Ch. 1, Verses 4–9, Part 2: A speculative interpretation

With a brief introduction to the Sāṅkhya philosophical framework

On this holy day of Śrī Rāma Navamī, I’m going to resume the thread of posting my commentary on the verses of the Śrīmad-Bhagavad-Gītā. I was supposed to do this over a month ago, but between crafting this post and its twin, things took me a lot longer than expected! Still, I hope the content makes up for it!

A while back, we saw Part I of my commentary on verses I.4–9

of the Śrīmad-Bhagavad-Gītā. We will now look at Part II of my commentary on these verses.

Part II: Philosophical speculations

I recognize that not everybody will find what I say in Part II totally convincing. That is totally fine by me! As I said in the introduction to this project,

my twin goals for this project are svīkāra and viniyoga: making the Gītā one’s own and applying it to one’s situation. For each of us, this will ultimately require a synthesis of our interpretation of the Gītā on the one hand with our personal background knowledge and beliefs; sometimes the first will dominate, and at other times the second will.

A suggested interpretation

Without further ado, here’s my more speculative interpretation:

These lists of names in Duryodhana’s speech are intended to suggest the philosophical framework of the Sāṅkhya school (or darśana) of Hindu philosophy.

The starting point for my claim is the fact that the total number of names—18 Pāṇḍavas and 7 Kauravas—add up to 25, which is famously the exact number of tattvas “fundamental constituents of reality” that the Sāṅkhya system enumerates.

Even more convincingly, it is possible to map different groups of names to different groups of Sāṅkhya tattvas as well. That is, the internal structure of the Sāṅkhya framework is mirrored—non-trivially, and in multiple overlapping ways—by the ordering and grouping of the 25 names.

Finally, as if to nail the importance of the number 25, we will soon see exactly seven more names added to the Pāṇḍava side, so that they come to enumerate the 25 Sāṅkhya tattvas just on their own. This then creates its own mapping between the groups of names and the groups of tattvas.

Why Sāṅkhya?

Of course, to construct a mapping, we will first have to take a(n abbreviated!) tour of the Sāṅkhya system. But even before we do that, we should ask ourselves: why would the Gītā want us to think about Sāṅkhya at this point?

Sāṅkhya categories and structures are pervasive throughout the Gītā and also in other sections of the Mahābhārata as well. Many of the arguments of the Gītā either set up or presume the Sāṅkhya framework. Furthermore, many of the characters of the Gītā can also be thought of as personifications of different elements of Sāṅkhya. Indeed, one of the great achievements of the Gītā is its synthesis of three strands of Hinduism: the Sāṅkhya framework, the Upaniṣadic message, and bhakti “devotion”.

Thus, encoding the Sāṅkhya framework at this early stage in the Gītā is a gesture towards what will be explored in greater detail in later chapters of the text. It is a hint for the careful reader that the tattvas of Sāṅkhya should be kept in mind while exploring the various relations

A whirlwind tour of Sāṅkhya

There are a great many debates about how best to understand Sāṅkhya. For now, I am going to focus on a psychological interpretation of Sāṅkhya; that is, I will describe and apply Sāṅkhya’s elements in the context of the human experience of reality.

Warning: This material is dense, complicated, and potentially confusing upon first reading. I encourage you to read and re-read it slowly. And not to fear, we will keep returning to it as we go through the Gītā.

As a companion to this post, I have also written up a rather different, and rather more detailed, introduction to Sāṅkhya

that goes into greater detail about the elements and that can be used as a guide to Sāṅkhya-style introspection.

Sāṅkhya dualism

Sāṅkhya is dualist: it postulates two distinct and independent fundamental constituents: puruṣa “self” and (mūla-)prakṛti “root-nature”.

Puruṣa is consciousness: It is the necessary background awareness that underlies all experience, it is the unobservable observer (draṣṭṛ) who sees all without being seen.

Mūla-prakrti is the raw material out of which everything we experience—both physical as well as mental—is constructed.1

The three guṇas

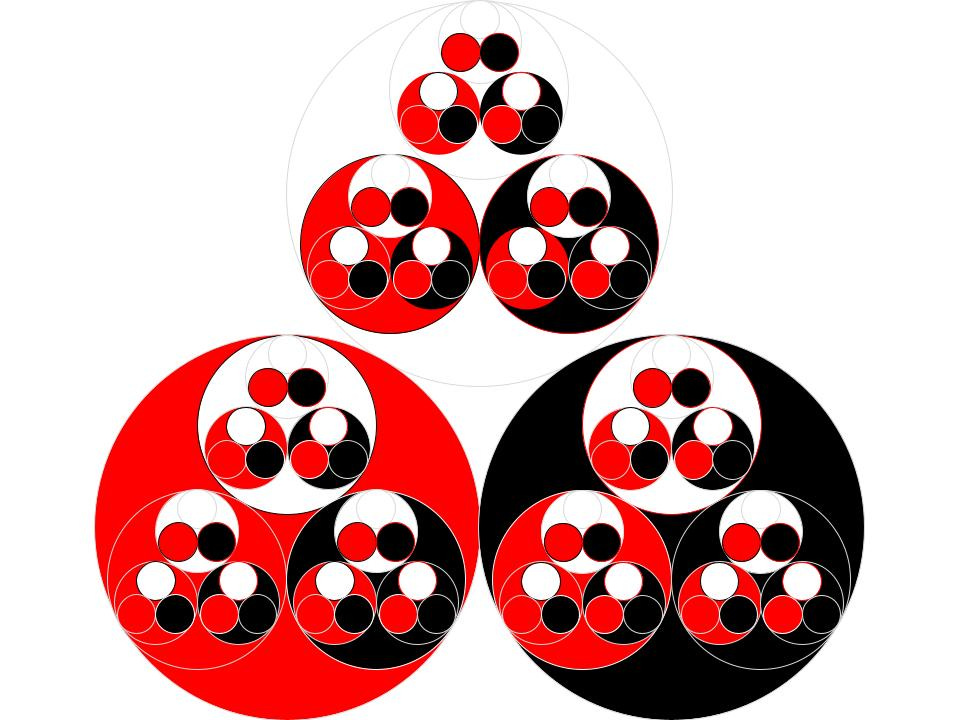

If mūla-prakṛti is the fabric of experience, then the threads which interweave to yield the specific contents of experience are known as the three guṇas, named sattva, rajas, and tamas.

Sattva is light, white, floating stillness, illumination, and hence goodness.

Rajas is red, movement, energy, and hence passion.

Tamas is black, inertia, darkness, heaviness, and hence depression.

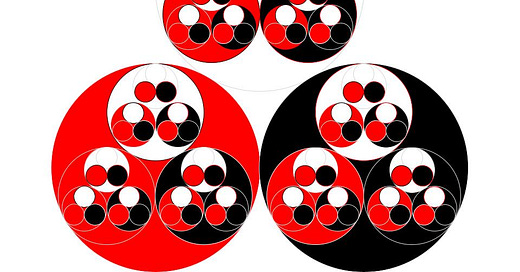

The three guṇas interweave and interpenetrate one another to generate everything that we experience. Borrowing an image of the 3-adic numbers from mathematics, I like to think of them in this fashion:

When the three guṇas are in perfect balance, mūla-prakṛti is in equilibrium and thus undifferentiated. But in the presence of puruṣa, the fabric of experience distorts and contorts, with ripples propagating through the guṇas to create a dance of prakṛti all around puruṣa.

Waves of the same sea

Imbalances in the guṇas differentiate mūla-prakṛti into a sequence of 23 elements, each contributing to a different aspect of experience. 7 of these elements themselves generate further elements; the remaining 16 do not evolve further but combine and interact with one another.

From mūla-prakṛti first comes buddhi “intellect”, which is the capacity to make determinative judgments of the sort “this is red” and “that is hot”. Buddhi thus judges, categorizes and classifies the contents of our experience.

From buddhi comes ahaṅkāra “ego”, literally the “I-maker”. This is the capacity for recognition and injection of individuality into experience. Cognitions of the sort “I’m seeing something red” or “I’m rich” all result in this construction of an “I” around the anonymous puruṣa. According to Sāṅkhya, this constructed self of individuality is in fact a distraction from the true, still, imperceptible, imperturbable self.2

From ahaṅkāra emerge all of the other evolutes, but in two different sets:

One set of 5 consists of the tanmātras “subtle elements”. These make up the qualia of o ur experiences: sounds, touches, colors, flavors, and odors.

The 5 tanmātras then further condense into the five bhūtas “gross elements”, which constitute the physicality of our experience. Their Sanskrit names translate to “space”, “air”, “fire”, “water”, and “earth”, but they are better thought of as emptiness, gaseousness, luminosity / exothermicity, liquidity, and solidity instead.

The second set of 11 constitute the human capacities to grasp different aspects of experience, to interact with experience, and to integrate them.

One set of 5, consisting of the buddhîndriyas “sensory capacities”, corresponds to what we think of as the 5 senses: hearing, touching, seeing, tasting, and smelling. Each of these is associated with the usual physical sense-organ (ears, skin, eyes, tongue, and nose, respectively), and is sometimes called by that name, but is technically distinct from it.

Another set of 5, consisting of the karmêndriyas “actional capacities”, captures different ways in which we interact with objects of experience: speaking, grasping, moving, excreting, and reproducing. Each of these is associated with a bodily organ (mouth, hands, legs, excretory organs, reproductive organs), and is sometimes called by that name, but is technically distinct from it.

Finally, we get the manas “mental organ”, sometimes incorrectly called “mind”, which acts both as a buddhîndriya and a karmêndriya:

In its receptive, sensorial mode, the manas takes in purely mental sensations (for instance, the content of our dreams) as well as the mental elements of physical sensation.

In its expressive, actional mode, the manas constructs and synthesizes a unified field of experience out of all the disparate inputs it receives.

Applying Sāṅkhya to the Gītā so far

Now that we have a quick and crude sketch of the Sāṅkhya system, we can begin to identify common patterns in the Gītā which mirror the structures and relations of the Sāṅkhya system. As we dive into later chapters of the Gītā, we will see how central these ideas are to the core message of the text.

Sāṅkhya and Duryodhana’s speech

After long reflection, I came up with two different ways to map the 25 warriors named by Duryodhana to the 25 tattvas of the Sāṅkhya framework. I will share both here and let you decide which one appeals more to you—or if you would prefer a different mapping of your own!

The first mapping

The first mapping focuses on the sizes of different groups of heroes:

The 7 Kaurava heroes map onto the first 7 evolutes of mūla-prakṛti.

The 11 Pāṇḍava heroes who are not biologically Pāṇḍavas (from Yuyudhāna to Uttamaujas) map to the set of 11 human capacities.

The 5 Draupadeyas map to the 5 bhūtas, which do not evolve any further. (Just like the Draupadeyas who all die without offspring.)

Abhimanyu Saubhadra can then map onto mūla-prakṛti, for it is through his son Parikṣit that the dynasty of the Kurus will be perpetuated.

That leaves Dhṛṣṭadyumna for puruṣa.

The second mapping

The second, more complex, mapping factors in number patterns as well as other characteristics of the heroes as follows:

Droṇa stands for puruṣa: he observes and receives Duryodhana’s speech, but we do not observe him directly at all.

Bhīṣma stands for mūla-prakṛti. This is partly ironical, because whereas mūla-prakṛti is the feminine “procreatrix”, Bhīṣma is famously celibate. But in a way, Bhīṣma is the root-cause of the Mahābhārata conflict due to his various choices and decisions, and thus Bhīṣma pitāmaha “grandfather” can map to mūla-prakṛti.

The five remaining Kauravas map to the five bhūtas, for they are dominated by tamas (moral darkness and physical concreteness, respectively).

As above, the 11 Pāṇḍava heroes who are not biologically Pāṇḍavas (from Yuyudhāna to Uttamaujas) map to the set of 11 human capacities.

The 5 Draupadeyas map to the 5 tanmātras.

Dhṛṣṭadyumna maps to buddhi, for we have already seen him described as dhīmat, being radiantly intelligent and perceptive.

Finally Abhimanyu Saubhadra maps to ahaṅkāra. One of the synonyms for the term ahaṅkāra is abhimāna, which closely resembles Abhimanyu’s name. More interestingly, the tragedy of Abhimanyu’s story is built around his fatal flaw (hamartia) of ego: his overconfidence and ego lead him into a heroic but tragic last stand against all the Kauravas, in one of the most powerful and heartbreaking scenes of the Mahābhārata war.

Sāṅkhya and speaking parts in the Gītā

We have seen three speaking parts in the Gītā so far—Dhṛtarāṣṭra, Sañjaya, and Duryodhana—and it is honestly quite shocking to me to see how well they map onto the three guṇas:

Dhṛtarāṣṭra corresponds to tamas in his passivity and his blindness (again, I emphasize, in the metaphorical sense only).

Duryodhana is rajas personified: action, passion, anger, exuberance, and movement.

Sañjaya is sattva: he shares information, casts lights, and clarifies—but he too is also passive and removed from the scene of the action.

Of course, we will see two more speaking parts in the Gītā! When we finally get to Arjuna, we will see his whole progression, from rajas to tamas to, eventually, sattva infused with rajas. Arjuna thus represents all of prakṛti in its dance and its movement towards equilibrium.

And of course, all of this is due to Kṛṣṇa, who isn’t merely a “representation” of puruṣa; He is Puruṣa Himself, the Supreme Person.

|| Sarvaṃ Śrī-Kṛṣṇârpaṇam astu ||

Sāṅkhya dualism is thus very different from Cartesian dualism, which is the standard dualism commonly known in the West. Cartesian dualism distinguishes between mind and matter, whereas for Sāṅkhya, mind and matter are both generated from mūla-prakṛti. Many of the common problems with Cartesian dualism, such as the debates on how mind and matter interact, are thus not an issue in Sāṅkhya dualism.

From the Sāṅkhya perspective, Descartes didn’t dig deep enough when he got to his famous cogito ergo sum “I think, therefore I am”: Descartes only got to the level of ahaṅkāra. He didn’t dig deeper to the level of buddhi (which would have simply been “this is a thought”), let alone the underlying imperceptibles of prakṛti and puruṣa.