Ch. 1, Verses 10–11: A profusion of confusion

Duryodhana’s speech and its significance for us

After our detour through the world of Sāṅkhya,

we return this pakṣa to Duryodhana, the last two verses of whose speech we will now wrap up. We will see how these two verses encapsulate all of Duryodhana’s worst tendencies, and then take some time to reflect on just why the Śrīmad-Bhagavad-Gītā places him at the beginning of the text.

Verse I.10: Conflicted soul, conflicted words

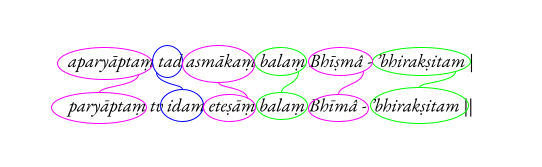

Duryodhana’s internal tensions spill out in Verse I.10, which is a deeply paradoxical and polyvalent verse. The Sanskrit text appears to be simple and full of parallel structures, but it is in fact highly ambiguous and can be interpreted in entirely opposite ways. We can literally hear the parallelism in this verse when we read it out aloud:

aparyāptaṃ tad asmākaṃ balam Bhīṣmâ-’bhirakṣitam | paryāptaṃ tv idam eteṣāṃ balaṃ Bhīmâ-’bhirakṣitam || (BhG I.10)

Given the artful construction of the verse, this ambiguity has to be intentional on the poet’s part: we are meant to be confused by it; we must recognize it as truly expressing the confusion and tumult within Duryodhana’s mind. I have tried to capture this ambivocality in translating the verse as follows:

“Therefore our force, guarded by Bhīṣma, is unlimited-yet-inadequate, whereas this force of theirs, guarded by Bhīma, is limited-yet-adequate.”

Interpretive challenges galore

There are two separate interpretive challenges in the Sanskrit original of this verse, for those who care about such details:1

The first has to do with understanding the meaning of the words aparyāptam and paryāptam in the two halves of the verse.

The second has to do with the potentially confusing use of the pronouns tad and idam.

Pronoun trouble

Let us start with the second issue, for its resolution is fairly straightforward. The challenge lies in the fact that, whereas Duryodhana is talking about his army (asmākaṃ balam) in the first half-verse, the pronoun used there is tad, which means “that one, over there”; similarly, although he is talking about the Pāṇḍavas in the second half, he uses the pronoun idam “this one, over here”. In other words, the spatial references seem to be the exact opposite of what we might expect!

One potential resolution

Now, one way to fix this potential problem is to claim that tad in the first half-verse does refer to the Pāṇḍavas and idam in the second half-verse does refer to the Kauravas, as the spatial logic would suggest.

This would yield the following translations of the half-verses:

“That force, over there, of the Pāṇḍavas, is aparyāpta compared to our force, guarded by Bhīṣma.”

“This force, over here, of ours, is paryāpta compared to their force, guarded by Bhīma.”

[I’m leaving the words paryāpta and aparyāpta untranslated for now, as we will look at them in the next section.]

My preferred resolution

However, while this interpretation is plausible (though it has its issues), there is an alternative interpretation which I personally find more convincing, and which I have therefore tried to reflect in my translation: The pronoun tad is frequently used to indicate causality, meaning “thus” or “therefore”. Interpreting it this way would not only eliminate the problems with spatial reference in the first half-verse, but would also causally link the situation described in the first half-verse with the previous verses of Duryodhana’s speech.

And while idam still indicates the proximity of the Pāṇḍava forces in the second half-verse, it is not clear why this should be a problem. After all, the two armies are gathered facing each other in fairly close proximity, such that Duryodhana can see the Pāṇḍava heroes and identify them without much trouble.

This is in fact reinforced by the use of yet another proximal pronoun eteṣām “of these people” in the same verse, not to mention Duryodhana’s use, in the very first verse of his speech, of the proximal pronoun etām “this [army]”. If anything, Duryodhana’s repeated use of the proximal pronoun highlights how up close and personal the Pāṇḍavas are, and how unnervingly in-his-face their forces seem to be to Duryodhana!

With this interpretation, the two half-verses can be understood thus:

“Therefore [given all the heroes and generals on both sides described in the last few verses], our force, guarded by Bhīṣma, is aparyāpta.”

“This force, though, of these Pāṇḍavas, guarded by Bhīma, is paryāpta.”

This is the general thrust of the translation, but clearly, we need to figure out what paryāpta and aparyāpta mean in order to actually decipher this verse!

Necessity and sufficiency

The two words paryāpta and aparyāpta are clearly opposed in meaning, as indicated by the privative prefix attached to the second word (known as naÑ in the Pāṇinian system). If we can figure out the meaning of paryāpta, then, we can start to make sense of this verse.

The trouble for us, though, is that paryāpta has two rather different meanings that apply in this context:

One meaning, the more literal one, is “surrounded”. The prefix pari- here should remind you of words like perimeter in English, and the word thus conveys the sense of being enveloped, enclosed, circumscribed, and limited. (In this case, it is synonymous with the word parimita.)

The second meaning is more idiomatic: it means “adequate” or “sufficient”, hence “capable”. (It is in this case synonymous with the word samartha.)

Corresponding to these two meanings of paryāpta are the two antonymic meanings of aparyāpta:

The first is literally “not surrounded”, which we can understand as “unlimited” or “uncircumscribed”, and hence as “free to operate”.

The second meaning is “inadequate”, “insufficient”, or even “incapable” (asamartha).

It should be clear that these two pairs of meanings are very different in polarity and hence in significance for Duryodhana! We thus end up with two very different meanings for the verse as a whole:

Taking (a)paryāpta to mean “(un)limited”, the verse indicates that the Kaurava army is far larger than the Pāṇḍava army, and can effectively surround the latter.

Taking (a)paryāpta to mean “(in)sufficient”, the verse indicates that the Kaurava army is incapable of taking on the Pāṇḍava army, even though it is bigger.

It is exceedingly difficult to come to a definitive answer as to which interpretation is the right one—and to me, that confusion is exactly what this verse is supposed to capture. Duryodhana is not thinking or speaking clearly at this point; he may not himself know what he thinks, and he certainly is not able to articulate it clearly and unambiguously to anybody.

Sonic envelopment

Let us note another artful piece of word-play here: the two half-verses end in balaṃ Bhīṣmâ-’bhirakṣitam and balaṃ Bhīmâ-’bhirakṣitam respectively.

The two quarters are virtually identical—with the one exception being the hushing retroflex sibilant ṣ in Bhīṣma’s name. Bhīṣma’s name is a proper superset2 of Bhīma’s name, even though the two names both mean the same thing: “terrifying”. This might suggest that Duryodhana expects the Kaurava army to overcome and overwhelm the Pāṇḍava army—at least so long as Bhīṣma is in charge.

Alternatively, though, we can see the ṣ (the key distinguishing feature of Bhīṣma’s name compared to Bhīma’s name) being surrounded on both sides by bhī and ma respectively. While not all Sanskrit monosyllabic words have meanings, these two syllables do have meanings, and particularly apposite ones at that:3

bhī means “fear”, as is fairly well known.

ma refers to, among other possibilities, Śiva, Lord of endings (the real Terminator, if you will!).

We might understand this poetically as suggesting the following: Fear is the anvil that holds the Kauravas in place; Śiva, in the form of the mighty Pāṇḍavas, is the hammer that brings about their doom.

Verse I.11: The protector and the protected

The next verse provides us with a further peek into Duryodhana’s state of mind, which I think does swing the balance of interpretation towards the more despairing interpretation of verse I.10. Duryodhana’s dependence on Bhīṣma and his concerns for his side emerge in the last verse of his speech. In comparison to the previous verses, this verse is refreshingly straightforward to translate. And yet even here we see Duryodhana’s fear!

ayaneṣu ca sarveṣu yathā-bhāgam avasthitāḥ | Bhīṣmam evâ ’bhirakṣantu bhavantaḥ sarva eva hi || (BhG I.11)

“Positioning yourselves along all vectors of attack, make sure all of you guard Bhīṣma for sure.”

A wider audience

The use of the plural pronoun bhavantas and of the plural imperative verb abhirakṣantu indicate a shift in Duryodhana’s addressees: He is no longer speaking secretly to Droṇa, but is instead addressing all his generals directly.

Building on his previously expressed reliance on Bhīṣma in holding the Kaurava forces together, Duryodhana lays out his strategy for his generals: it is essential for the Kauravas to ensure Bhīṣma’s continued survival. Duryodhana thus orders his generals to reorganize their battle formation to guard Bhīṣma from all directions.

A defensive mindset

Duryodhana enjoys a large numerical advantage over the Pāṇḍavas and has potentially the greatest fighters of the age on his side—and yet his mindset is entirely defensive! He wants his generals to focus on protecting Bhīṣma the grandsire—the very person who is protecting the Kaurava army as per his previous verse! The concatenation of words derived from the root abhi+rakṣ in verses I.10 and I.11 is particularly telling, as is the inversion of Bhīṣma’s role in the two verses: In I.10, he is the agent of protection (kartṛ), but in I.11 he is now the object of protection (karman).

Similarly repetitive is Duryodhana’s use of the emphatic particle eva in the second half-verse: it is Bhīṣma who is to be protected, and it is all of the other leaders, including Droṇa, who must protect him. (I’ve tried to play up the awkwardness of this repetition by also repeating the word “sure” in my rendition.) Again notice the implicit disrespect to, or at least the subordination of, Droṇa: it is as if he thinks Droṇa must atone for the “sin” of favoring the Pāṇḍavas earlier in his life by now protecting Bhīṣma at all costs.

It is this insistence and defensive mindset that leads me to think that we should not overemphasize the self-confident interpretation of Verse I.10. If Duryodhana were really so sure of his side’s superior might, surely he would not be so insistent on guarding Bhīṣma at all costs. At the very least, this suggests the brittleness of Kaurava morale and its tendency to shatter if its leaders are lost.

Vectors, sacrifices, zodiacs

Finally, one minor observation on the use of the word ayana in this verse. In the literal sense in which it is being used here, it simply means a “vector of attack”: It refers to a possible opening or vulnerability in a battle formation which might be exploited by the enemy. But the word also has two additional resonances that matter here:

The word ayana is often used in the context of Vedic ritual to refer to some sacrifices, usually large public sacrifices (sattras) like the Kuṇḍapāyinām Ayana and the Gavām Ayana. This echoes the understanding of the Mahābhārata war as a raṇa-yajña, a “war-sacrifice”. We are thus being told, in effect, that this greater war-sacrifice will include a number of smaller setpiece battle-sacrifices (just as a large sattra rite will include a number of smaller rites within it, whose outcomes could determine the outcome of the overall rite), and that Bhīṣma is expected to play a central role in many of these subordinate battle-sacrifices.

Especially in the context of protecting Bhīṣma’s life, the word ayana has special significance: Bhīṣma had earned a boon that meant that he could choose his own moment of death. When incapacitated and eliminated as a combatant by Arjuna, he chose to stay alive until the winter solstice, auspicious since the sun then begins its gradual northward movement across the sky for the next six months. This movement is known as the uttarâyaṇa “northern shift”. Thus, when Bhīṣma chose to depart, he picked his own ayana to move to the world of the gods.

The significance of Duryodhana’s speech

Why would the Gītā contain such a lengthy speech by Duryodhana right at the start? And why have we had to spend so much time pondering over his words? What relevance does it have for our lives today?

“Previously on the Gītā …”

To answer these questions, let us first recapitulate the arc of Duryodhana’s speech and behavior over these nine verses:

[Prior to verse I.2] Duryodhana begins by observing the Pāṇḍava forces. He is likely unnerved or discomfited by their arrangement.

[Verse I.3] He then takes out his frustration on his own preceptor Droṇa, all but accusing him of being a secret supporter of the Pāṇḍavas.

He goes on and on about the Pāṇḍava heroes [verses I.4–6], while lavishing a lot less praise on his own (arguably even better) generals [verses I.7–9].

[Verse I.10] His final assessment of the relative balance of power between the two sides is so ambiguous as to be entirely self-contradictory.

[Verse I.11] His closing lines, addressed to his generals, are extremely defensive-minded, bordering on defeatist.

Duryodhana’s vices

This arc, short though it is in the context of the greater story of the Mahābhārata, conveys some of the essential characteristics of Duryodhana: his envy, his covetousness, his resentment, and his fear. Like his father Dhṛtarāṣṭra, Duryodhana sees the world as Us and Them, and cannot rest until the Us rule over the Them. All through his life, Duryodhana has wanted to be numero uno, and has thus always struggled to gain the upper hand over his cousins the Pāṇḍavas. Unable to take delight in their success, he has let his jealousy consume him and allowed his paranoia to take over. Even at this stage in the war, when he enjoys every possible military advantage, he is still so conflicted that he cannot make a single clear statement about his chances of victory.

Duryodhana’s virtues

And yet, I’m going to claim that Duryodhana represents an improvement over his father, Dhṛtarāṣṭra, at least in the context of the Gītā. Duryodhana, for all his faults, has two virtues that his father lacks: first, he can see for himself; second, he is present in the arena as a participant.

Seeing reality for what it is

Now, I hasten to emphasize that I am not referring to Dhṛtarāṣṭra’s physical blindness here—it would be cruel and unfair to belittle him for a condition that afflicted him from birth. Rather, I’m talking about Dhṛtarāṣṭra’s psychological blindness here: his bias in favor of his own son and his inability to see the Pāṇḍavas fairly. By contrast, Duryodhana sees the Pāṇḍavas quite clearly: he knows they are “better” than he is. He sees reality in a way that his father cannot. To open one’s eyes and to see reality is the first step—even if it leaves us discomfited or angry!

“The man who is actually in the arena”

Duryodhana’s second virtue is that he is actually present on the field of action: he is ready and willing to fight for what he cares about. He may be fighting for the wrong things and he may be making a great strategic mistake, but he is at least willing to put himself in danger to achieve his goal.

To put it in the language of Nassim Nicholas Taleb, Duryodhana has skin in the game—quite literally. This again represents a step forward from the passivity of his father, as per the self-transformation program of the Gītā: it is, at the end of the day, a call to action.

From caricature to character

Duryodhana is thus a complex character filled with different, conflicting drives and motivations. It is tempting to flatten his portrayal by thinking of him as the villain of the Mahābhārata or as a personification of some form of evil, such as Envy or Greed. But to do so would be an injustice to him and to us, in my opinion; after all, we are seldom the villains of our own stories about ourselves!

It is better to take Duryodhana as a complex and contradictory character—aren’t we all?—and to learn from both his virtues and his vices. It is also helpful to see the world from Duryodhana’s perspective, even if briefly, because we are soon going to see the world from Arjuna’s eyes; the differences between the two are going to be extremely significant.

Expressed more metaphysically: We may start in darkness and inertia (tamas, to use the terminology of Sāṅkhya). To break out of this rut and to embark upon our self-transformation, we need a dose of passion, energy, and action (rajas). This is not the end-goal, nor is it something that is necessarily good in and of itself, But it can give us the impetus to escape from our psychological / moral / spiritual paralysis and slowly move towards a brighter, lighter (sattva) self.

|| Sarvaṃ Śrī-Kṛṣṇârpaṇam astu ||

When I turned to the Sanskrit supercommentaries on this verse after I wrote up these notes, I was delighted to note that both of these issues are noted and debated by different groups of commentators, and overwhelmed to see the sheer volume of commentary that has gone into explicating the meaning(s) of this one verse.

To use the proper Sanskrit terminology instead, the name bhīṣma is a vyāpaka (“pervader”) of the name bhīma, which correspondingly is a vyāpya (“pervadendum”) of the name bhīṣma.

As per Vararuci’s Ekâkṣara-nāma-mālā, a compendium of meanings of monosyllabic nouns in Sanskrit, we have:

bhīr bhayaṃ kathitaṃ budhaiḥ || (EĀNM 33d) maḥ Śivaś candramā vedhā(ḥ) | (EĀNM 34a)

Very elaborate and thought out writing.

Love the various meanings of words that give rise to different meanings of the slokas and yet all fit in.

Summary of all 10 verses is very beautifully written.

Superb.

🙏👍👍👍. 7*