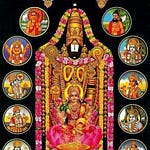

We are now exactly at the halfway mark in our journey through the Śrī Veṅkaṭeśa Suprabhātam: the 15th verse stands as the hinge between the first 14 and the final 14 verses. And quite appropriately, this verse is about the mountain peaks where Lord Veṅkaṭeśvara dwells.

Śrī-Śeṣaśaila-Garuḍâcala-Veṅkaṭâdri- Nārāyaṇâdri-Vṛṣabhâdri-Vṛṣâdri-mukhyām | ākhyāṃ tvadīya-vasater aniśaṃ vadanti Śrī-Veṅkaṭâcala-pate! tava suprabhātam || (VSu 15) श्रीशेषशैल-गरुडाऽचल-वेंकटाऽद्रि- नारायणाऽद्रि-वृषभाऽद्रि-वृषाऽद्रि-मुख्याम् । आख्यां त्वदीय-वसतेर् अनिशं वदन्ति श्रीवेङ्कटाचल-पते! तव सुप्रभातम् ॥

Śeṣa-mountain Garuḍa-mountain Veṅkaṭa-mountain Nārāyaṇa-mountain Vṛṣabha-mountain Vṛṣa-mountain: Such are the names of Your dwelling-place which people chant incessantly: O Lord of the sacred mountain wealth-weaving, sin-cleaving Venkatam, a blessed morning unto You!

This verse names six out of the seven hills of Tirupati, and points out that people are constantly chanting the names of these dwelling-places of Lord Śrīnivāsa and Padmāvatī Tāyār.

Now, it might seem a little strange to dwell so much, if you pardon the pun, upon the names of the hills on which the shrine of Tirupati is built. Why not just directly recite the name of the Lord Himself?

There is a general answer to this question that holds true for all dwelling-places of the Divine, and there is also a particular answer that is specific to Tirupati.

Where does the Lord dwell?

The general answer is that there is indeed something special about the dwelling-places of the Lord that warrant this kind of contemplation directed towards them. We can perhaps speak of an ex ante and ex post kind of holiness in these places.

Temples that house the Divine Presence are of course sanctified through numerous consecration rituals, both initially when the Divine Presence is invited to dwell in the sanctum, and periodically, through brahmôtsava rituals and so on. This gives them a level of holiness that is not typically present in other places. (If you’ve ever stepped into an ancient temple’s sanctum sanctorum, you will know that this “vibe” is particularly pronounced there.)

Furthermore, the continued Divine Presence (sānnidhyam) in these shrines continues to imbue their environment with a feeling of sanctity. This is the ex post view on why these locations are themselves worthy of reverence.But there is also an ex ante argument to be made, that asserts that these locations were special even before temples were erected there—because they were the sorts of places that would be made into temples. And even among temples, there are some that are regarded as particularly holy because the Divine Presence there was self-manifested (svayaṃbhū, or svayaṃ-vyakta), rather than having to be invited there by human ritual. The fact that the Divine chooses to manifest in some places rather than others clearly marks them off as special.

Celebrations of sacred places

Thus the very soil itself in places like Vṛndāvana is treated as holy, since the Blessed Lord Kṛṣṇa Himself walked those lands. Similarly, sacred hills like Hastigiri, atop which Lord Varadarāja of Kāñcīpuram dwells, are also celebrated: in fact, Swāmī Kūrattāḻvān opens his magnificent Varadarāja-Stava with 10 verses in the lilting Rathôddhatā meter praising the greatness of the hill.1

And as it so happens, this reverence for Divine dwelling-places is extended in the Śrīvaiṣṇava tradition to the birthplaces of the Saints and Sages of the tradition itself. Many benedictions recited either before or after the recitation of the Āḻvārs’ sacred compositions celebrate their birthplaces.2

The Divine Dwelling-place in Tirupati

But even by the standards of holy places sanctified by Divine self-manifestation, the hills of Tirupati are especially sacred. Such is the power and sanctity of Lord Śrīnivāsa that, to house His Divine Presence on earth, other aspects of the Divine themselves came down to manifest themselves as the hills of Tirupati.

One such aspect is Ādi-Śeṣa, the Cosmic Serpent representing Infinity, who is said to have manifested as one of the hills (Śeṣâdri or Śeṣâcala) of Tirupati. Swāmī Deśikar goes even further and says that the hills are themselves a manifestation, in solid form, of the infinite Compassion and Empathy (dayā or anukampā) of Lord Veṅkaṭeśvara. As he sings in the opening verse of his Dayā-Śatakam:

prapadye taṃ giriṃ prāyaḥ Śrīnivāsâ-anukampayā | ikṣu-sāra-sravantyê iva yan-mūrtyā śarkarāyitam || (DŚ 1)

I take refuge in those mountains of Tirupati whose form is crystallized like rock-candy from sugarcane juice from the Compassion of Lord Śrīnivāsa.

Such is Swāmī Deśikar’s devotion to the physical mountain itself, separate from the temple shrine and the temple icon of Lord Śrīnivāsa Himself, that he sings again in praise of the mountain itself, this time in Tamil, in his Adhikāra-saṅgraham:

Kaṇṇan-aḍi-yiṇai yĕmakku kāṭṭum vĕṟpu kaḍu-vinaiyar iru-vinaiyum kaḍiyum vĕṟpu tiṇṇam idu Vīḍ’ ĕnnat tigaḻum vĕṟpu tĕḷinda pĕrum tīrthaṅgaḷ śĕṟinda vĕṟpu puṇ(ṇi)yattin pugal id’ ĕnap pugaḻum vĕṟpu pŏn(n)-ulagil bhogam ĕllām puṇarkkum vĕṟpu viṇṇavarum maṇṇavarum virumbum vĕṟpu Vēṅkaṭa-vĕṟp’ ĕna viḷaṅgum Vēda-vĕṟpē! (AdhS 43)

The verse is quite difficult to translate due to its many layers of meanings, but its surface meaning is roughly as follows:

This is the Mountain where Lord Kṛṣṇa shows us His Two Feet; This is the Mountain which annihilates both kinds of deeds even those performed by the most dastardly; This is the Mountain which is surely our Heavenly Home manifest here; This is the Mountain which is overflowing with pellucid sacred tanks; This is the Mountain which is praised as being the repository of all virtues; This is the Mountain which connects us with the eternal felicities found in the Golden Heavenly Realm; This is the Mountain which is desired by the denizens of the terrestrial and the celestial spheres: This is the Veṅkaṭa Mountain which is resplendent as the Veda in mountain form!

Two secret, staggering implications

Deeper reflection on the sacredness of the Lord’s dwelling-places brings us to the heart of two sacred mysteries.

The Divine within

First, it is not just the case that the Divine dwells in temples (as the temple icon, arcâvatāra). The Divine also dwells within each of us, as our innermost self, as our Innermost Controller (antaryāmin). And since there can be no diminution of the sacredness of the Divine itself, this must necessarily mean that, ex ante, each of us bears an intrinsic sanctity that comes from each of us being a temple to the Divine. We may not satisfy the ex post condition of sanctity due to our thoughts, words and deeds, but our innermost selves are always and already sanctified by the Divine Presence in them. It is for us to live our lives out in recognition of this Divine in-dwelling that helps infuse sanctity and holiness into everything we do. (Seen in this light, the Saints and Sages are those who lived their lives in the light of this truth, and who thus shone with the Divine Presence.)

The Divine without

Second, it is not just us but the entire cosmos that is filled with the Divine Presence. In the words of Prahlāda being persecuted by his demonic dad, as sung by Nammāḻvār (Tiru-vāy-mŏḻi II.8 (Aṇaivadu).9):

yĕṅgum uḷan Kaṇṇan: “Kṛṣṇa of the beautiful eyes is omnipresent.”

The radical implication of this is that everything in the universe is a dwelling-place for the Divine!3 This in turn means everything is ex ante sanctified in its own way: everything radiates the aura of the Divine to those who have the eyes to see it. In this deepest of senses, it is no surprise that recalling the names of the dwelling-places of the Divine Couple leads us to Them.

|| Śrī-Padmāvatī-nāyikā-sameta-Śrī-Śrīnivāsa-parabrahmaṇe namaḥ ||

For instance, in verse 5, Swāmī Kūrattāḻvān sings directly of the hill itself:

Yaṃ parôkṣam upadeśatas Trayī «nêti, nêti» para-paryudāsataḥ | vakti yas Tam aparôkṣam īkṣayaty eṣa taṃ Kari-giriṃ samāśraye ||

I take refuge in this very Elephant Hill which makes Him perceptible: Him, whom the Triple Vedas declare to be imperceptible, saying "He is not this, not this" to exclude any confusion of Him with others.

Where the Vedas have an abstract and philosophical perspective on the Divine, the sacred hill of Hastigiri makes the Lord concrete, perceptible, and approachable.

For example, a benediction to Tŏṇḍar-aḍip-pŏḍi Āḻvār recited before his works, beginning Maṇḍaṅguḍi, is in celebration of his birthplace of Tiru-maṇḍaṅguḍi. And another famous example, the holy town of Śrī-villi-puttūr, home to Pĕriyāḻvār and his daughter Āṇḍāḷ, is celebrated in the benediction Kōdai piṟanda ūr, recited upon the completion of the recitation of Āṇḍāḷ’s Tirup-pāvai.

I was amazed to hear exactly this idea expressed by the scholar of Judaism, Daniel Matt, in a YouTube lecture on the magnificent mediaeval mystical text, The Zohar. Prof. Matt read out a quote that has imprinted itself in my memory even though I know no Hebrew: ein maḳom ba-aretz panui min ha-Shekhinah (אין מקום בארץ פנוי מן השכינה): “There is no place on earth that is empty of the Divine Presence.”

Share this post