Sāṅkhya from the inside out

A brief introduction to the philosophical framework underlying the Gītā

This post was written as a companion to my other post

but it is in fact self-standing and can be read independently. The two posts can be read in either order.

An unconventional introduction to Sāṅkhya

If there is an underlying philosophical framework for the Śrīmad-Bhagavad-Gītā, it would be Sāṅkhya. Regarded as one of the Six Darśanas, “perspectives, theories” of Hindu philosophy, Sāṅkhya provides a conceptual vocabulary, especially around metaphysics, for virtually all of the religious traditions of India.1

It is therefore extremely important for any serious seeker to come to terms with the Sāṅkhya perspective on reality, to grapple with its categories, and to understand how and why such a worldview may make sense.

I have written briefly about the Sāṅkhya framework in the context of the Gītā, but in this post, I want to do something a bit different: I will provide an inside-out introduction to the Sāṅkhya framework that tries to make sense of the different categories on their own terms.

A quick note: This is quite a long post and is not meant to be read in a single sitting; it is meant to be re-read, ruminated upon, and digested. I’ve broken it up into easy-to-swallow morsels, indicated by the divider lines.

A quick meditation

Take a deep breath, then pick some object in front of you, and direct your full attention to it for 10–15 seconds. What do you experience, with all your senses? How are you engaging with it? What other thoughts come up about this object in this short span of time? Then take another deep breath, and reflect on your experience of meditating on that object. If you like, you can write down your thoughts before you read further.

In my case, I have by my side a mug half-full of hot South Indian coffee, covered with a lid. What do I notice when I contemplate this mug?

Most obvious is the mug itself. It’s made of some sort of ceramic (essentially a lump of clay shaped and heated), which has then been painted with some colors in a certain pattern.

The mug contains the coffee, which is of course a liquid. The coffee is hot to touch, colored sepia, and it has a delicious aroma to it. When I drink my coffee, it tastes slightly bitter to me.

Since the coffee is hot and the room is cold and unheated, I can see steam rising from the cup. This vapor has condensed on the underside of the lid, so I blow on the lid to dry it off.

The mug is only half-full—of coffee, that is. The other half looks entirely empty to me (though of course science tells me that it’s actually full of air). Then again, it’s also because I remember that the mug used to contain more coffee (before I drank it).

The mug is quiet when at rest, but I remember that, when I was boiling the water to make the coffee, the bubbling boiling water made a distinct gurgling noise (as the bubbles popped) that itself was very relaxing.

And all of this from a 15-second meditation upon a mug of coffee!

Making sense of experience

There are different ways to “interpret” our experiences, as we focus on different aspects. A Theravada Buddhist would interpret and explain this same meditation very differently than a Kevalâdvaita Vedāntin. Let us now try to make sense of it the way Sāṅkhya might do so. I will obviously use my coffee meditation as the raw material for this reflection; you should try this with your own experience.

The objects of experience

Let’s start with the object, or content (viṣaya), of experience: my mug half-full of steaming coffee in this case. As far as Sāṅkhya is concerned, the coffee mug does in fact exist; it is not an illusion (māyā). But at the same time, Sāṅkhya does want us to move away from a naïve understanding of the physical world as we happen to perceive it.

From physicality to processes

Now, I should emphasize, we have an excellent grasp of physical, material reality today—we call that discipline physics. When we compare that understanding to Sāṅkhya’s statement that the world is made up of 5 “gross elements” (bhūtas), the latter ends up seeming quite inadequate. But that is not actually what Sāṅkhya is concerned with.

Instead, Sāṅkhya cares more about the human experience of reality, and all of a sudden it no longer quite matters what physics tells us. For Sāṅkhya, the 5 gross elements are not necessarily to be thought of as “elements” like hydrogen or sodium or iron or uranium; they are processes, they are tendencies. To assess Sāṅkhya’s claims as if it were pre-modern natural science would be to make a category mistake.

Thus, when Sāṅkhya says my coffee mug is made of the earth element, what it is really referring to is the fact that I experience that particular configuration of reality as having solidity, as a process of supporting or containing. This process is opposed by the process of being contained which holds true for the water element, that is to say, liquidity. This water element also shows a tendency to moisten which is then opposed by the tendency to dry that is exhibited by the air element; and so continue the mutually opposing and reinforcing pairs of processes that establish a dynamic equilibrium. Sāṅkhya thus forces us to re-see the world of seemingly solid objects as dynamic and mutually balancing processes made up of subprocesses and so on further.

The qualia of experience

But this is only the start of the process. As we continue to interrogate our experience of reality, we realize that we seldom, if ever, directly encounter things as such (vastu in Sanskrit, or Ding an sich in German). Instead, we experience qualia: colors, odors, flavors, and so on. The coffee looks a certain way to me; it tastes and smells a certain way; it feels a certain way in my tongue; and so on. I experience it as a bundle of dynamic colors, flavors, and odors.

Whether or not there is in fact an underlying substance that acts as the physical substrate for these various qualia is irrelevant to Sāṅkhya.2 Sāṅkhya, as always, is concerned with our experience of reality: it therefore draws our attention towards organizing and classifying these qualia into different buckets.

We might start by noticing the different colors we see, then the different kinds of sounds we hear, or the various tastes we enjoy, and so on. This process of gradual classification and abstraction eventually brings us (says Sāṅkhya) to the 5 “subtle elements” (tan-mātras), the qualia as such that we experience and that we interpret as giving rise to physicality.

Thus, for Sāṅkhya, the 5 tan-mātras give rise to the 5 bhūtas (the 5 “gross elements” discussed above) because the former are more basic in our experience than the latter.3

Sarga and prati-sarga

This is our first encounter with a new kind of process, which in Sāṅkhya is called sarga. Whereas the processes we saw earlier were about different kinds of gross matter reorganizing themselves, the sarga that generates a bhūta from one or more tan-mātras is a metaphysical condensation from a more subtle level of reality to a less subtle level. (The reversal of this, resulting in an involution into a more subtle and less differentiated level, is called pratisarga.) We will soon see further cases of this kind of differentiation and condensation.

The means of experience

Let us turn now from the “what” of our experiences to the “how”: How do we experience objects? How do we interact with them? Our capacities to do so are known as the indriyas in Sāṅkhya, and we will soon encounter 11 of them.

From sense-organs to processes of sensing

If there are 5 types of qualia as such (tan-mātras) which we experience, it stands to reason that we must correspondingly have 5 types of senses. Indeed this is what we teach even toddlers today, that we have 5 senses.

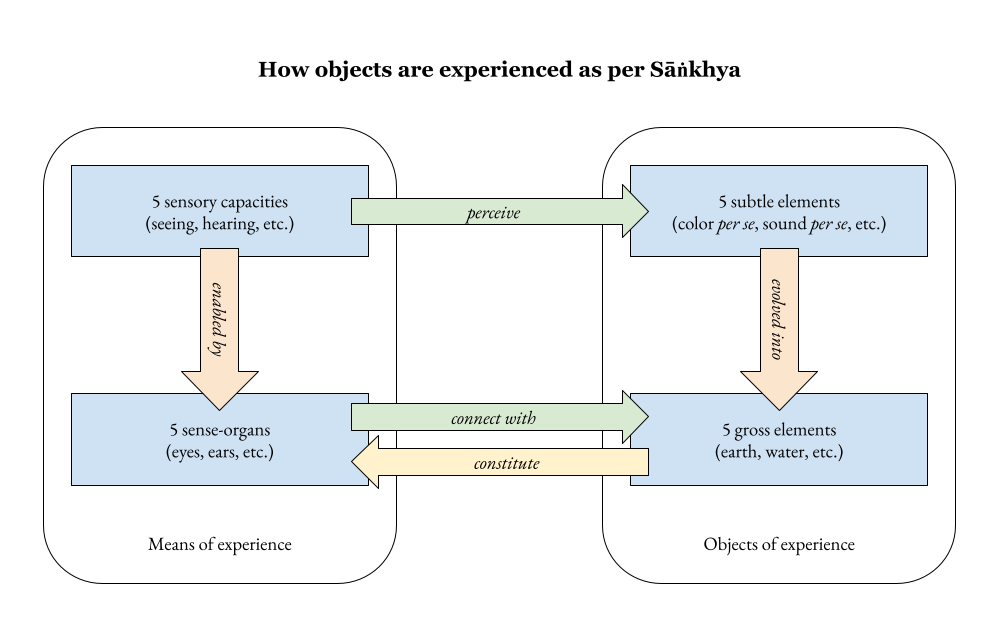

However, there is one subtlety here: We often tell little children, and we occasionally fall into this trap ourselves, that our 5 senses are our eyes, ears, and so on. But this can’t be right! These are really our sense-organs: they are physical objects/processes made up of the same 5 “gross elements” as the objects they are supposedly experiencing. The 5 sense, or sensory capacities (buddhîndriyas), are in fact the processes of seeing, hearing and so on, which take as inputs the 5 tan-mātras. The physical sense-organs, which may have to be supplemented by reading glasses or hearing aids, are simply the enablers of these sensory processes. A nice commutative diagram may help clarify the issue:

From action-organs to processes of interaction

Where the buddhîndriyas act as sources of input for our experience, the karmêndriyas, or “actional capacities”, are our outputs onto experience: they help us interact with and reshape our objects of experience. After all, I need to be able to hold my cup of coffee and drink it and exclaim my delight upon tasting it!

Sāṅkhya posits 5 actional capacities: speaking, grasping, moving, excreting, and reproducing. As we saw above, these five capacities should be understood as processes, and should not be confused with the physical organs that enable them (such as our hands and legs).

The mental integration / construction of experience

Things might be looking hunky-dory so far, but in fact we are facing two difficult problems at this point with our meditation exercise:

As of now, our five different senses allow us to sense five different types of qualia. But we don’t actually experience the world that way: I don’t experience my coffee as a patch of brown and a dash of bitterness and a whiff of heaven. The key word there is as. We experience things as integrated wholes (even if they are not—this is what happens in optical illusions).

But this integration cannot be performed by any of the sensory capacities themselves. What, then, integrates our sensory inputs into a single seamless experience?The coffee mug exercise had another limit: we were looking at a physical object external to our senses by exercising our external sensory capacities (bāhyêndriyas or bāhya-karaṇa). But we know we can also work with purely mental objects as well, such as the memory of a coffee mug, the fantasy of The Shire, or the abstraction of the homology groups of a torus.4 What allows us to perceive these purely mental objects?

Sāṅkhya posits that these two problems are actually interconnected: External inputs must be absorbed into a form that allows our minds and imaginations to work with them, just as reading a story gives rise to internal forms that can be worked with and reshaped. In fact, our experiences of the world are never purely perceptions of the external world (isn’t that why people practice mindfulness!); even as I pick up my mug to sip my coffee, I am already anticipating—imagining the future—what it will taste like, based on my remembrances of coffees past. Our solution to the first problem will therefore need to work with mental inputs as well.

Sāṅkhya thus posits a single, two-sided solution to both of these problems: There must be a mental process, manas, that is able to function both as a mental sensing process (to perceive and absorb mental inputs) as well as a mental actional process (to reshape and to integrate these mental inputs to produce our seamless experience of reality).

Injecting a sense of self: the ego (ahaṅkāra)

We have by now established a complex, interconnected network of tattvas to account for our experiences. However, there still remain a few key words in my description of the coffee mug that we have not yet accounted for: “I”, “me”, “my”. This sense of ego seems to be built into our experiences; it is not like as if we perceive it separately in the external world. Where does our ego come from?

Sāṅkhya solves this problem by positing a new entity: the ahaṅkāra, literally the “I-maker”, sometimes (inadequately) translated as “ego”. The operation of the ahaṅkāra is responsible for the construction, injection, and recognition of individuality in experience. This is not just arrogance or egotism in its negative senses (which would correspond to the casual use of ahaṅkār in modern Hindi). Every time we experience a sense of “I”-ness or “my”-ness, even in situations where it would be quite normal to do so, Sāṅkhya claims that we are really experiencing ahaṅkāra in operation.

For me personally, this operation of ahaṅkāra shows up most transparently when I try to empty my mind and meditate. Within a couple of seconds, I inevitably end up wandering down some mental track that begins with I wonder if … and ends only when I (ahaṅkāra again!) notice this train of thought and try to restrain it.

For Sāṅkhya, this constantly-operating process of individuality is the unifying background of our experience. This is obviously true when I experience such states as This is my coffee mug or I am drinking coffee; however, it is also true even in the case of seemingly neutral experiences like This coffee smells good!. The experience is really This coffee smells good [to me]!

Because it is ahaṅkāra that is the common thread uniting both the objects and the means of our experience (including the manas), Sāṅkhya argues that it is ahaṅkāra itself that in fact evolves into both the 5 subtle elements and the 11 capacities, via the same process of sarga that we have already seen before.5 The thoughtless differentiation of ahaṅkāra into objects and means of experience can conceal its behind-the-scenes role in constructing our field of experience. It takes serious analysis and self-reflection to pass beyond our usual thoughtlessness and to come to pure ahaṅkāra.

“Self”-less discrimination (buddhi)

Ahaṅkāra is where Descartes grounded his philosophical rumination, giving rise to his (in)famous cogito ergo sum. But Sāṅkhya continues to dig deeper: Is this sense of individuality real? It certainly does not seem stable or unchanging. How can it be the stable ground of genuine reflection?

It takes hard work to get to this next step, but it is possible through practice to penetrate through the veil of the ego to get to impersonal judgment. When we take our ego out of the equation, we can boil our experience down to the most basic judgments, “X is Y” and “X is not Y”.

These equations are meant to be objective, since we have eliminated the subjective component (ahaṅkāra) from them. They thus include what we might think of as factual or mathematical knowledge (jñāna), like 1 + 1 = 2. But they can include religious/ethical/legal judgments (dharma) as well. And they can even include imaginative contemplative exercises as well which should yield the same result for everybody; for instance, visualizing the structure of the solar system or the sacred corporeal form (vigraha) of a deity.

This capacity for judgment, for categorizing X as Y and for differentiating X from not-X, is known as adhyavasāya in the Sāṅkhya framework, and is the hallmark of the highest level of differentiated human experience, which is known as buddhi.

The unified “mind”

In practice, the operations of buddhi, ahaṅkāra and manas are tightly intertwined and are difficult to disentangle. They are therefore sometimes treated as a single unit, the antaḥkaraṇa “internal instrument”, which is perhaps the closest word in the Sāṅkhya system to the way we use the word “mind” these days.

The antaḥkaraṇa unifies all human cognitive activity: perception, ego, judgment, self-awareness, and self-reflection.

Beyond discrimination: unmanifest nature (mūla-prakṛti)

Sāṅkhya would be a powerful and coherent framework for describing human experience even if it stopped at the level of buddhi. And indeed this is as far as we can go in terms of human perception. But the Sāṅkhya framework continues to dig deeper still, based on a powerful insight: Even buddhi tends to differentiate entities from one another. What happens if we unify the X and the Y that go into an experience?

As the Sāṅkhya-kārikā puts it, all of manifest, differentiated experience shares some common properties:

(1) hetumad, (2) anityam, (3) avyāpi, (4) sa-kriyam, (5) anêkam, (6) āśritaṃ, (7) liṅgam | (8) sâvayavaṃ, (9) para-tantraṃ: Vyaktaṃ; viparītam: Avyaktam ||

The Manifest is: (1) an effect of some cause, (2) temporally limited, (3) spatially limited, (4) dynamic, (5) multitudinous, (6) superimposed, (7) indexical, (8) composite, and (9) subordinate. The Unmanifest is the opposite of all this.

All of these properties hold true of our experiences in some form or the other. All of these properties suggest that our experiences are transient, temporary, and limited. As a result, if we are looking for a stable, permanent ground for reality, buddhi cannot be it.6

By definition, though, we cannot directly experience this stable ground (for any experience of it will be, like all other experiences, fleeting). Sāṅkhya argues, however, that we can infer our way to the stable ground based on logic and reasoning. The opposite of these properties allows us to get to mūla-prakṛti, the unmanifest, undifferentiated (avyakta) substrate of all experience.

In its undifferentiated stillness, mūla-prakṛti is calm and unmoving, its three constituent threads (guṇas) in a perfect, meta-stable equilibrium. (For fear of making this post even longer, I will resist the temptation to get too deep into the three guṇas for now.) When disturbed, mūla-prakṛti begins to differentiate as its guṇas, perturbed, begin to interact with one another in highly non-linear ways to create the variegated reality of our experience.

Sāṅkhya explains this through a series of metaphors:

Mūla-prakṛti, undifferentiated and unmanifest, is like the deep ocean, while manifest experience is like the differentiated waves on the ocean’s surface with their varying crests and troughs.

Mūla-prakṛti, undifferentiated and unmanifest, is like a lump of pure gold, while manifest experience is like the different objects that can be fashioned from that gold by melting and reshaping it (first a statuette, then a bowl, then a brick, and so on).

It is this potential for transformation, for spiritual alchemy if you will, which has made the Sāṅkhya metaphysical framework so useful for so many different philosophical traditions in India.

Beyond all observables: the pure observer (puruṣa = draṣṭṛ)

We are almost at the end of our tour of Sāṅkhya. We have just a few more questions to answer:

What disturbs or interacts with mūla-prakṛti, originally still and undifferentiated, in order to trigger its differentiation into manifest experience?

What, or who, is the true experiencer of experience, the true seer, the pure observer (draṣṭṛ)?

Notice that the answer to these questions cannot be a further abstract of mūla-prakṛti in any way, because mūla-prakṛti has been defined in a way that blocks this move. And again by definition, the answer to these questions cannot itself be directly experienced (for then it would have to be an evolute of mūla-prakṛti again).

For Sāṅkhya, the single answer to both of these questions is the final element of the framework: the puruṣa, our innermost self, which is able to observe without interacting.7

Puruṣa is the pebble tossed into the pond of prakṛti that sets off its ripples; it is the true experiencer (bhoktṛ) of the myriad experiences (bhoga) that are all the dance of prakṛti. It is the unobservable observer who remains once everything else is peeled away.

Here culminates the great dualist metaphysics of Sāṅkhya: everything we are, everything we experience, is simply the interaction of puruṣa and prakṛti. It is no exaggeration to claim that a substantial part of the Hindu religio-philosophical enterprise over the last two millennia (and beyond) has been dedicated to exploring the ramifications of the puruṣa–prakṛti interaction in every sphere of human experience, and to uncovering and perfecting techniques for restoring this primordial equilibrium.

Appendix: sarga and pratisarga revisited

Now that we have the whole Sāṅkhya system in mind, let us return to the metaphysical evolution (sarga) that we touched upon earlier. The distortions and fluctuations of mūla-prakṛti result in its progressive differentiation and condensation, or sarga. The soteriological goal of Sāṅkhya as a philosophical school is to reverse this differentiation and to return to equilibrium. This reversal or involution is known as pratisarga.

The Sāṅkhya framework sets up a complex sequence of differentiation, in which different elements starting with mūla-prakṛti evolve into other elements. In any such transformation, the less differentiated starting point is known as a prakṛti “evolvent”, while the more differentiated element is known as a vikṛti “evolute”. In a famous verse in the Sāṅkhya-kārikā, the 25 elements of Sāṅkhya are classified into four classes based on their position in this sequence:

mūla-prakṛtir avikṛtir, mahad-ādyāḥ prakṛti-vikṛtayaḥ sapta | ṣoḍaśakas tu vikāro, na prakṛtir na vikṛtiḥ puruṣaḥ ||

Mūla-prakṛti is evolvent alone and not an evolute. The seven elements starting with mahad are both evolutes (of the previous element) and evolvents (of the succeeding element). There are sixteen elements that are only evolutes. And puruṣa is neither evolvent nor evolute.

If we depict Sāṅkhya evolution using directed graphs,8 this results in a very neat classification:

Mūla-prakṛti has an outgoing arrow but no incoming arrows.

The next seven elements have both incoming and outgoing arrows.

The final sixteen elements have only incoming arrows and no outgoing arrows.

Finally puruṣa, which does not play the game of evolution–involution, has neither outgoing nor incoming arrows.

From a purely philosophical perspective, the Nyāya-Vaiśeṣika text-tradition is undoubtedly more rigorous, but it is also therefore less accessible to individuals.

Some schools of Buddhism will at this point dissolve objects into just these elements, and thus deny their existence; however, Sāṅkhya does not do that and indeed may not actually agree with that view at all.

This is fundamentally different from the Nyāya-Vaiśeṣika worldview (or the Aristotelian one), in which substances are more basic than their properties.

If that sounds like incomprehensible abstract nonsense, it’s meant to be! Modern mathematics works with highly abstract entities that can be represented in various ways. The details of this stuff are not relevant to my point here; just the fact that we are able to discuss and argue and marvel over such abstract entities

Note that the standard phrasing of this evolution suggests that “ego” transforms into eyes and ears and the like on the one hand and earth and water and the like on the other. This, of course, makes no sense and makes Sāṅkhya sound ridiculous. I hope that my account is both more persuasive and more sympathetic to Sāṅkhya.

On the other hand, for Buddhist schools that accept the momentariness (kṣaṇikatva) of fleeting experiences and which regard the pursuit of permanence as a mistake, this would be a good place to stop the investigation.

While mūla-prakṛti is emphatically just one, the question of just how many puruṣas there are remains a point of debate in Sāṅkhya. In the classical formulation of Sāṅkhya as per Īśvarakṛṣṇa, there are innumerable puruṣas, all qualitatively identical but numerically distinct, reflecting the fact that different observers do not and cannot share the exact same experience of reality. The worldview of the Upaniṣads and of Vedânta (and even earlier, as seen in the Puruṣa-sūkta) instead pushes for a single puruṣa, or perhaps a supreme Cosmic Puruṣa from which come other puruṣas.

I was inspired to think in these terms by Ch. 3 “The algebraic basis of metaphysics” of Jonardon Ganeri’s excellent Philosophy in Classical India: An Introduction and Analysis, which is a unique overview of Indian philosophy in rigorous analytical philosophical terms.

Wow. Superb post. I have read it 5 times. Still needs more readings. 😊👍🙌🙏❤️