aṅgāḥ svargâ-apavarga-nirapekṣa-nijâ-antaraṅgāḥ | kālpâ-āgamâ-ākalanayā ākulatāṃ labhante Śrī-Veṅkaṭâcala-pate! tava suprabhātam || (VSu 19) tvad-gopurâ-agra-śikharāṇi nirīkṣamāṇāḥ svargâ-apavarga-padavīṃ paramāṃ śrayantaḥ | martyā manuṣya-bhuvane matim āśrayante Śrī-Veṅkaṭâcala-pate! tava suprabhātam || (VSu 20) त्वत्-पाद-धूलि-भरित-स्फुरितो-ऽत्तमांगाः स्वर्गा-ऽपवर्ग-निरपेक्ष-निजा-ऽन्तरंगाः । कल्पा-ऽऽगमा-ऽऽकलनया ऽऽकुलतां लभन्ते श्रीवेङ्कटाचल-पते! तव सुप्रभातम् ॥ 19 ॥ त्वद्-गोपुरा-ऽग्र-शिखराणि निरीक्षमाणाः स्वर्गा-ऽपवर्ग-पदवीं परमां श्रयन्तः । मर्त्या मनुष्य-भुवने मतिम् आश्रयन्ते श्रीवेङ्कटाचल-पते! तव सुप्रभातम् ॥ 20 ॥

[19] Your foremost servants, whose heads shine with the dust from Your feet care not a whit either for heavenly delights or for total liberation. Instead, they fear the ending of this era for they wish to continue serving You here: O Lord of the sacred mountain wealth-weaving, sin-cleaving Venkatam, a blessed morning unto You! [20] Seeing the soaring spires of Your gateway towers, the beings who have already attained high heaven and full liberation seek to be born on earth as mortals just so they can serve You here: O Lord of the sacred mountain wealth-weaving, sin-cleaving Venkatam, a blessed morning unto You!

What does it mean to want to serve the Divine?

We have already seen hosts of divine figures congregating at the doorstep of Lord Śrīnivāsa, seeking His blessings first thing in the morning. Verse 19 turns to the closest personal servants of the Lord. It does not name them, but it says that the dust of His feet shines on their heads: a poetic way to say that they have placed His feet on their heads, they have surrendered themselves wholly to Him. We can understand these to be the great Āḻvārs and Ācāryas who performed their act of taking refuge (śaraṇāgati) at the feet of the Lord and Lady of Tirupati.

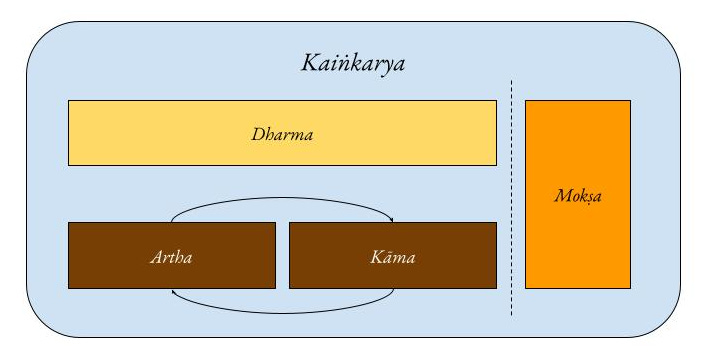

What is remarkable about them is that they desire neither heaven (svarga) with all its delights, not even liberation (apavarga) from the unending cycle of saṃsāra! What is shocking about this declaration is that, hitertho, these have been the two highest end-states of human activity (puruṣârtha).

The ends of human existence

A quick recap on what the puruṣârthas traditionally are: They represent the 3 (or 4) primary motivations for human (non-)action.

The first, kāma, covers everything we might do for sense gratification. This is predominantly the mode through which animals might interact with the world.

The second, artha, covers everything we do to acquire resources. This might involve forgoing immediate sense gratification for greater consumption in the future. The kāma–artha tradeoff is thus the classical Indian framing for what we might today call the problem of intertemporal choice (though without the mathematics).

The third, dharma, traditionally encompasses both ritual (yāga, homa) and ethical actions of giving away (dāna), in order to obtain some desired end. It is the consumption of artha to serve a desire that is not an immediate sensory kāma, but something that can stretch well into the future or even into the afterlife. The highest of these end-states is svarga, heaven, in which one can enjoy the company of the gods so long as one’s merit lasts, then to be reborn on earth.

The fourth, mokṣa, is different from the other three entirely. While the first three all involve performing actions (pravṛtti) to accomplish goals, mokṣa is about conscious withdrawal (nivṛtti) to break out of the cycle of saṃsāra entirely. The end-state this results in is called by various names like mukti, kaivalya, and apavarga, depending on one’s specific understanding of the nature of this state. Mokṣa is not a specific end to be desired for, for then this would be no different from dharma or even kāma; it is something that emerges first as a realization and then from the restraining of other desires.

But what these true devotees seek is none of the above: As with mokṣa, they do not actively desire anything for themselves, for their own sakes. As with the other three, though, they wish to continue performing actions in the world. How is this circle to be squared? By serving Lord Śrīnivāsa for His own sake in His temple form in Tirupati in our world, for as long as our world continues to exist, until the next pralaya dissolution of the cosmos.

This selfless service to the Divine Couple and to Their devotees is kaiṅkarya (or sevā), and it can (and should) encompass everything one does so long as one does it with the right intentions, the right focus, and the right dedication.

Aspiring to a human birth

The exaltedness of these devotees is then further underscored in Verse 20: You might think that this desire to stay on earth is limited to humans who haven’t already tasted the delights of heaven or of the state of ultimate liberation. Surely nobody in heaven needs to stand for hours in sweltering heat amidst jostling crowds to catch a glimpse of the Divine?

But according to Verse 20, even those human beings who have already reached heaven or liberation, who are no longer trapped in mortal bodies, actively seek to be reborn as mortals so they can serve Lord Veṅkaṭeśvara on earth! And all it takes is a glimpse of the tall gopuram gateway towers of Tirupati to kindle this desire in those who have supposedly conquered desire.

The grammar of the verse also points to the rapidity of this transformation. The verbal form nirīkṣamāṇāḥ is a present participle (or śatr-antra in Pāṇinian terminology), and thus expresses the simultaneity of seeing the gopurams of Tirupati and of desiring to be reborn as humans to serve the Lord. But of course, this is no ordinary act of seeing the towers; it is a holistic, all-encompassing view of the gopurams as cosmic entities and as spiritual doorways, inviting pilgrims to enter the temple and be transformed internally and externally.

May we all be blessed with such a beatific vision!

An inspiration from Tamil poetry

These two verses from the Śrī-Veṅkaṭeśa-Suprabhātam remind me of one of my favorite set of Tamil pāsurams: the fourth decad of Kulaśekhara Āḻvār’s Pĕrumāḷ Tirumŏḻi, beginning with the words Ūn-ēṟu śĕlvattu. This is a truly remarkable set of 11 pāsurams in which Kulaśekhara Āḻvār systematically describes his desire for reincarnation, not liberation, just so long as he can be associated with Lord Śrīnivāsa or with the sacred site of Tiruvēṅkaṭam in some form or the other.

In the first 8 pāsurams, he expresses to be reborn respectively as:

A heron living on the banks of the Swāmī Puṣkariṇī tank (Kōn-ēri vāḻum kuruku āy)

A fish in the mountain streams of Tiruvēṅkaṭam (Tiru-vēṅkaṭac cunaiyil / mīn āy)

A companion to the golden cupbearers of the Lord of Tiruvēṅkaṭam (Vēṅkaṭak kōn tān umiḻum pŏn vaṭṭil piḍitt’ uḍanē)

A champaca tree on the mountain (śĕṇbagam āy niṟkum Tiru-vuḍaiyēn āvēnē)

A thicket of grass on the mountain (stambhakam āy)

A golden mountain much like Tiruvēṅkaṭam itself (pŏṟkuḍavu ām … āvēnē)

A jungle stream gurgling and splashing upon the mountain (kān āru āyp pāyum karuttu uḍaiyēn āvēnē)

A winding trail upon the mountain leading up to the Lord (nĕṟi yāyk kiḍakkum nilai-yuḍaiyēn āvēnē)

In the famous ninth pāsuram, he then calls out to Lord Śrīnivāsa, asking for something very specific:

cĕḍi yāya val-vinaigaḷ tīrkkum Tiru-mālē! Nĕḍiyānē! Vēṅkaṭavā! nin kōyil in vāsal aḍiyārum vānavarum arambaiyarum kiḍand’ iyaṅgum paḍi yāyk kiḍand’ un pavaḷa-vāy kāṇbēnē (KPTM IV.9)

Azhwar prays to Lord Veṅkaṭeśvara who is eternally and inseparably united with His Padmāvatī:

O Lord eternally united with His Śrī who terminates our endless evil deeds proliferating like wild grass! O Lofty Lord! O Lord of Tiru-vēṅkaṭam! At that sweet, sacred door to Your temple, where devotees and the gods and the apsarases all come, prostrate themselves, and then get up and go, let me remain lying at—as!—Your doorstep for eternity, so that I may look upon Your coral-red lips forever.

To this day, the last threshold that pilgrims are allowed to approach (though not cross) in Tirupati, just outside the sanctum sanctorum, is known as the Kulasekhara Paḍi, which can mean both “Kulaśekhara’s step” as well as “the step that is Kulaśekhara”.

Finally, in the 10th pāsuram, Kulaśekhara Āḻvār asks—lest his last ask be seen as too egotistical—to be reborn as anything whatsoever on the golden mountain of his beloved Lord of Tiru-vēṅkaṭam (Tiru-vēṅkaṭam ĕnnum Ĕm-pĕrumān pŏn-malai mēl ēdēnum āvēnē).

|| Śrī-Padmāvatī-nāyikā-sameta-Śrī-Śrīnivāsa-parabrahmaṇe namaḥ ||

Share this post